Humanities

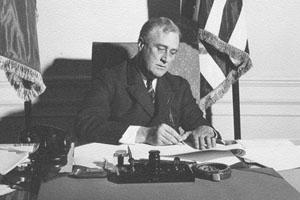

Roosevelt Neither Villain nor Hero for the Jews

Accounts of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s response to the suffering and slaughter of Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe have painted him as scourge or savior. Either he moved heaven and earth to help the Jews, or he turned a blind eye to their situation and did nothing.

But in their new book, FDR and the Jews (The Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2013), American University history professors Richard Breitman and Allan J. Lichtman show that these extreme narratives fail to reveal the true strengths and failings of Roosevelt and of his presidency.

A true evaluation of Roosevelt’s actions calls for a more in-depth understanding of Roosevelt the man, his allies and adversaries, and the time during which they lived.

"The Holocaust is a morally charged subject, and people would like to draw clear lessons from it," Breitman said, a historian of Nazi Germany and the Holocaust. "Most of those who have written before strove for accuracy, rather than polemics, but history is often complicated, and FDR's history is particularly so."

The idea for the book seeded nearly 30 years ago when Breitman was working on his 1987 book coauthored with Alan Kraut, also a history professor at American University.

"I noted that Roosevelt was something of a puzzle," Breitman said. "I wrote what I thought was a solid chapter on him, but I wished that I had had more sources. I just was not convinced that they existed."

While FDR left many documents, his paper trail was generally lacking. Especially, Breitman and Lichtman say, when it came to sensitive subjects, such as the Holocaust.

One of the Most Private Leaders in U.S. History

"We describe him as one of the most private leaders in American history," Breitman said. "FDR wrote no memoirs and precious few revealing letters, notes, or memos."

Breitman and Lichtman say FDR did not regularly tape conversations in the Oval Office—the audio archives of his Oval Office recordings are press conferences and some snippets of conversation that were accidentally recorded. He prohibited minutes at cabinet meetings or other presidential meetings so as to encourage people to speak freely.

"Much of what we know about his statements—even in private official settings—comes from other people who kept diaries or otherwise reconstructed his comments," Breitman said.

But years later, while Breitman was working on a project to publish the diaries and papers of James G. McDonald, chair of Roosevelt’s Advisory Committee on Political Refugees, he and his colleagues discovered a previously unknown document reconstructing an April 1938 conversation in which FDR said he would like to get all the Jews out of Europe.

"This very surprising document, combined with a range of other newly available sources convinced me that one could now do a more nuanced and thorough study of Roosevelt, showing how his attitudes and policies evolved over time," Breitman said.

When Breitman decided to include Roosevelt’s early life and politics in great depth, he turned to his friend and American University colleague, Lichtman, a renowned presidential historian.

"FDR’s childhood was one of a privileged white protestant," Lichtman said. "While most of his peers and their families would have espoused anti-Semetic beliefs, FDR did not. His parents did not have anti-Semitic beliefs. They inculcated tolerance in him and led by example. His mother was involved in Jewish charitable work and received an award for her efforts."

FDR Did More Than Did Any Other World Leader Of His Time

In their research for FDR and the Jews, Breitman and Lichtman scoured numerous libraries and archives for documents that, for the first time, present a full picture of a president weighing conflicting priorities in a country contending with depression and world war.

Drawing on these sources, Breitman and Lichtman debunk such persistent myths as Roosevelt’s culpability in the turning away of the S.S. St. Louis carrying 937 German Jewish refugees and his administration’s decision against bombing Auschwitz. The book also provides fresh insight into FDR’s position on Palestine and his relations with Jewish advocates and world leaders.

And in a discussion with important implications for today, Breitman and Lichtman reveal how limited information, bureaucratic languor, and domestic political contingency can prevent a president from responding to foreign atrocities as forcefully or as quickly as circumstances demand.

"We have seen examples of this with presidents who came well after Roosevelt—who didn’t perform as well as Roosevelt did," Lichtman said. "President Jimmy Carter, the great humanitarian, didn’t act on the devastation in Cambodia. President Bill Clinton didn’t act on the genocide in Rwanda. And now, President Barack Obama is challenged with what role the United States should have in addressing the crisis in Syria. All presidents deal with competing priorities and complex situations that vary with the times. And the answer of how or whether to respond is never simple."

In FDR and the Jews, Roosevelt’s failings emerge clearly. But so, too, does the fact that Roosevelt did far more to help European Jews than did any other world leader of his time.

Breitman and Lichtman will discuss FDR and the Jews from 7 to 9 p.m. on Monday, April 22, in the Abramson Family Recital Hall in AU’s Katzen Arts Center. The event is free and open to the public.

Videos produced by Richie Giese and Maggie Barrett