Brian Krasney’s six-month-old daughter cautiously bit into a pancake—fluffy on the inside, crisp along the edges—at Garretts Mill Diner and flashed a toothy grin.

“This is a sign,” Krasney said. Soon after, he purchased the distressed restaurant in Stow, Ohio, fulfilling a delicious dream.

In 2015, Krasney, SOC/BA ’02, was thriving as an IT system administrator—but he was nagged by feelings of nostalgia, fondly recalling days spent hustling on his feet, waiting tables at the Cheesecake Factory in Friendship Heights, instead of slumping in a desk chair. A restaurant itch would have been financially impossible to scratch in Chicago or Washington, “but we’re in Ohio, so what the heck,” Krasney said at the time. “Let’s give it a go.” He checked out 100 restaurants in greater Cleveland and Akron and visited 12 before connecting with a motivated buyer at Garretts Mill.

Today, the business thrives on sweet and savory crepes, fresh fruit, and friendliness. A fire capacity of just 40 and casual, dark green tablecloths create a cozy atmosphere, and the quick conversion of first-time customers into regulars is central to the business model. “We’re not going to compete with your First Watches or Bob Evanses on volume,” Krasney says, “but by the time somebody’s been here a second or third time, we make sure we know their name.”

On a busy Saturday or Sunday, hundreds of hungry Ohioans spend their hard-earned cash and tap their credit lines at Garretts Mill. A single table might turn over six times before close. A staff of nine or fewer works to keep the thousand-square-foot restaurant humming, so Krasney wears many hats: washing dishes, wrapping silverware, and cleaning everything from grease traps to toilets, all while reconciling the incoming and outgoing money for the most fast-paced of businesses.

Increasingly, hash browns and sausage—along with nearly everything else in America—are purchased in debit and credit card taps and swipes and the unfolding of digital wallets. Over a busy week in August, for example, Garretts Mill made $10,600 from dine-in and carry-out service, about 70 percent of which stemmed from card transactions. That’s flipped, Krasney says, from 2015, when physical cash accounted for about two-thirds of revenue.

He’s not blowing applewood smoke. As this Midwest diner goes, so does the rest of the nation. In an August Gallup poll, 76 percent of Americans said they use cash for less than half, only a few, or none of their purchases, compared to 47 percent five years ago.

Krasney leans in slightly toward that trend. A Square-enabled iPad is both a blessing during a weekend breakfast rush and an asset to his neurodiverse team. David, Krasney’s longest-serving employee and a young man with a developmental disability, is more comfortable, from a dexterity standpoint, settling checks via tablet than in cash. Plus, one-tap checkout screens lead to higher tips.

Yet there are far too many competing factors for Krasney to consider making Garretts Mill completely cashless. It’s within walking distance of a Cleveland Clinic facility and is popular among folks who’ve just had their blood drawn. (They trend older and tend to be more cash dependent.) Some of their vendors prefer—and discount—cash payment. Just as a precaution, Garretts Mill doesn’t process card transactions in offline mode when the WiFi’s down. And a handful of Krasney’s employees expect to end a busy shift with some cash tips in hand.

Even as customers largely ditch bills and coins, a small Ohio diner illustrates the à la carte complexities lingering beneath the surface of an increasingly cashless society. The shift away from cash is neither linear nor tidy, and with each decision forces us to confront difficult truths. For whom are we making change, and who are we swiping away?

If you find yourself less frequently in the company of George, Abe, Andy, and Alex, you’re in good company.

The Federal Reserve’s most recent Diary of Consumer Payment Choice, published in May, found that Americans completed just 20 percent of their transactions in cash in 2021. That’s up slightly from a 2020 nadir of 19 percent, but down from 31 percent when the survey began in 2016. Most Americans still prefer to have cash on hand, but a US Bank survey found that 50 percent of adults carry it less than half the time they’re in public.

Square estimates that the pandemic—which necessitated contactless payment—sped up our transition away from cash by about three years. It was well before COVID-19, however, that Street Sense Media, a nonprofit that publishes a poverty- and homelessness-focused newspaper, made a business change to counter the line, “Sorry, I don’t have any cash on me.”

Street Sense regularly makes decisions with its 100-plus vendors, many of whom are experiencing homelessness, in mind. In 2021, it began publishing weekly, projecting that a higher frequency would raise vendor income by 40 percent. It lags its online publication schedule to give vendors the exclusive story in print. And in 2017, it launched a mobile application, allowing customers to pay their vendor using cards or ApplePay.

Safety also factored into the decision. Some vendors prefer operating through the app, says Street Sense editor in chief Will Schick, CAS/MFA ’21, because they believe cash—and the knowledge that they carry it—makes them a target for theft.

Cash is still the preferred means of purchasing Street Sense. (It’s estimated to account for at least 70 percent of vendor sales, with the Street Sense Media app, Venmo, and CashApp comprising the remainder.) But more options—and more frequent publication—allow vendors to reach more customers, even if sales haven’t yet returned to pre-pandemic levels. Through the app, vendors accumulate earnings in internal accounts, from which they can then make cash withdrawals.

“There’s flexibility there. We work with people wherever they are,” Schick says. “We’re about helping people who are low-income” but operate within a society that rarely prioritizes them.

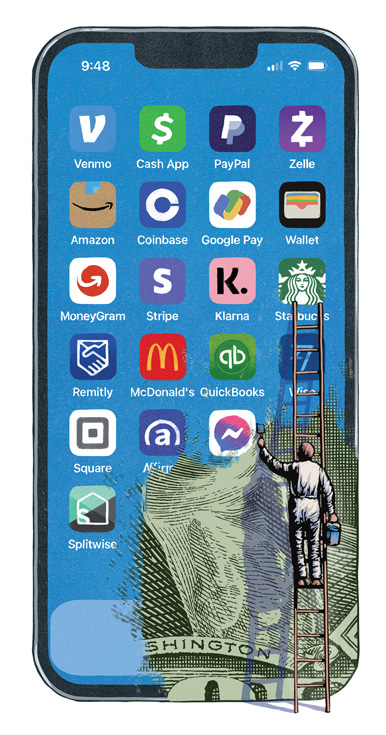

Consumers now pay each other or businesses via hundreds of mobile applications. They can acquire a pastry with their phone and a cup of coffee with their smartwatch, all while earning Delta miles. It has never been easier to make purchases—at least for those who have access to checking and credit.

As of 2019, 6 percent of American adults were unbanked, or without a checking or savings account in the last two years—the most often cited reason for which is an inability to meet minimum balance requirements. Another 16 percent were underbanked, maintaining access to an account but also using alternative financial services like check cashing or payday loans. Those numbers are higher among District residents. Eight percent of Washingtonians are unbanked and another 21 percent are underbanked, according to Bank on DC, a banking access program spearheaded by the DC Department of Insurance, Securities, and Banking.

People with lower incomes are likelier to be cash-dependent, as are people of color. Black and Latinx families account for 32 percent of the population but 64 percent of unbanked and 47 percent of underbanked households, per the Boston Consulting Group. And many communities are becoming increasingly hostile toward their most accessible form of payment.

In February 2021, 15 percent of Square clients in the US that remained open during the pandemic were cashless—double the proportion prior to COVID-19. (In DC, it climbed to 40 percent, up from 15.) This trend comes even as cities like New York, Philadelphia, and San Francisco and states—like New Jersey, Colorado, and, since 1978, Massachusetts—have passed legislation requiring retailers to accept cash.

DC council members unanimously passed the Cashless Retailers Prohibition Act in December 2020. Enacted in early 2021, its enforcement—suspended during the public health emergency—will cost an estimated $171,000 annually. So far, those funds have not been allocated. Reporting on the law’s status in summer 2021, Schick snapped photos in coffee shops, ice cream parlors, and hardware stores that expressed in two words—“no cash”—that they hadn’t yet fallen in line.

Joseph Leitmann-Santa Cruz, SPA/MPP ’23, CEO and executive director of Capital Area Asset Builders, a nonprofit that provides matched savings, cash transfer, credit building, and education programs to promote financial stability and close the racial wealth gap in the DC area, testified in favor of the law before the council in February 2020. Now, as then, he recognizes the efficiency and public safety benefits of cashless systems but urges businesses to consider the message they send.

“This is a system that primarily benefits those who have access to banking and credit services,” he says. “It is not the ultimate objective of the businesses to keep clients away, but in essence, they’re saying, ‘If you're low-income, Black, or brown, this is not a place for you to do business.’”

Leitmann-Santa Cruz believes those who are unbanked are often seen just for their lack of a debit card, rather than humanized and understood for the circumstances that might have precipitated their reliance on cash. Among those we should factor into our cash versus cashless decisions, he says: undocumented individuals, justice-involved citizens returning to their communities, survivors of domestic violence, older foster youth, and those facing housing insecurity.

Schick often thinks of Street Sense’s vendors, sometimes in the latter bucket, and the barriers they face after withdrawing what they’ve earned selling the $2 paper.

“They get the cash, they go somewhere, and then they can’t spend it. Well, maybe this person’s in a [place] in their life where having a credit card is not an option, or they can’t have a bank account [due to] minimum balance [requirements],” he says. “I think for a lot of folks, it’s hard to fathom poverty and understand what it’s like to only have $20 to your name.”

Cash, perhaps counterintuitively, is expensive.

Businesses pay for labor to acquire it, manage it, count it in and out, reconcile it, and, depending on their location, transport it to the bank via a security service. Its mere presence creates exposure to internal and external theft.

Danielle Vogel, WCL/JD ’07, knows green as both payment and produce. On Earth Day 2013, the former Capitol Hill staffer, frustrated by congressional inaction on climate change, opened Glen’s Garden Market, a Dupont Circle grocery store and deli that considered sustainability with every decision it made. In doing so, she became a fourth-generation grocer—but a first-generation grocer in a society that preferred not to use cash.

From the beginning, cash transactions claimed a “small but not insignificant” share, never exceeding 15 percent, says Vogel. (A professorial lecturer teaching entrepreneurship at the Kogod School of Business, she sold the business, now Dawson’s Market, in May 2021.)

Still, Glen’s gladly accepted cash for seven years. It suspended the practice not over preference or security but public health. Early in the pandemic, amid a flurry of local and national business operations orders and guidelines, DC required increased separation between employees and customers, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advised touchless payment where possible. (The latter is the reasoning behind a public health emergency exception to DC’s Cashless Retailers Prohibition Act.)

Vogel gladly complied by going cashless. For one, her business’s banking access shuttered as COVID-19 emerged, ballooning Glen’s cash supply to $10,000—mostly in large bills. “Even if we were to accept cash, there was nowhere for us to deposit it and no way for us to [break] the $20 bills that were coming in,” she says.

More importantly, “from the day I opened my business to the last day I was there sweeping the floors,” she considered the staff her top priority, simplifying an otherwise difficult decision.

“Small business owners do not choose to go cashless to [deliberately] exclude customers from participating in their businesses. None of us would make that choice, especially in the wake of the pandemic. To the contrary, the decision is typically rooted in considerations that include staff safety and loss prevention,” Vogel says. “Increasingly, when the equities are balanced, the scale tips in favor of protecting the team, even when that means missing out on some transactions. That said, it is important to find ways to include and empower the unbanked and underbanked, and that becomes the responsibility of business owners who choose to go cashless.”

Not all businesses confront the same risks. For Seyid Abediyeh, SIS/MA ’84, cofounder and CEO of American Mega Laundromat in Hyattsville, Maryland, “there’s always some fire to put out”—sometimes literally, if a customer leaves clothes in the dryer for far too long. But they only occasionally involve cash.

His coin laundry operation—as the name suggests, the most cash-heavy part of American Mega Laundromat’s business—is self-serve, decreasing contact. And much like the movement of his 100 Iowa-made Dexter washers and dryers, the circular cash flow inside the laundromat—from card-enabled change machine to washers and dryers, then back again—reduces external cash movement. “It’s basically like a revolving door,” Abediyeh says.

He has remained in business since 1997 despite stiff competition because of his ability to serve customers at all income levels, whether they’re pumping quarters to wash clothes or swiping cards for wash and fold service. Even the Bureau of Engraving and Printing once used his washing machines to stress test the new $100 bill.

But Abediyeh has also been successful because he’s unafraid to make tweaks, as he recently did when cash proved costly. In September, he was contemplating a next move for his car vacuum cleaners after they were broken into, and he pulled a pair of vending machines inside after they suffered the same fate.

“Economic times are hard,” he says. “There are people who resort to doing several thousand dollars’ worth of damage to get maybe $50 or $100 in cash out of the machine.”

There will always be fires, but someday, Abediyeh predicts, they won’t involve cash. “A lot more of our customers are now using credit cards,” he says. “Over time, I think most retail businesses will become cashless. Even ours.”

A good laundromat owner can spot a turning Tide.

Amid a new, more technologically advanced financial game, inviting people off the sidelines remains one of our greatest challenges. The path to financial inclusion in an increasingly cashless nation is narrow.

Governments are curious about widening it with technology, as more than 100 have at least preliminarily explored central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). Unlike today’s dominant electronic money, CBDCs would be a liability of a central bank like the Fed rather than commercial banks. The US has investigated a digital dollar’s possible benefits—including more equitable access to the financial system, efficiency, and economic growth—and risks like data security and economic stability, but it won’t proceed anytime soon. In September, Fed chair Jerome Powell estimated it would take “at least a couple years” for the agency to do its due diligence.

In the meantime, the path is lined with potentially dangerous shortcuts. Supporters of cryptocurrencies and so-called stablecoins, whose values are linked to assets like the US dollar or gold, are quick to highlight their ability to reach low-income individuals and tout the racial diversity of users relative to other financial services. It’s true that, by percentage, Black, Asian, and Latinx adults are more likely to say that they’ve invested in, traded, or used a cryptocurrency than White adults, according to the Pew Research Center. But recently, investors have been met by dangerous volatility. The price of Bitcoin, the nation’s most popular cryptocurrency, shot to a record high in November 2021 only to plummet 70 percent over the next eight months.

Businesses from Whole Foods to Home Depot now take Bitcoin, and a Deloitte survey of 2,000 retailers revealed that 75 percent plan to accept cryptocurrency and stablecoin payments in the next two years. Many, however, remain skeptical about their use for daily purchases given their current function: largely speculative assets, or “poker chips,” says Washington College of Law professor Hilary Allen.

“Stablecoins have proven to be expensive, wasteful, and inefficient. That’s a feature, not a bug,” says Allen, who testified about them before the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs in December 2021. “It’s not going to be cheaper than the alternative for everyday people due to the on-ramps and off-ramps” in switching between currencies.

Allen, an expert in financial stability regulation, worked in 2010 on the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, which detailed at length how predatory lending practices contributed to the 2007–08 financial crisis. Today, as she sees aggressive lobbying and advertising efforts to expand the digital asset market, a similar fear lingers. “I get nervous about predatory inclusion,” Allen says, and with it the possibility of financial ruin for vulnerable populations.

Audra Pettus, SOC/MA ’17, director of community relations for SkyPoint Federal Credit Union, meets many clients after this financial low—one that destroyed their standing with and trust in banks. Nearly a decade of working for banks and meeting customers who lacked financial education or a steady paycheck has illustrated a painful truth to Pettus: credit is ruined in an instant and repaired over years.

“Fundamentally, these [systems] have been created to keep people of color in certain situations,” she says. “How do you combat that? You have to work twice as hard to build your financial understanding. That’s where I come in and say, ‘Look, we already know we didn’t make the rules for this game, but how can we learn how to play?’”

Since 2018, SkyPoint, headquartered in Montgomery County, Maryland, has been providing low-income customers a playbook as a Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI), one of 1,100 certified by and receiving grants from the Department of the Treasury to provide unbanked and underbanked individuals access to financial services.

Skypoint, for instance, advertises checking without minimum balance requirements or monthly fees and credit-building products like the Thrive card, which extends a line of credit of up to $1,000—with no credit check—after three months of responsible banking and two months of direct deposit.

The Treasury’s CDFI fund reported more than three million consumer loans in low-income communities in fiscal year 2020, but CDFIs don’t reach everyone who would benefit from their services. Pettus cautions, “We’re one department at one financial institution in one area.” There are some debt profiles she can’t take on, instead referring those individuals to a nonprofit credit counseling service.

But for those she can help—from a college student opening a first checking account to a parent rebuilding their credit after a sour history with another bank—establishing trust is critical. Pettus and her team provide free seminars on everything from life insurance to credit building. They study housing and benefits programs and policies throughout the DC area to better understand the financial landscape for potential clients. And Pettus’s predominantly Black and Latinx team “looks like the communities that we go into.”

Pettus explains to prospective credit union members that credit building is a marathon. Sometimes, a cardholder quickly pays a small bill and pushes onward. Then, an unexpected car or medical expense arises, leaving them temporarily winded. In either case—pay all or pay down—slow and steady progress toward a sustained credit relationship is worth it.

“When you use cash for everything, you have no way of establishing that relationship,” she says. Whether tomorrow brings a big purchase or a loan application, “You will eventually hit a plateau or ceiling. A cash-only lifestyle will only take you so far in this digital life.”

Americans accept change is likely, but they’re not thrilled about it.

A Gallup poll found that while nearly two-thirds of adults believe the US will become a cashless society at some point in their lifetime, only 9 percent would be happy about the transformation.

One possible reason for gloom, says financial planner, wealth advisor, and Kogod adjunct professor Jason Howell, is an acknowledgement of how we all lose in a world of cashless purchases: an unsatisfying tradeoff of greater efficiency, less control.

That includes control over our data, harvested every time we swipe, click, or scan. It also means self-control. As we tighten our grip on cards and smartphones, we loosen our purse strings. Transactions now appear in online accounts in seconds and settle in days, making it both simpler to bank—and to forget about a luxurious line item.

“It’s too easy with online banking to think, ‘If I want to look at it, it’s there,’” Howell says. “So, guess what, you’re never going to look at it.”

The Fed’s 2016 Diary of Consumer Payment Choice reported an average cash transaction of $22, compared to $112 for noncash purchases. This pattern bakes in our tendency to use cash for cheaper purchases and to let our guard down more with a card than its paper counterpart. It’s less painful to swipe than to surrender a stack of numbered bills.

“If you count out the 10s and 20s in your hand, then throw in a couple more bucks for tax, you start to think, ‘Maybe I don’t need a new pair of shoes right now. Maybe I can wait until this is on sale.’ It becomes much more tangible,” Howell says. “We receive convenience, and so we benefit in that regard, but that is also the gateway drug to greater spending.”

If our future is destined to be cash-free, Howell says, then we need to make time for financial fitness, just as we would physical or mental health. That means developing a weekly habit of examining transactions, categorizing them, and asking with each budget group, “Is that my intention?” The practice can help consumers add to digital piggy banks, freeing up money for a rainy day—or a well-deserved treat, like a Sunday brunch at their favorite diner.

At Garretts Mill, $8.75—plus tax and a tip for David and his colleagues—buys a full stack of pancakes, the house specialty for more than 20 years.

Here, you’re still welcome to pay for them with cash or card. Either way, the pancakes will appear atop your green tablecloth all the same: piping hot, fluffy on the inside, crisp along the edges, and certain to induce a smile.