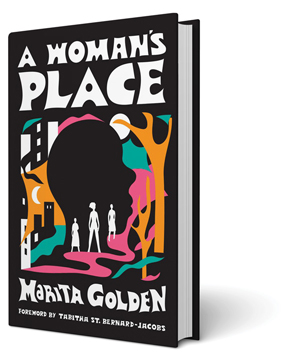

The opening scenes of A Woman’s Place feature three young Black women at a predominantly White university discovering the influences that shape their lives: Serena takes up activism on an international scale, Crystal embraces poetry as her medium, and Aisha focuses on faith and family. Their long-standing friendship acts as a balm for the challenges they encounter in the workplace and in their relationships. Originally published in 1986, the novel has been reissued as part of McSweeney’s Of the Diaspora series. Author Marita Golden, CAS/BA ’72, looks back on her early work with pride and reflects on the changes Black women have faced—and those they have created—in the intervening years.

What was it like to revisit your first novel with a twenty-first century perspective?

I was gratified to know that it still stands. I did a presentation at Busboys and Poets [in DC] with Sarah Trembath, a lecturer at AU, and two female African American students, who had read the book. The idea was to talk about Black women in White spaces and see how much had changed and how much hadn’t. They said the book really resonated with them and that there were many things about the lives of the young women that echoed in their lives today.

How has life changed for women like Aisha, Crystal, and Serena since 1986? And how has it remained the same?

As much optimism as [we] had, I don't think we could have envisioned a Black president [or] a Black vice president. We were the first generation of young women to go into this world that had been off-limits to our parents in terms of the workplace [and] personal relationships, and that was a revolution.

Black Lives Matter was founded by three Black women, and they are in the same tradition as Serena. For all her psychological issues, Crystal saw herself as an activist. Black women have flowered magnificently in the last 30 years, becoming not just writers winning major awards, but major creatives globally and impacting a whole generation of writers across the board, Black and White.

The changes have been revolutionary, but it’s interesting that we’re living at a time of tremendous political retrenchment. Books like this book might [be] banned if people had their way. The question is, what are women who are coming of age now going to do? How are they going to hold onto the positive changes their mothers brought into the world?

The lives of young people today are constricted in ways that our lives were not. When I was in college, you could graduate and then [get] your own apartment, your own car. Now you graduate with the equivalent of a mortgage. It’s like with everything, the glass is half empty, the glass is half full. But tremendous positive change has been enacted, and Black women are fiercely working to protect that.

A character in this novel claims that everything she writes is autobiographical, and that that holds true for every writer.

I think that’s inevitable. Years ago I met the illustrator John Steptoe, [who] said that there was some reflection of him visually in every face on any of his canvases. There’s something of me in my characters, even when they make choices that are different from mine. I’m very curious, I’m neurotic, I have certain political values that my characters reflect. Our lives are great founts of imagination. I interviewed Toni Morrison once, and she said that ‘ghost stories’ given to her by her family about previous generations informed her work.

Did A Woman's Place serve as a model for writers like Terry McMillan, whose works feature multiple female protagonists, or were other novelists also doing this?

I was inspired by Mary McCarthy. She went to a fancy girls’ school [Vassar] and wrote a novel (The Group) about the friendships that came out of that experience, coming of age in a particular educational setting. I also wanted to write about the ways in which friendship is another way of finding family. I lost my parents when I was fairly young, 22 and 23, and my friendships with women became a place where I found home, where I found myself.

How did McSweeney's come to select A Woman's Place for reissue as part of their Of the Diaspora series?

I’ve known the head of the imprint [Erica Vital-Lazare] for many years. She was a writer nurtured by the Hurston/Wright Foundation, which I founded, and she wanted to rerelease books she felt were classics.

Will there be an audio version?

My agent is trying to make that happen.

Who would be your first choice for the narrator?

Angela Bassett. [laughs]

Were you invited to make any changes to the book?

No, and I wouldn’t do that. This whole thing we’re in now where books that were written in previous eras are rewritten—I despise that. I think that’s horrible.

What’s next for you?

My next book, The New Black Woman Loves Herself, Has Boundaries, and Heals Every Day, came out in May. It’s a series of short essays about my self-care practices. I’ll be doing some more writing workshops, which are all on my website, and I’ve got a novel rolling around in my head that hasn’t claimed me yet.

EPILOGUE

What’s the last great book you read?

Rest Is Resistance, by Tricia Hersey, is about how we need to get off the grind to save our lives and save our souls. That book had a powerful, powerful impact on me. The last novel I read that blew my mind was The Trees, by Percival Everett. Emmett Till comes back to take vengeance on the people who killed him, which sets off a frenzy of other things happening. And it manages to be terribly funny.

Favorite bookstore or library?

I'm not going to play favorites. Go to any that you can. Support them all. I love roaming in bookstores. Many of the books I've ended up loving—books that I’m supposed to read—they find me.

Best place to read?

Once I'm in the zone, in that story, I can read anywhere.

Best time to read?

I have more energy earlier in the day. And reading takes energy.

If you’re struggling to finish a book, do you push through or put it down?

If I'm not enjoying a book, I don’t feel like I have to finish it because I paid for it. I’ve taken books back to Barnes & Noble with the receipt and said, “I don’t want this book.”

Any guilty pleasures?

I’m kind of a snob. [laughs] I read serious books. That’s my fun. I want my brain to be on fire.

Is there a book you’ve reread often?

I used to read War and Peace every couple of years. And Their Eyes Were Watching God.

You’re hosting a dinner party for three writers—dead or alive. Who’s on the guest list?

Zora Neale Hurston would be there. Tricia Hersey would be there. And Joy Harjo would be there. I just discovered her. She’s amazing.

Is there anything else that you’d like to talk about?

For those who are reading this who have the desire to write, I urge you to write. People will say, “You can’t write!” or “Who would want to read that story?” But it’s important to hold onto your unique voice and believe in your unique story. Be humble about learning to write. It’s hard, but if you’re a real writer, that’s what you like about it. You want to learn how to tell a story. I have to learn how to tell a story every time I write a book.

Introduction to A Woman’s Place by Marita Golden

It was 1974, and I was young, gifted, and Black. Living in New York City, I was a charter member of the generation of Blacks who were the first to benefit from the seismic cultural, political, and societal changes wrought by the civil rights and Black power movements. I attended American University for my BA and Columbia University for my master’s degree. At 24 all that was behind me, as was the death of both of my parents within a year and a half of one another.

I was young, gifted, and Black. Working in publishing, freelance writing, taking fiction courses, seeking out Audre Lorde and June Jordan as mentors, falling in love with a Nigerian graduate student who would give me a marriage that would not last, a son who became my North Star, and a story about identity, family and finding one’s voice and home in the world that would become my first book, the memoir Migrations of the Heart.

I was young, gifted, and Black. My appetite for life was insatiable and I had begun to feel the first indications (emotionally and spiritually) that writing would not be a career or a choice. For me, writing would be a calling, and the tool I would use to access a deeper knowledge of the world. Twelve years later, my first novel, A Woman’s Place, was published, a text that like all fiction is in some ways autobiography, a map of a writer’s soul.

As I read this story for the first time in many years, I became deeply emotional. I was swept up not only in the story but by the memories of how and why I wrote it. I remembered that I was amazed to be writing a novel. I had been writing something, anything, everything, since childhood, poems, stories, lists, letters to the editor, articles for the high school newspaper, a column for the college paper. And now my confidence had been bolstered and confirmed by a contract to publish my first novel.

In Migrations of the Heart, I made literature of my life. In A Woman’s Place, I melded imagination with the echoes of lived experience to create a fictional universe I wanted readers to embrace as real. As the author, I was a young Black woman unlike any the world had seen and I knew it. A young, educated Black woman sexually liberated by The Pill, emboldened by the tumult of social change and racial progress purchased in blood, proud to call myself Black, claiming citizenship in the world.

Our foremothers, women like Zora Neale Hurston, Eslanda Goode Robeson, Pauli Murray, and so many other women creatives, intellectuals, and activists/builders, had paved the way. But I was part of, enlisted in a generation of, New Black Women asking revolutionary questions out loud. Who would we love? How would we define ourselves? Could we be race women and still sing our own unique song? Could we say yes to ourselves and mean it?

Yet because novelists are always telling their own story over and over, musing over the legacies of how they have lived, what they have warred with and sought, alchemizing and conjuring all that, A Woman’s Place is my story of allowing language to become my home, my story of discovering that Africa is home and it isn’t and that the continent will break your heart and give you purpose, my story of evolving through marriage and motherhood.

Our mothers raised us to marry and settle down. Many of us did marry. Many of us didn’t. Others of us took lovers, stoked passions of all kinds. We did everything, raised children, and remade every historically White institution we entered. We never settled down.

A Woman’s Place is a novel about the enduring friendship of three women because, after the deaths of my parents, it was the sisterhood of women of all ages that enfolded me and offered me a new family. In the novel, Serena dedicates her life to changing the world and puts her life on the line to do it because my heroes had been the young Black women of the civil rights movement, half a dozen years older than me, who had risked everything to change everything.

Crystal yearns to use language and imagination to live a life that she hopes one day will become “crystal clear.” She knows that poetry can save her life. Faith/Aisha marries as a form of retreat from life and choices. Year later she breaks through the walls of her incubation. Through ruptures, distance, silence these women never let one another go.

A Woman’s Place ranges across continents, racial lines, possibilities, and definitions of self, and in it, I established an elastic blueprint for the novels that I would write later. Novels that I never deicded to write but that possessed me and took me to the river. I like to think that the young women who have declared that Black Lives Matter call Serena their sister. Today’s fiercely talented Black women writers, some of whom I have mentored, understand Crystal’s impulse to scrutinize experience and submit to it, and then stake a claim to her precious Black woman’s story. Black mothers holding their children ever so tight instinctively know Aisha’s dedication to her children and the desire to bequeath to them a truly brave new world.

I was young, gifted, and Black. I came of age reading Nikki Giovanni and Maya Angelou and Gwendolyn Brooks in college and then Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, Toni Cade Bambara, Gloria Naylor. They were my teachers, stars creating a constellation that literally shook the heavens. They remained my teachers even as I joined them in creating Black women’s stories that I wanted to be timeless and knew were universal. Toni Morrison defined our mission when she rejected the power of the White Gaze and asserted the primacy of Black characters inhabiting a Black world.

I was young, gifted, and Black. I made a world in which writing took me all over the world, filled me to bursting with stories that others would claim as their own, inspired me to create community through story wherever I found myself, whatever I did. I was young, gifted and Black. I dreamed a world that came true.

An Of the Diaspora reprint published by McSweeney’s. October 18, 2022. All rights reserved.