Achievements

New Oral History Project Reveals Untold Stories About the Civil Rights Movement

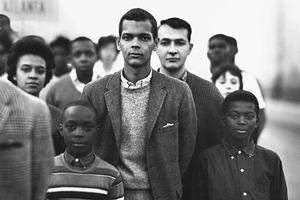

Sitting across the table, Charlie Cobb shifted his weight and settled in to be interviewed. Gregg Ivers, Professor of Government at American University’s School of Public Affairs, sat opposite him, readying questions about Cobb’s role as a field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) during the civil rights struggles of the early- to mid-1960s. Their conversation looked back at a crucial moment—part of history, but in reality not all that long ago.

Cameron Burns, SPA/BA’20, helped film and conduct the interview, now part of an archive comprising the Julian Bond Oral History Project. The project, named after the late civil rights leader and beloved SPA professor Julian Bond, includes 25 video interviews to date. Video subjects include veterans of the civil rights movement, journalists who covered it, and members of Bond’s family.

While the conversation with Cobb was recorded at the African American Civil War Museum in Washington, D.C., the Oral History Project reaches far beyond the D.C. area. Ivers interviewed subjects in Atlanta, Baltimore, Charleston, Cambridge, Mass., New York City, Philadelphia, Memphis, Jackson, Miss., and Chapel Hill, N.C. His efforts produced a tapestry of stories about civil rights history you never knew, perspectives you’ve never heard, and names you may not yet recognize.

“When I began this project, I wanted to focus my attention on the early life and legacy of Julian Bond and allow my interviewees to fill in important details about their own work,” said Ivers. “Five minutes into my first interview, I realized there was much more that people needed to know. People tend to associate the civil rights movement with two or three visible iconic figures and a handful of violent moments that resulted in major social transformation 50 years ago. But that doesn’t even come close to what this movement and period were all about.”

Charlie Cobb was born in Washington, D.C., but grew up in Springfield, Massachusetts. His family had deep roots in higher education and his father was a minister in the United Church of Christ. He refers to himself as part of the “Emmett Till Generation,” a time when the impact of Emmett Till’s brutal murder caused outrage among African-Americans—young men in particular. Till’s murder, and the lack of consequences for his killers, galvanized activists by visibly reinforcing the pervasiveness and brutality of American racism, racial oppression, and racial violence. Cobb, like Till at the time, was just 14 years old.

Charlie Cobb was born in Washington, D.C., but grew up in Springfield, Massachusetts. His family had deep roots in higher education and his father was a minister in the United Church of Christ. He refers to himself as part of the “Emmett Till Generation,” a time when the impact of Emmett Till’s brutal murder caused outrage among African-Americans—young men in particular. Till’s murder, and the lack of consequences for his killers, galvanized activists by visibly reinforcing the pervasiveness and brutality of American racism, racial oppression, and racial violence. Cobb, like Till at the time, was just 14 years old.

“The double-truck photograph of Emmett Till in his coffin literally stopped us guys. That stopped us in our tracks,” said Cobb during the interview. “I can still remember standing on the street corners with five or six of us looking at this picture, knowing somewhere in our guts, even if we didn't know what we were gonna do, this was going to end with our generation.”

Cobb would go on to actively participate in sit-ins and protests; he was once arrested in Baltimore for refusing to leave a pizza shop that wouldn’t serve him. Within a year, he had traveled to Mississippi to help with voter registration work in the Delta region. This area, which contained the town of Money where Till was murdered, was the most dangerous and foreboding place for African Americans in the state.

“Because Emmett Till's murder had completely defined my thinking about Mississippi, the idea that students were protesting in Mississippi was a radical new idea for me,” said Cobb. “I felt it was one thing for me to be sitting-in in Maryland, but something qualitatively different for students in Mississippi, this place where Emmett Till was killed, to be protesting.”

In the addition to his voter registration efforts on behalf of SNCC, Cobb spent the 1960s assisting in civil rights projects throughout the south. In 1965 he helped manage Julian Bond’s successful campaign for the Georgia Legislature. Bond’s campaign was a litmus test for Black politics; could a new generation of Black activists establish the groundwork to elect candidates in urban areas, where African Americans were moving in increasing numbers?

Cobb’s most famous contribution to SNCC was the memo he wrote proposing Freedom Schools as part of the 1964 Mississippi Summer Project, better known as “Freedom Summer.” These schools, he wrote, should be designed to “fill an intellectual and creative vacuum in the lives of young Negro Mississippians.” They needed “to get them to articulate their own desires, demands, and questions and to stand up in classrooms around the state and ask their teachers a real question.”

Cobb believed in young people and their special energy for activism, community building, and meaningful social change.

“Certainly, American University does not lack for students who want to engage the world on matters important to them,” said Ivers. “It always surprises them to learn that so much of what they’re doing, from messaging to political organizing, has its roots in the civil rights movement. A lot of this gets left out in the conventional curriculum.”

The Student Voices portal features oral history interviews with key figures from the civil rights and other social justice movements conducted by AU students. Bringing students into this work is very important to Ivers. More than a dozen current and former students have assisted with interviews, filming, production, and research.

“I think this is very important work and I’m so happy that this is a project of American University,” said Isabella Dominique, SPA/BA’20, president of American University’s NAACP chapter. “During my interview, Professor Ivers asked great questions that helped me think more about my life. It was an interesting way for me to tell my story, how I think about my identity, and it helped me learn more about who I am.”

Like Cobb, the other Julian Bond Oral History Project interviewees tell personal stories about their journey into and through the civil rights movement. These histories, some of which have never been fully documented by academics and journalists, relate the experiences that motivated their decisions, their approaches to social change, and the social, political and legal strategies developed and utilized to achieve those goals.

To watch Ivers’ interview with Cobb, visit the Julian Bond Oral History Project website, which includes videos, photos, and transcripts of these interviews. For further information, please feel free to contact Ivers at ivers@american.edu, or follow him on Twitter at @GIvers1023.