The opening of a major institution in the nation’s capital is a rare occurrence and always big news. But Washington’s most recent ribbon-cutting drew special attention. With its dedication in November, the half-billion-dollar Museum of the Bible became one of DC’s largest private galleries—and the only one centered on religion.

Situated just three blocks off the National Mall, the striking eight-level building, with its dramatic glass roof that resembles the leaves of a book, tackles a challenging subject—especially today as a diversifying and polarized America struggles with its religious identity. Debates rage over what it means to be “religious” and about the role the government should play in advocating for and communicating about faith. For these reasons and more, some see the museum as important and full of civic potential.

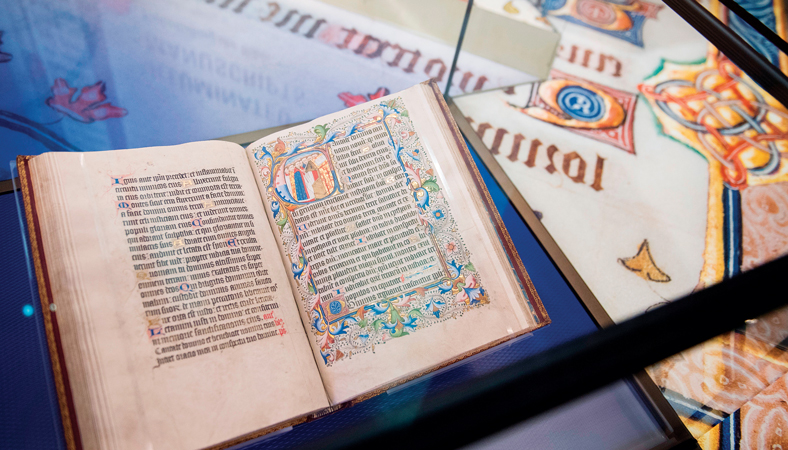

But many, particularly biblical scholars, are deeply skeptical of the institution, in part because of its backstory. The museum was founded by the Green family, conservative evangelical philanthropists from Oklahoma who established the Hobby Lobby craft store chain in 1972. Steve Green, president of Hobby Lobby and chair of the museum board, purchased his first biblical artifact—a fourteenth-century manuscript called the Roseberry Rolle—in 2009. Today, his collection contains more than 44,000 biblical relics and manuscripts, a treasure trove worth an estimated nine figures.

“None of us have this book figured out,” Green said at the November 17 dedication. “We are all on a journey. We will never fully delve the depths of this book—that’s an amazing part of this book. . . . But we want to take a moment to set our differences aside and say, here’s a book that has changed our world, that has impacted lives, and we want to celebrate it in this facility. We want to motivate people to engage with the book.”

The Greens became heroes to many religious conservatives in recent years after they fought the Affordable Care Act requirement that employers provide no-cost birth control coverage under their employee health care plans. In 2014 the Supreme Court ruled that for-profit companies in some cases uphold particular “religious beliefs” and found in favor of Hobby Lobby.

Between the museum’s mission statement—to “bring to life the living word of God . . . to inspire confidence in the absolute authority” of the Bible—and its nearly homogenous white, evangelical Protestant, male board, the new museum is proving to be a Rorschach test for visitors, evoking very different reactions depending on how one sees the role of religion, specifically the Judeo-Christian tradition, in public life.

In the five months since the museum opened in a century-old former refrigerated warehouse, its leaders have continued the juggling act between the motivations of its evangelical board and founders and those of its large and diverse crew of scholarly advisors. Many of these scholars want visitors to understand that there is no one “Bible,” but rather a mysterious and sometimes contradictory series of texts that have been cited as inspiration for everything from marriage and nationalism to slavery and the Civil Rights movement.

These complex and sometimes competing goals—to educate and evangelize—have produced an institution with multiple identities. It will likely take years for a broad array of impressions to seep into the public conversation. In the meantime, we asked three AU experts—professors Evan Berry and Pamela Nadell and university chaplain Mark Schaefer—to let us chronicle their collective first visit to the museum, which sits south of the National Air and Space Museum in Southwest DC. Admission is free, although donations are encouraged.

In the three hours we spent at the 430,000-square-foot museum, we toured several of the permanent exhibitions, which are largely contained on three levels. We started on the “history” floor—the largest exhibition space, at 50,000 square feet—which displays more than 500 texts and artifacts. Many come from Steve Green’s personal collection, including Bibles belonging to Babe Ruth and Elvis Presley and the 1,245-page “lunar Bible,” presented on microfilm, that traveled to the moon on Apollo 14 in 1971.

The museum’s content director, Seth Pollinger, said there was a deliberate decision not to attempt to tell the history of how the Bible was assembled over time and by whom because that would likely be too divisive, plus there is so much that isn’t known.

There are also dozens of versions of the Bible. “Does everyone read the same Bible?” asks a display panel in the exhibit. “People from various religious traditions read the Bible. However, not every tradition reads a Bible containing the same set of books. Even within traditions there are sometimes differences in the number, order, and name of the books. Yet each one is a Bible.”

The history section chronicles how the full Bible has been translated into more than 600 languages (you can read the New Testament in about 1,500 languages) and how it has been passed from one generation to the next and spread around the world. As visitors browse the artifacts, including first editions of the King James Bible and clay tablets from the time of Abraham, they can listen to audio excerpts of people reading the Bible in various languages.

On the lively “narrative” floor, a 45-minute, Disney-style show animates a slice of the Hebrew Bible with flashing lights and immersive art, while a booming, Israeli-accented voice tells visitors about the “chaos of man’s rebellion against his Creator.” As people walk through a maze of displays they learn versions of the stories of Abraham, Moses, Passover, the Exodus, and the delivery of the Ten Commandments. The floor also includes a re-creation of a rustic village in Nazareth at the time of Jesus and a film about the New Testament.

We concluded our visit on the “impact” floor, which opens with a display of luxurious tapestries that depict New World settlers peacefully sharing scripture with Native Americans. This hall features more than 35 exhibits devoted to the influence of biblical text on politics, health, technology, and even fashion and music, in the United States and around the world. Objects on display range from a pair of Gianni Versace suede crucifix pumps to a replica of Johannes Gutenberg’s mid-fifteenth-century printing press, on which he cranked out copies of the Latin Bible—the first major book printed with moveable type in Europe. Visitors can also gather around a virtual dinner table to join, alternately, a Coptic Orthodox family in Egypt, Catholics in Ireland, and Baptists in the American South, as they give thanks before a meal.

“Over time, the Bible helped inspire the country’s ideas about democracy and the belief that religious liberty was essential to its success,” reads a panel near the exhibit hall entrance. “It influenced many national debates, including the abolition of slavery and campaign for civil rights. Frequently, people on opposing sides of an issue appealed to the Bible to support their cause.”

One of the most striking items here is the exact, full-size replica of the Liberty Bell, made in 2003 by the Whitechapel Bell Foundry in London, where the original was produced. The Pennsylvania General Assembly ordered that bell in 1751, choosing for the inscription a biblical verse from Leviticus 25:10—“Proclaim liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof.” Much attention is paid to America’s founding fathers, including Thomas Jefferson, who literally snipped out the supernatural parts of the Bible with which he didn’t agree.

The museum is packed with $43 million worth of cutting-edge technology, including 384 monitors, 93 projectors, 83 interactive elements, and 12 theaters. Visitors are invited to engage with the exhibits at nearly every turn. Using touch screens, they can research the biblical origins of their name or provide a one-word description of how the Bible makes them feel. (Among the responses: blissful, powerful, humble, strong, and alive.) For an extra $8, museumgoers can virtually fly over Washington for a bird’s-eye view of biblical influences around the city.

DC’s most provocative new museum inspires anything but a neutral reaction. AU’s trio of experts turned out to be a critical cohort, as is typical of scholars and academics. They all came away with the general objection that the museum presents the Bible as a cohesive book rather than multiple discrete texts, the content of which must be interpreted individually. What follows is our experts’ critiques, in their own words.

Professor Evan Berry

Today, when we talk about the relationship between the American political project and our identity as a “Christian nation,” it increasingly feels ambiguous. . . . . Americans don’t know the Bible very well, as a document. A lot of what is happening under the banner of “American Christian identity” isn’t biblically grounded (like our right to have guns, for example).

What worried me—is this a private foundation with very particular interests in the kind of religious message they want to develop? The message has evolved, but it is still there. My question is: to what degree is this Christian proselytizing masquerading as a public museum?

As something to be excited about, the museum renders concrete a set of conversations in our nation that are often running below the surface. What I wonder is—if visitors won’t understand the difference between a private foundation and a Smithsonian museum, and they’ll take “the story” as presented here as a sort of gospel truth.

Underlying a lot of the material in the museum is a strong suggestion that there is a “thing” called “the Bible” that transcends not only divisions in Christianity but between Christianity and Judaism—that there is a stable core text. It requires a lot of work to maintain that pretense throughout the three main exhibits that the Bible is one discrete thing—a lot had to go into making it appear that the Bible is a thing.

There is an implicit message in the museum that the Bible is an active agent and we are passive recipients—as opposed to vice versa.

I see the museum’s location as a move to get their foot in the door, in the conversation, to claim space in the political theater that is Washington, DC.

Berry is a professor and director of graduate programs in the Department of Philosophy and Religion.

Professor Pamela Nadell

I think someone who’s not religious or has little to no understanding of the Bible would be surprised by the extent to which it has influenced American society. We tend to think of the First Amendment as creating a major wall separating church and state. But those of us who know US history understand it’s more like a porous boundary that has changed and shifted over time.

Many people don’t know that, until the 1960s, children in public schools had daily Bible readings and recited the Lord’s Prayer. There is a dearth of religious literacy. Most people in this country really don’t have a concept of how the Bible was the foundational text of Western civilization— and also, as a result, of American civilization.

The reality of the museum is its message is about the impact of Christianity on America. It wants to deepen that impact. Its location alone—just a stone’s throw from the Capitol—makes a very powerful statement.

It doesn’t say so explicitly, but my takeaway is that this is a museum that celebrates Christianity’s role in American life and wants to advance that project. It avoids any kind of conflict anywhere. It’s so clear there is an evangelical agenda, but it’s never stated. People bring what they know or don’t know about the Bible as they go through the exhibits. The curators had an enormous opportunity; they spent many millions of dollars on exceptional design and high-tech elements everywhere. But it would be fairer to the audience if they conveyed the museum’s biases at the outset.

You’re expecting the museum to be historically accurate, but its job is not to convey historical complexity: instead it aims to evoke emotion that people will carry away with them. Some of the exhibits we visited reflect a trend of museum-as-theater. (Is ‘Disneyfied’ a word?) But who is coming to the museum? Maybe most people don’t look for complexity and nuanced interpretation.

Nadell is the Patrick Clendenen Chair in Women’s and Gender History in the College of Arts and Sciences and chair of the Jewish Studies Program.

Rev. Mark Schaefer

My concern was that religion not be seen as anti-intellectual. I didn’t want this to be along the lines of the creation museums and theme parks, where Adam and Eve are riding dinosaurs.

The museum is not that, but I didn’t see anything to address the reality that we read the Bible so differently than people 500 years or 1,000 years ago would have. That’s a function of human psychology, sociology, and cultural background.

If you had no knowledge of the Bible whatsoever, you could learn some interesting facts. But you don’t gain a deeper sense of the text and how it came into being. It’s treated more like cultural artifact rather than something with its own organic life and history. It was more about how the Bible was received, printed, and preached about rather than, who wrote this text? What are the challenges associated with it? Those questions are important if you’re going to have an honest relationship with the text.

Let’s say I don’t know much about the Bible, Christianity, or religion. I come to this museum—what have I learned? That there are a bunch of ancient texts—and a basic narrative that brings me up to the knowledge of the average Sunday school attendee. I have learned the Bible was somehow influential in US history, but it’s a confirmation bias. It will draw people who are inclined to agree with the philosophy of the museum itself.

I’d love to see a museum of the written word. You could have the Bible, legal texts, Shakespeare—have a whole alphabet wing. That way you could have a treatment of scriptures that would come from the point of view that doesn’t see the Bible as this object outside of history. In my experience, the more of the history, the more of the text criticism I learned—the more wondrous it became to me. When it was removed from, ‘This sacred story dropped out of the sky’ thing, that’s when it started to become even more meaningful to me.

Schaefer is a United Methodist pastor and AU’s 10th university chaplain.