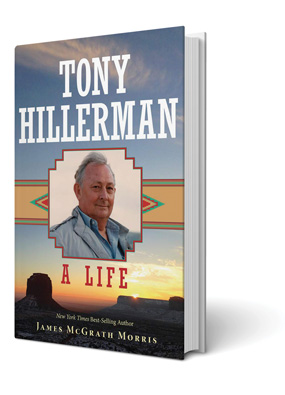

Selecting a subject for a biography is like finding someone to date, says James McGrath Morris, CAS/BA ’96: “The person has to fascinate me, an endless fascination that makes me want to get up in the morning and figure something out.” His latest book, Tony Hillerman: A Life, centers on the New Mexico author who published 18 mystery novels featuring Navajo Nation police detectives at a time when diverse characters were still few and far between.

Why Tony Hillerman?

I felt he was underappreciated as a serious literary figure, in part because he wrote entertainment. People don’t tend to think of mysteries as literature. A biography could help remedy that by making a case that he was up to something more significant. He had such a magnificently interesting life filled with goodness, and that’s rare. There was nothing I found about Hillerman’s life that wasn’t admirable or inspiring.

Were you a fan before you began this book?

Yes, I was. I started reading his books in the summer of ’79. He cleverly uses landscape as a character. It isn’t a backdrop. He uses it to engage his protagonists, Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee. They interact with the landscape—the dryness, the winds, the dramatic sunsets, the tall mountains, the thunderheads—all of those things are key elements to the books.

Where did your research take you?

I was honored to be invited to a Blessing Way ceremony. Navajo ceremonies date back hundreds and hundreds of years, and the continuity is an important part of their culture. You’re connecting with generations and generations who have come before. I also felt an ethereal connection with Hillerman himself because he’d been to a similar ceremony. We were separated by time, two Anglos who’d come to witness and participate in these ceremonies. I left there euphoric—and feeling very privileged.

Did you uncover anything that surprised you about Hillerman?

He suffered from PTSD. This was not a term used during World War II, but he certainly suffered from trauma after—as a teenager—killing other people, seeing his friends killed, and almost suffering a fatal wound. I think there’s a connection between his deeply emotional draw to hózhó, the Navajo concept of seeking harmony, and his writing about the Navajo world and culture and spirituality. It’s tied to his own internal need to find some sort of peacefulness and harmony. I had no idea this was going to be part of the book, and instead it ended up shaping the whole narrative.

How did George Guidall—a prolific narrator of audiobooks, including Hillerman’s novels—come to record your biography of Hillerman?

I interviewed him for the book, because he’s an important part of the story. He said, “When the book’s done, let me know. I’d like to record it.” This is the only book he’s narrated in which he appears. He had to read his own name!

Once you publish a biography, do you think of your subjects as old friends, or are they more like guests who have overstayed their welcome?

It’s very much like a child coming out into the world. When I finish writing a book, I experience something similar to postpartum depression. My wife will testify to it. I get aimless, depressed. But when it’s published, I do get better. People ask me which is my favorite book, and the answer is always the same: You love them all differently. And you love them for their warts too. Tony Hillerman had mistakes in his books, and he often spoke about them. He’s helped me come to terms with speaking about my mistakes, whether it’s a typo or getting something wrong.

As a biographer, how do you ensure authenticity when telling the stories of people whose gender, race, or socioeconomic backgrounds differ from your own?

I confronted that question when I wrote about Ethel Payne, a Black woman raised on the South Side of Chicago. I grew up in privilege as an embassy brat on the East Coast. We couldn’t be more different, although I’m convinced that, had she been alive while I was writing the book, we would have found a lot to talk about: bad editors, writing on deadline, good stories, cooking (I cooked some of her recipes). I had to learn a lot about a culture I wasn’t a part of and try to represent it in a fair way. Biography is like portrait painting. I bring to the canvas my own acculturation, my own values, my own perceptions, but that doesn’t mean I can’t find a measure of fairness in representing another person’s world. Biographers have to be able to do that. Fairness is the ultimate criterion.

How did you become cofounder of Biographers International Organization?

In 2005, I started a free monthly newsletter called The Biographer’s Craft with news about people who had sold books, articles about archives—the kind of thing you’d love to get if you were a biographer. I had about 1,800 readers. One day I thought, “Romance writers have an organization. Mystery writers have an organization. Thriller writers have an organization. Biographers need an organization.” So I wrote an open letter on the front of the July 2008 issue of the newsletter saying that we could have a meeting in New York and see about creating the organization. Eight months later, 50 biographers—from very well-known Pulitzer Prize winners to would-be biographers—showed up for this meeting. We had our first conference the following year in Boston, and the organization now has 600 members, annual conferences, and well-funded fellowships. Frankly, it’s the most successful thing I’ve ever been involved in. The acronym (BIO) was contributed by a reader of the newsletter.

What are you working on now?

I’m involved in producing an edited book called The Writing Life of Writing Lives. These are stories by biographers, tales from the trenches: how they discovered a document, how so-and-so tried to block them from writing the book, things like that. That’s going to take up a lot of my time this year.

EPILOGUE

Are you a fan of biography as a reader?

It’s hard to read a biography for pleasure because I’m so attuned to what the author is doing. It’s like being a chef and tasting someone else’s food.

What was the last great book you read?

The Book of Two Ways by Jodi Picoult.

Favorite bookstores?

Booked Up, Larry McMurtry’s bookstore that was in Georgetown, or the Strand in New York.

Best time to read?

Now it’s in the daytime. I tend to fall asleep when reading a book at night.

Best place to read?

A comfortable chair is perfect for me, as is reading on the couch. If I read a novel at my desk, I’ll feel like it’s work and I won’t enjoy it the way I should.

You’re struggling to get through a book. Do you push through or put it down?

I’ll give it a chance, but I stop reading books in the middle and don’t feel any guilt.

Any guilty pleasures?

Kyra Davis’s mystery series. Those books were like eating chocolate chip cookies and worrying about the bathing suit season that’s approaching.

Book you’ve read most often?

My Antonia by Willa Cather. I’ve reread it several times, and every time it’s gotten better.

You’re hosting a dinner party for three writers—dead or alive. Who’s on the guest list?

John Dos Passos, Rudolfo Anaya, and Donald Hall.