You are here: American University Centers Latin American and Latino Studies Cuba After the July 11 Protests - Eaton

U.S. Government Democracy Projects in Cuba: Following the Money[i]Tracey Eaton

Abstract: Democracy promotion efforts targeting Cuba intensified under the Trump administration, but publicly available spending records do not show any evidence directly linking U.S. projects to the July 11 protests in Cuba. The U.S. Agency for International Development and the State Department have been helping to finance Cuba’s internal opposition for decades. The agencies and their partners often target marginalized populations. Secrecy surrounding their work makes it difficult to know what they do in Cuba and whether they are effective. Funding specifically aimed at increasing human rights in Cuba rose during the Trump administration, hitting a high of $6.7 million in 2020, the single highest yearly total recorded over the past two decades, according to an analysis of more than $218 million in State Department and USAID disbursements. The dollar amount spent for projects that are undisclosed or whose descriptions are redacted also rose, increasing by 74% under Trump, when compared to the Obama administration.

__________

On Jan. 3, 2021, the following email appeared in my inbox, “My name is Kenneth Carter, this is a second attempt to contact you from the US Department of State in reference to your FOIA request submitted on October 8, 2011 assigned case number F-2011-25233. Please verify if you are no longer interested in processing this request or still in need of the requested information.”

I replied immediately. “Yes, I am still interested in the information. I did not see your first attempt to contact me. Please confirm that you received this email so that I know we are in communication.”

I began tracking U.S. tax dollars spent in Cuba more than a decade ago and have filed more than 100 Freedom of Information Act, or FOIA, requests to learn more about U.S. government activities in Cuba. A network of U.S. government-financed groups run democracy programs in Cuba.[ii] Public records reveal only fragments of the mosaic. The government doesn’t regard any of the programs as classified or covert, yet officials keep many details secret from not only the public, but members of Congress.

The unprecedented July 11 protests in Cuba heightened interest in U.S. democracy promotion programs in the country. Precisely what role the U.S. government played in the street protests is beyond the scope of this paper, but I will examine U.S. government spending documents to try to determine if any projects or programs may have foreshadowed the protests. I will also provide some insight into what organizations receive funds and how transparent the U.S. government is about their activities. Such questions are important because they can shed light on U.S. efforts to bring about a democratic transition in Cuba more than 60 years after Fidel Castro took power.

Figure 1 – The USG dataset contains $218,367,438 in Cuba-related disbursements.

The USG dataset includes more than 100 grant recipients and has information on $218,367,438 in disbursements by the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development. (Eaton 2021, Data 1)

Background

U.S. democracy programs are authorized and financed under Section 109(a) of the Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act of 1996, also called the Helms-Burton Act, and Section 1705 of the Cuban Democracy Act of 1992.

The language used to describe project goals has evolved, ranging from “hastening the transition to democracy” to supporting “a peaceful democratic transition” and strengthening “the capacity of independent civil society groups in Cuba to advance civil and political rights.” The purpose has remained the same: To promote democratic change and end socialist government rule on the island.

U.S. agencies often intensify their efforts and boost funding when they believe that Cuba’s socialist government has become more vulnerable. Political pressure from lawmakers and the White House can also influence the programs.

Donald Trump reversed Barack Obama’s policies of engagement and tightened economic sanctions against Cuba. (Federal Register 2017). Officials worked to strangle the Cuban economy, targeting tourism, medical diplomacy and other revenue sources, then they funded democracy projects in the same areas.

In August 2020, USAID offered $3 million for a “development program” aimed at “exposing exploitation” of Cuban laborers. “While the regime earns heavy profit from foreign tourists’ purchases for five-star hotels, beach resorts, so-called ‘nostalgia tours’ and cosmetic-surgery packages, the Cuban laborers who support these lucrative businesses – most of which are owned by Cuban military elite – live on a few dollars a day. For 2020, USAID will expand its support to nongovernmental organizations, legal networks and journalist organizations that further examine the unfair exploitation of Cuban laborers, including sex workers, and the realities under which they live.” (USAID 2020).

In May 2020, the State Department offered $2 million to investigate, among other things, Cuba’s medical diplomacy program. U.S. officials said the Cuban government was exploiting doctors financially and using the proceeds to deny its citizens of basic rights. “This repression is financed in large part by the labor exploitation of medical workers and other service providers, who receive only a fraction of the salaries paid by third countries for their services and often face threats from their Cuban government handlers to discourage them from absconding.” (State Department 2020, May). “Shame on you,” Cuban diplomat Josefina Vidal tweeted in response. “Instead of attacking Cuba and its committed doctors, you should be caring about the thousands of sick Americans who are suffering due to the scandalous neglect of your government and the inability of your failed health system to care for them.” Since 1963, Cuba “has sent more than 400,000 medical professionals on 164 missions to countries in Africa, America, the Middle East and Asia.” (UNESCO 2020).

In June 2019, USAID announced plans to spend $2 million to promote human rights in Cuba and spread awareness of the “failures” of the Cuban revolution. “Programming under this area aims to build and support a democratic culture in Cuba through greater access to independent, legitimate and uncensored information about the realities faced by Cuba’s citizens. The program seeks to garner greater respect for human rights in Cuba by helping to dispel the myths about the successes of the Cuban Revolution and exposing information about the realities of Cuba’s institutions — including its education and healthcare systems, and treatment of Cuban workers and corrupt economy.” (USAID 2019).

The U.S. government has been helping to finance Cuba’s internal opposition for decades. Cuban exile groups have complained that not enough money reaches people on the ground. In March 2008, the Cuban American National Foundation, an influential exile organization, issued a scathing report about USAID’s Cuba programs. “…We have concluded that the US Government program in support of a democratic transition in Cuba has been rendered utterly ineffective due to restrictive institutional policies and a lack of oversight and accountability of grantee recipients…A significant majority of the funds destined for Cuba’s beleaguered opposition are actually spent in operating expenses by U.S. based non-profits.” (CANF 2008).

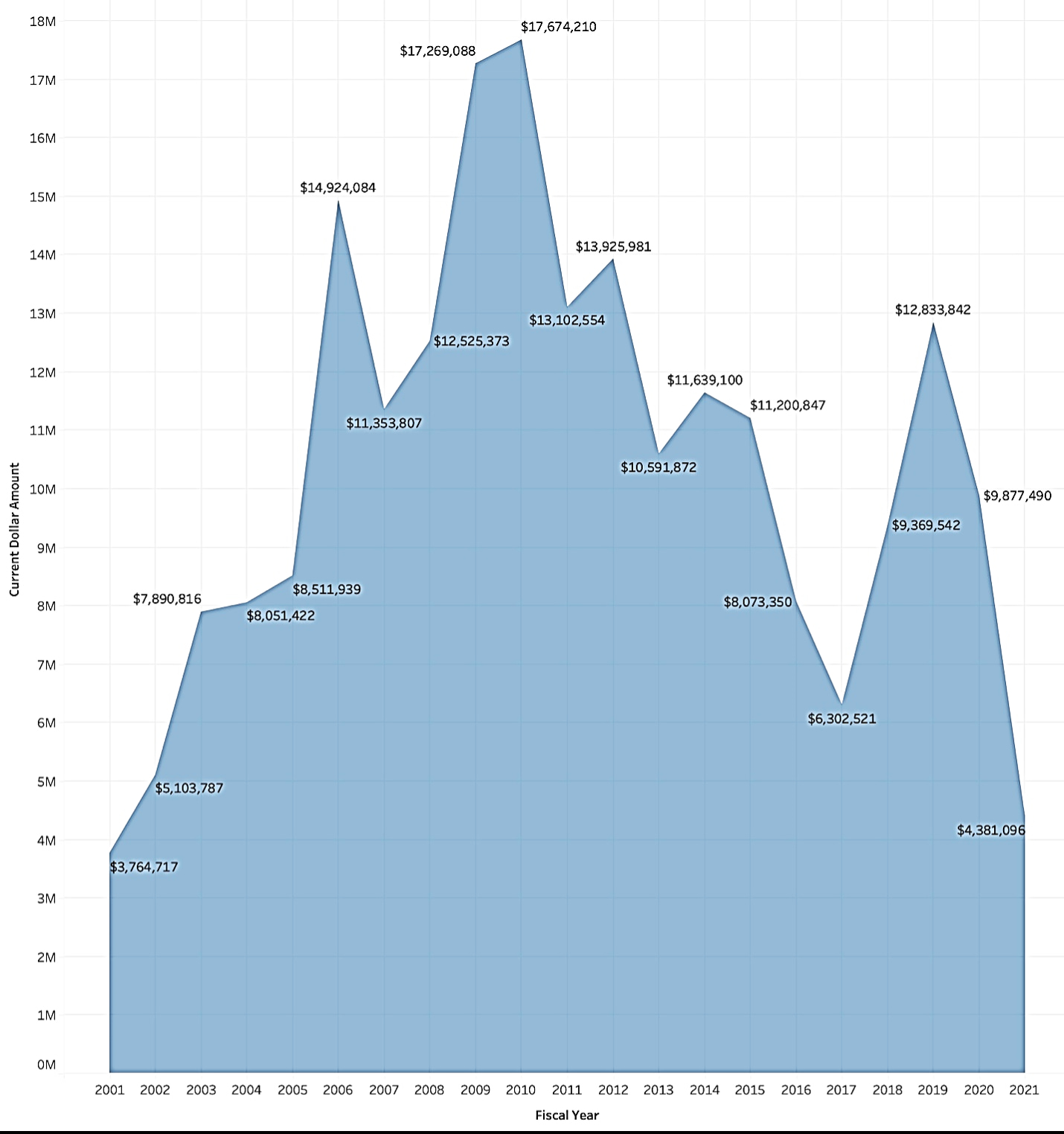

CANF also said the U.S. government should stop awarding grants to universities for studies on transition scenarios and related topics in Cuba. Universities and research institutions in the USG dataset received $14,370,821 in funds from 2001 to 2013. (Eaton 2021, Data 2). Some programs funded academic research. Others financed secretive civil society programs. Loyola University operated a program called CNECT, aimed at serving “a wide variety of Cubans with special attention to the poor, to Afro-Cubans, to women, and other marginalized populations.” A 33-page document about the program obtained under the FOIA (USAID, n.d.) is almost entirely redacted, other than indicating that the project sends trainers to Cuba for some undisclosed purpose. (Figure 2).

Figure 2 – USAID redacted the number of trainers sent to Cuba per year as part of the CNECT program.

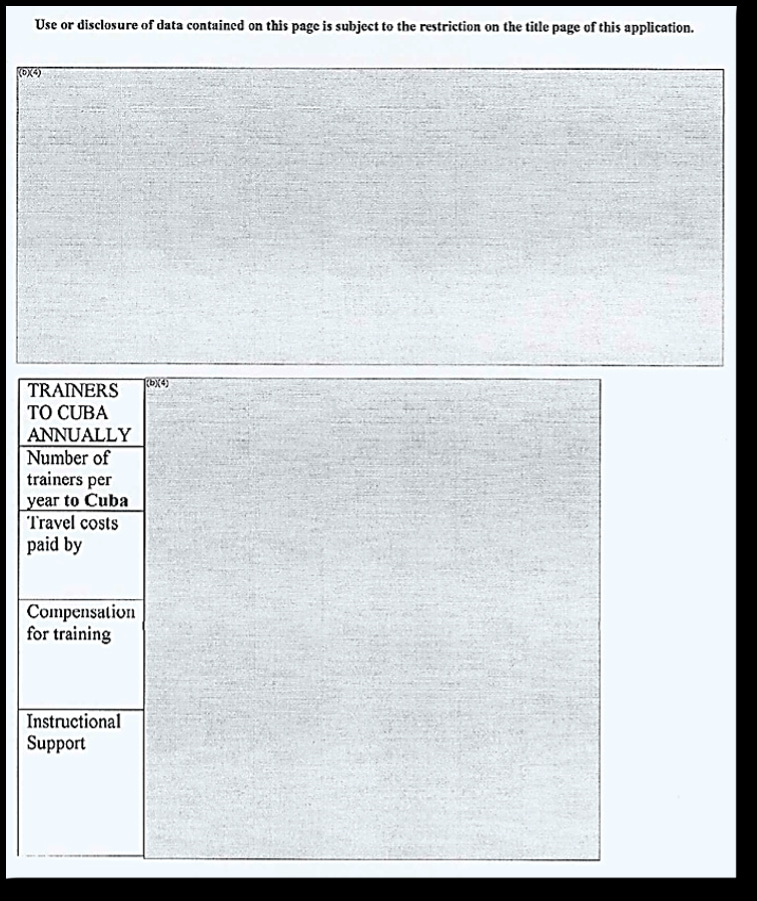

U.S. government agencies and their partners often target marginalized populations. After development worker Alan Gross successfully set up satellite Internet sites for Jewish synagogues in Cuba, his contractor, Development Alternatives Inc., asked him to propose “follow-on” activities “targeting new groups such as African-Cubans, women, youths and other religious groups.” (Gross 2013). Gross said he was not entirely comfortable with the request, but complied. (Figure 3).

Figure 3 - This graphic illustrates the idea of expanding the project to reach "youth, women and Afro-Cubans"

Cuban authorities arrested and jailed Gross in 2009. After his arrest, he said DAI contacted his wife in Washington, D.C., and said they needed to stop by the couple’s home to pick up his personal laptop and “wipe” certain information from it for his “protection.” “My attorneys and I have not yet been able to determine with any certainty what information DAI deleted from my laptop or what other modifications DAI may have performed.” Details of his activities in Cuba probably would have not been disclosed if not for his arrest and subsequent lawsuit against his employer. Cuban authorities freed Gross on Dec. 17, 2014.

The case of Alan Gross highlights the perils of working in Cuba. After his arrest, some NGOs reduced travel to the island. But USAID’s partners quickly decided that face-to-face contact in Cuba was essential. Creative Associates International, the company that oversaw the ZunZuneo project, stated in an internal report: “Cuba travel may be cut back to respond to risk or cost considerations, but excessive reduction may easily lead to the erosion of trust-based bonds between grantees and beneficiaries. This makes it impossible for grantees to nudge the work of beneficiaries towards effective social change. There is really no substitute for field presence, even if limited, either for mentoring, monitoring, or gathering information on local context developments.” (Eaton 2021, May).

Creative Associates recruited “travelers” and “consultants” from at least 10 different countries in the Americas and Europe to take part in its Cuba project from 2008 to 2012. A review of confidential monthly reports filed by the company show that projects and people were identified by code. One report stated:

- FO7 has been fully prepared to travel by CREA-CR staff. He will search for networking opportunities among hurricane victims, rural groups, and victims of economic discrimination.

- FO6 is successfully exploring youth networks in rural areas.

- Two grantee staff members will be attending a strategic planning and mapping session in Spain in July 2009. Work has also begun on the development of the leadership module that will be implemented with youth in Cuba.

Another report said:

- “In 2009, 77 travelers were on the ground in Cuba a total of 320 of the 365 days of the year.”

- Since beginning of program, more than $200,000 in material goods was given to project beneficiaries.

- “Our program assisted in the formation and development of an initiative seeking to establish bonds of collaboration and identity among cultural and community leaders. The project was created by a core of cultural promoters with a vision for a more participative society. A large number of cultural figures were enlisted to support the project.”

USAID now tells NGOs to avoid sending U.S. citizens to Cuba. “Special thought and consideration should be given to the selection of consultants and other individuals who may be required to travel to Cuba. It is preferable for these travelers to speak Spanish fluently, possess a solid understanding of the cultural context, and have prior experience on the island, in order to maximize their effectiveness in this unique operating environment.”

The Pan American Development Foundation hired subcontractors from Costa Rica, Mexico and other countries to avoid attracting the attention of Cuban intelligence agents. PADF trainers taught the subcontractors “how they could safely work in Cuba without getting into trouble or even placed in jail.” (Eaton 2019, August).

Former PADF director John Sanbrailo explained, “What PADF has been doing, largely with USAID and State Department grants, is building grassroots democracy and nurturing the emergence of independent civil society. We saw our strategy as preparing the groundwork for a democratic transition that might follow after the passing of the Castro brothers and when the Cuban people are able to demand more freedom. This was PADF’s historic role and the very reason it was created — to empower citizen groups and the private sector to play a more significant part in the development of their countries.”

Where the Money Goes

Cuba program disbursements in the USG dataset totaled $218,367,438 from 2001 to 2021. That included $125,986,260 to support democratic participation and civil society; $35,714,592 for human rights programs; and $25,078,917 for media and free flow of information. (Eaton 2021, Data 3).

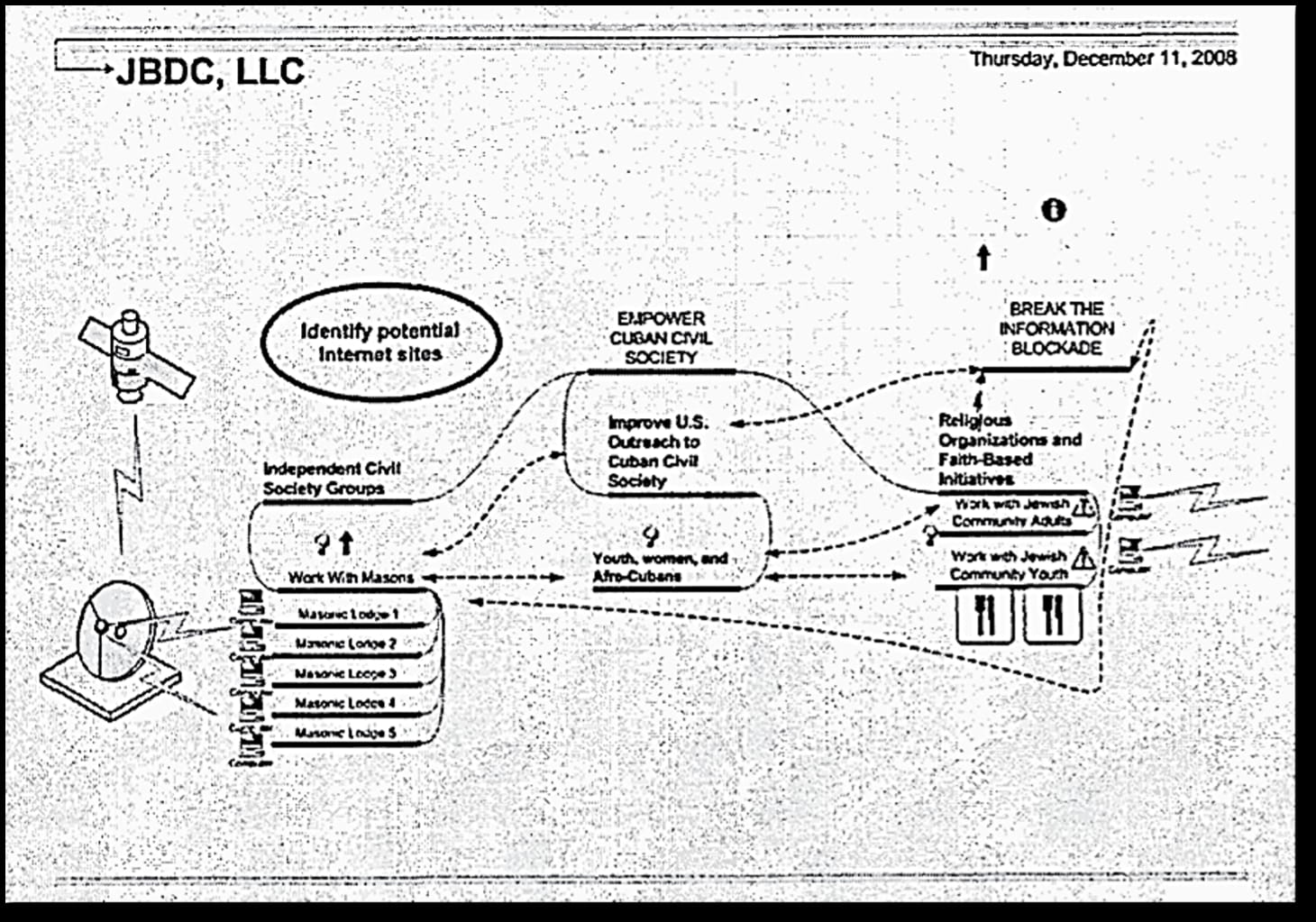

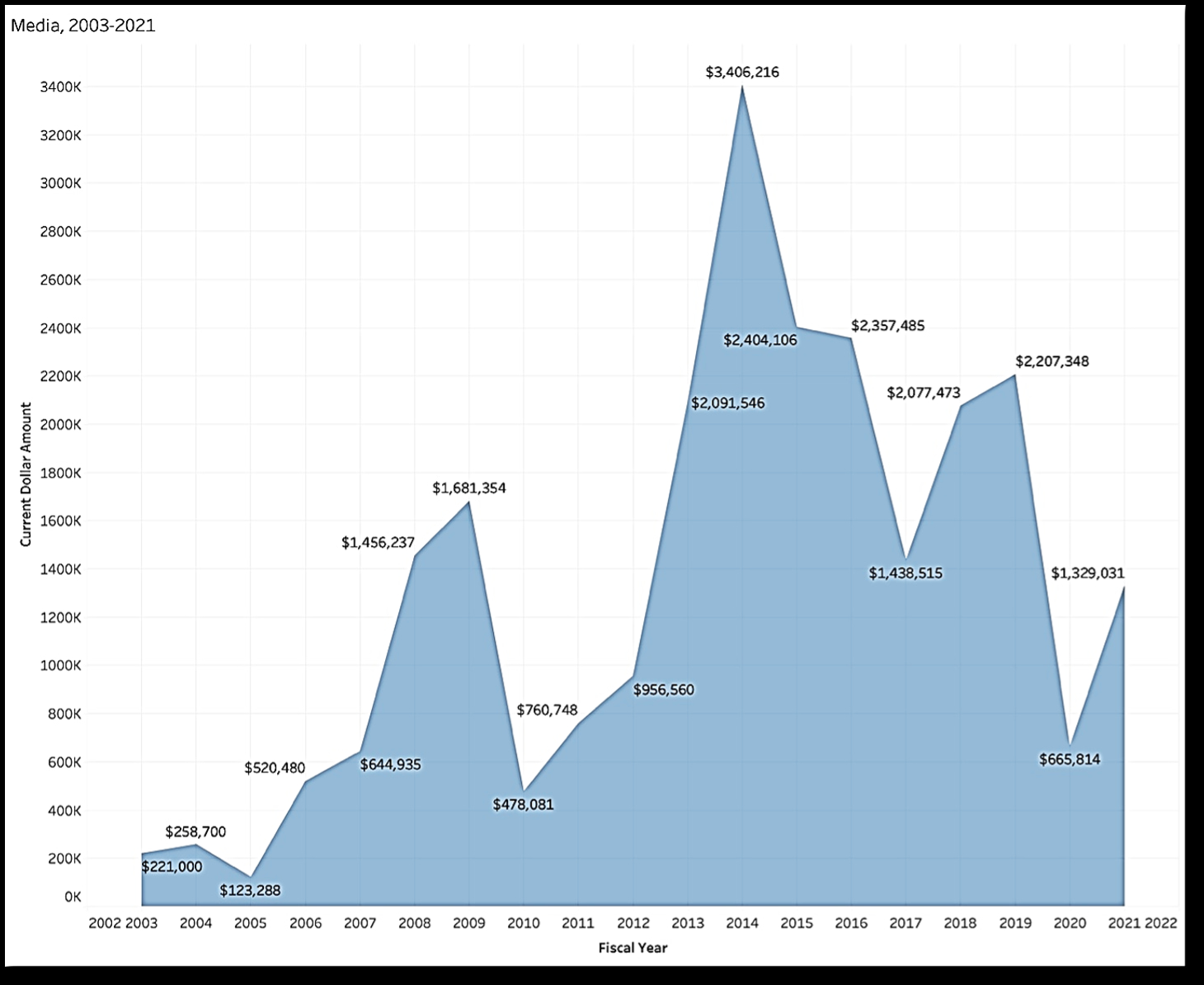

Grants awarded each year to fund “media and the free flow of information” in Cuba increased by 166% from 2003 to 2021, from $5,384,075 during the years 2003-2010 to $19,694,842 during 2011-2021. The total for 2003-2021 was $25,078,917. (Figure 4). (Eaton 2021, Data 4).

Figure 4 - Spending for media-related projects totaled $25,078,917.

The top four named recipients of media and free flow of information projects were the Cuban Democratic Directorate, the New America Foundation, International Republican Institute, CubaNet and People in Need. (Eaton 2021, Data 5). The National Endowment for Democracy, or NED, managed media projects worth $15,567,694. That was 62% of the total.

The NED

A 2010 lawsuit against the NED discusses the organization’s controversial history. Lawyers wrote: “NED acknowledged that it is and was exercising a traditional governmental CIA (Central Intelligence Agency) function. When it was revealed in the late 1960’s that some American private volunteer organizations were receiving covert funding from the CIA to wage the battle of ideas at international forums, the Johnson Administration concluded that such funding should cease, and recommended the establishment of ‘a public-private mechanism’ to fund overseas activities openly. Accordingly NED was established.” (Milner 2010).

A Sept. 30, 1993, speech by sociology professor William Robinson contends that NED is “closer to clandestine national security organs such as the CIA than to the apolitical or humanitarian endowments its name would suggest.” (Eaton 2020). Robinson said, “The name ‘National Endowment for Democracy’ is a misnomer, and a deliberate one. It conjures up an apolitical and benevolent image, such as that enjoyed by the National Endowment for the Arts or other humanitarian societies. In fact, the NED was created at the highest echelons of the US national security state, as part of the same project that led to the illegal operations of the Iran-contra scandal. The NED grew out of Project Democracy, a secret program launched by the Reagan administration in 1981 under the auspices of the National Security Council. “The NED claims to conduct its activities publicly, above board. In practice, the NED operates as a semi clandestine and highly secretive organization. … NED officials operate more often in the shadows than in the open, much like an agency dedicated to covert operations. The NED functions through a complex system of intermediaries in which operative aspects, control relationships, and funding trails are nearly impossible to follow and final recipients are difficult to identify.”

NED is more transparent today than in decades past and publishes the names of grant recipients each year. A sampling of the group’s program goals are below. (Eaton 2019, March).

- To empower Cuban artists as cultural leaders to promote citizen participation and social change in society.

- To strengthen the leadership and organizational skills of particularly disenfranchised groups in Cuba.

- To support and integrate young Cuban journalists into a regional network of digital media initiatives throughout Latin America.

- To fight impunity against human rights violations and to raise awareness about social conflicts in Cuba.

- To promote public debate about a democratic transition in Cuba.

- To strengthen access to information and enhance critical thinking in Cuba.

- To strengthen the capacity of Cuban civil society activists to promote democratic and pluralistic elections.

- To strengthen the capacity of independent civic centers and initiatives in Cuba to promote democratic ideas and values.

- To enhance civil society’s understanding and capacity to propose political alternatives.

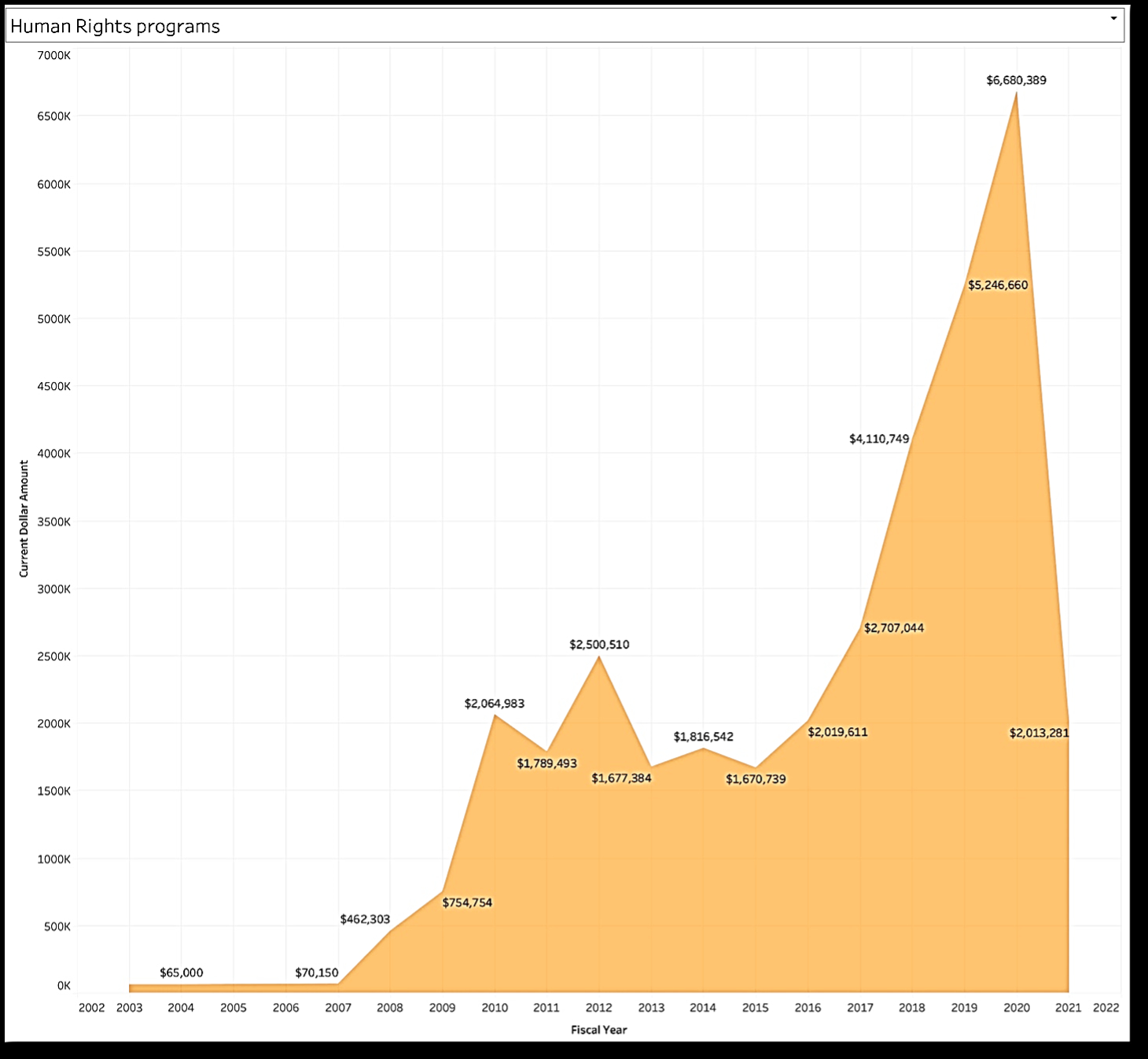

Funding specifically aimed at increasing human rights in Cuba rose during the Trump administration, hitting a high of $6,680,389 in 2020, the single highest yearly total recorded over the past two decades. (Figure 5).

Figure 5 - Spending for human rights programs reached a high mark in 2020.

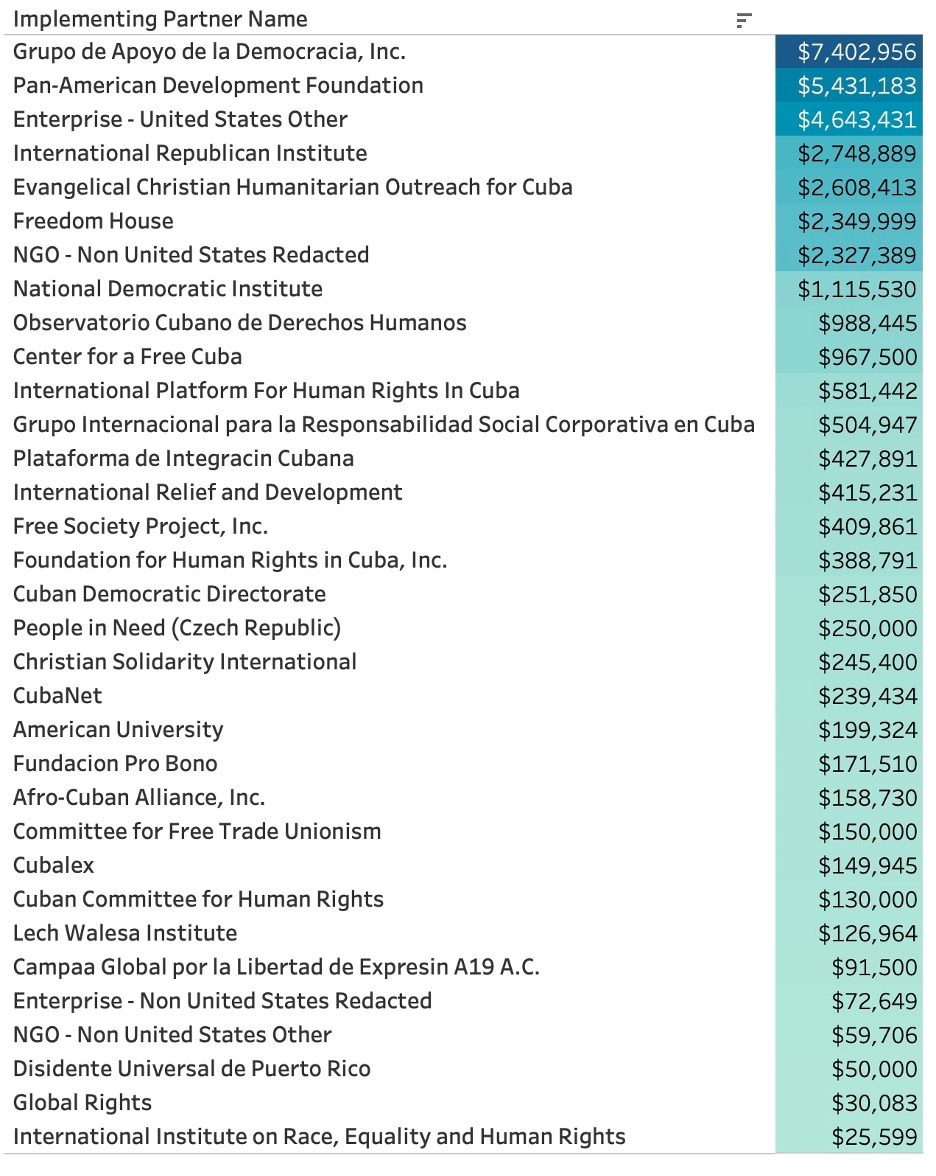

The top five named recipients of funds for human rights programs were Grupo de Apoyo a la Democracia, with $7,402,956; Pan-American Development Foundation, $5,431,183; International Republican Institute, $2,748,899; Evangelical Christian Humanitarian Outreach, $2,608,413; and Freedom House, $2,349,999.

The full list is below. (Figure 6).

Figure 6 - The total spent for human rights programs was $35,714,592.

Funds for democratic participation and civil society peaked in 2010 (Eaton 2021, Data 6). Many programs active that year began during the George W. Bush administration. Congressional funding approved for Cuba programs reached a high during the Bush administration, hitting $45.7 million in 2008. (Sullivan 2008). One of the most controversial programs was a Twitter-like project operated by USAID’s Office of Transition Initiatives, or OTI.

OTI

A Congressional Research Service report described OTI as follows, “Unlike its counterparts at USAID, its mission is neither humanitarian nor development-oriented. OTI’s activities are overtly political, based on the idea that in the midst of political crisis and instability abroad there are local agents of change whose efforts, when supported by timely and creative U.S. assistance, can tip the balance toward peaceful and democratic outcomes that advance U.S. foreign policy objectives.” (Lawson 2009).

OTI director Robert Jenkins stated, “It’s simple; we try to change the world. …we start with, ‘Our mission is to advance U.S. foreign policy.’ Our unofficial mission statement is, ‘OTI makes a critical difference in the most critical places at the most critical times.’ Our job is to assault the impossible to make it possible and then consider it achieved. Our job is to go into the darkest places and shed some light. Our job is to find places that need hope and provide it. Our job is to provide time when time is needed, but it’s a very short commodity.” (Jenkins 2012)

After Fidel Castro stepped down in 2008, OTI saw a window of opportunity in Cuba. The agency gave Creative Associates International a 3-year contract worth up to $15.5 million to set up a base in Costa Rica and run a Cuba program designed to “help create positive enabling environments for change in advance of, during, and, as needed, immediately following a transition.” (OTI 2008).

OTI’s Cuba program “awarded 103 grants, 12 of which made up a Twitter-like project eventually called ZunZuneo.” In April 2014, the Associated Press published a report questioning the legality of the project. Some members of Congress questioned USAID about ZunZuneo’s “aura of secrecy and covertness.” USAID said the project wasn’t covert, but was carried out “discreetly.”

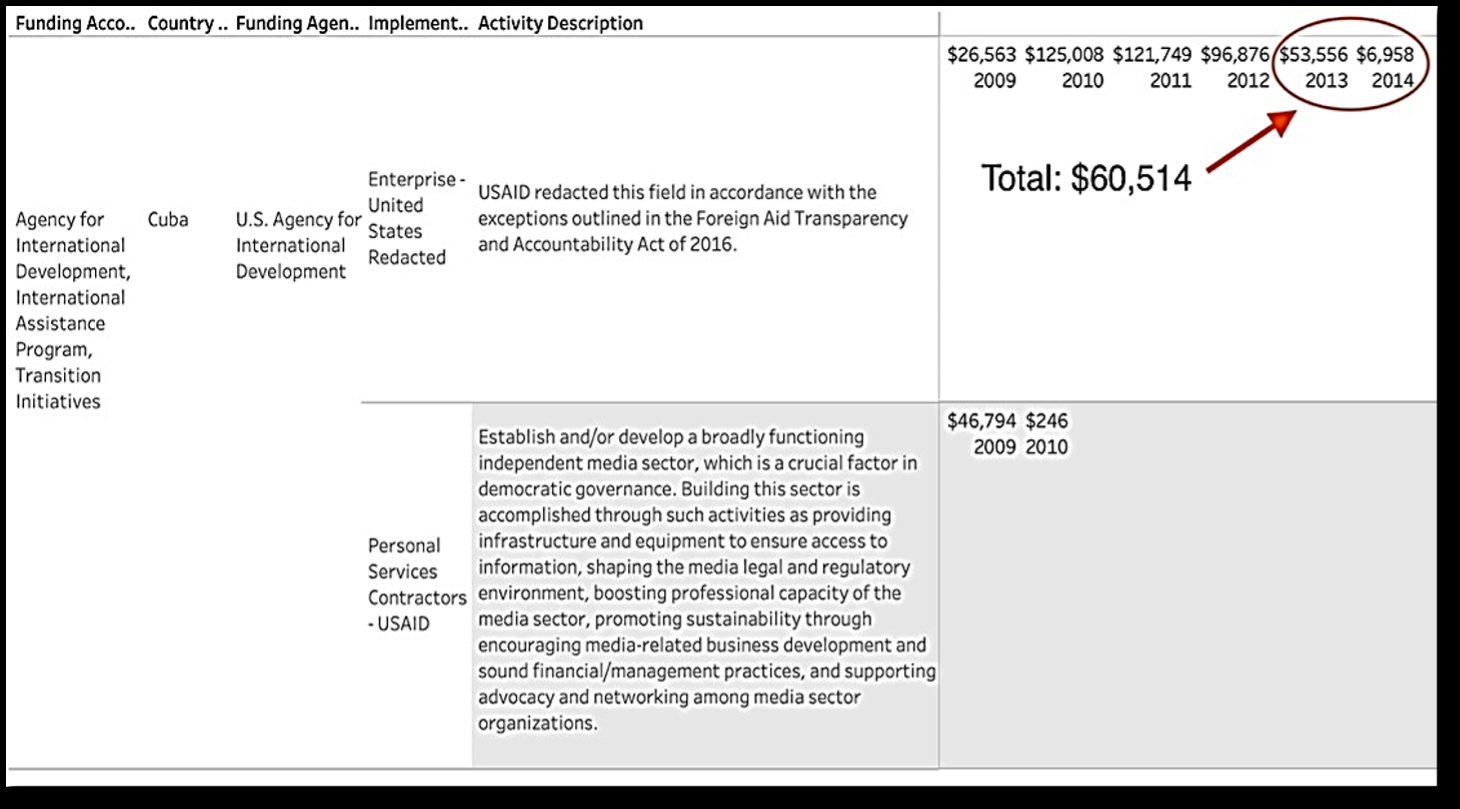

Creative Associates, worried that the Cuban government would discover U.S. government ties to ZunZuneo, “took action to conceal the origin of funds and ownership of the platform,” USAID’s Office of Inspector General said in a report critical of the agency. (USAID 2015). The contractor said it couldn’t find a way to make ZunZuneo self-sustaining and ended it in August 2012. The OIG stated, “Although we did not find any evidence of fraud, the methods designed to conceal funding sources and recipients pose inherent risks.” USAID’s website states that OTI ended the program in 2012. (USAID 2021, September). The USG dataset shows OTI continued spending money, shelling out $60,514 in 2013 and 2014. (Figure 7).

Figure 7 - USAID redacted the description of payments made in 2013-14.

Transparency

USAID, the State Department and NED all report funding “undisclosed” or “miscellaneous” contractors whose names aren’t revealed. Subcontractors are another unknown. Some NGOs receive grants of $1 million and up and routinely hire subcontractors, but their names are not made public.

The democracy programs are against the law in Cuba. U.S. officials say they don’t reveal details to protect participants from reprisals. Democracy-building strategies are also considered “trade secrets” and are exempt from disclosure under the FOIA, officials say.

Agencies make some redactions under the Foreign Aid Transparency and Accountability Act of 2016, which states:

“If the head of a Federal department or agency, in consultation with the Secretary of State, makes a determination that the inclusion of a required item of information online would jeopardize the health or security of an implementing partner or program beneficiary or would require the release of proprietary information of an implementing partner or program beneficiary, the head of the Federal department or agency shall provide such determination in writing to the appropriate congressional committees, including the basis for such determination.”

The 2016 law also allows redactions if disclosure online “would be detrimental to the national interests of the United States.”

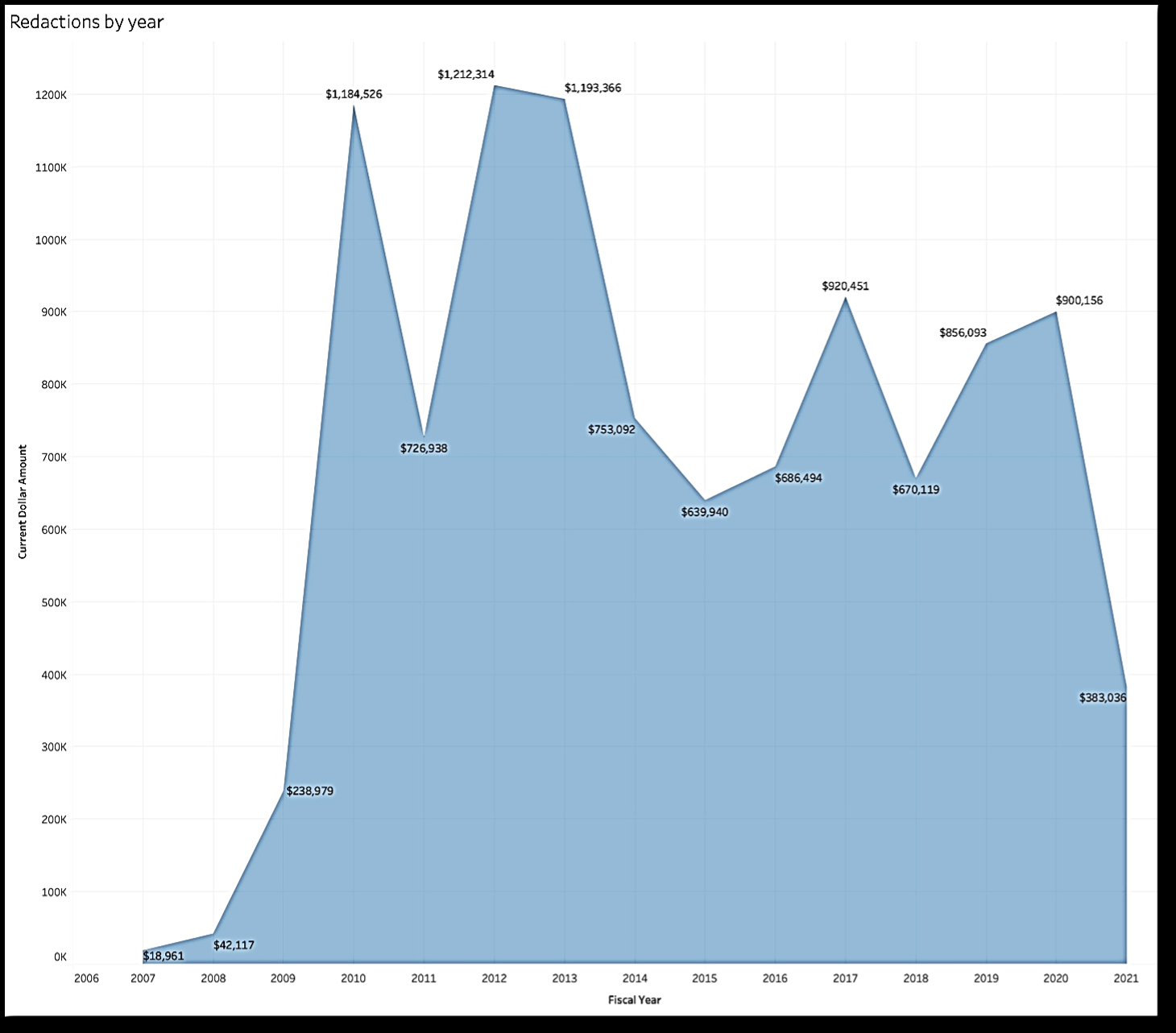

Information about disbursements totaling $10,426,582 was redacted under the 2016 law. (Figure 8). That amount included redactions for $6,696,727 in money spent before the law took effect. (Eaton 2021, Data 7).

Figure 8 – Information about more than $10 million in spending was redacted from 2007 to 2021.

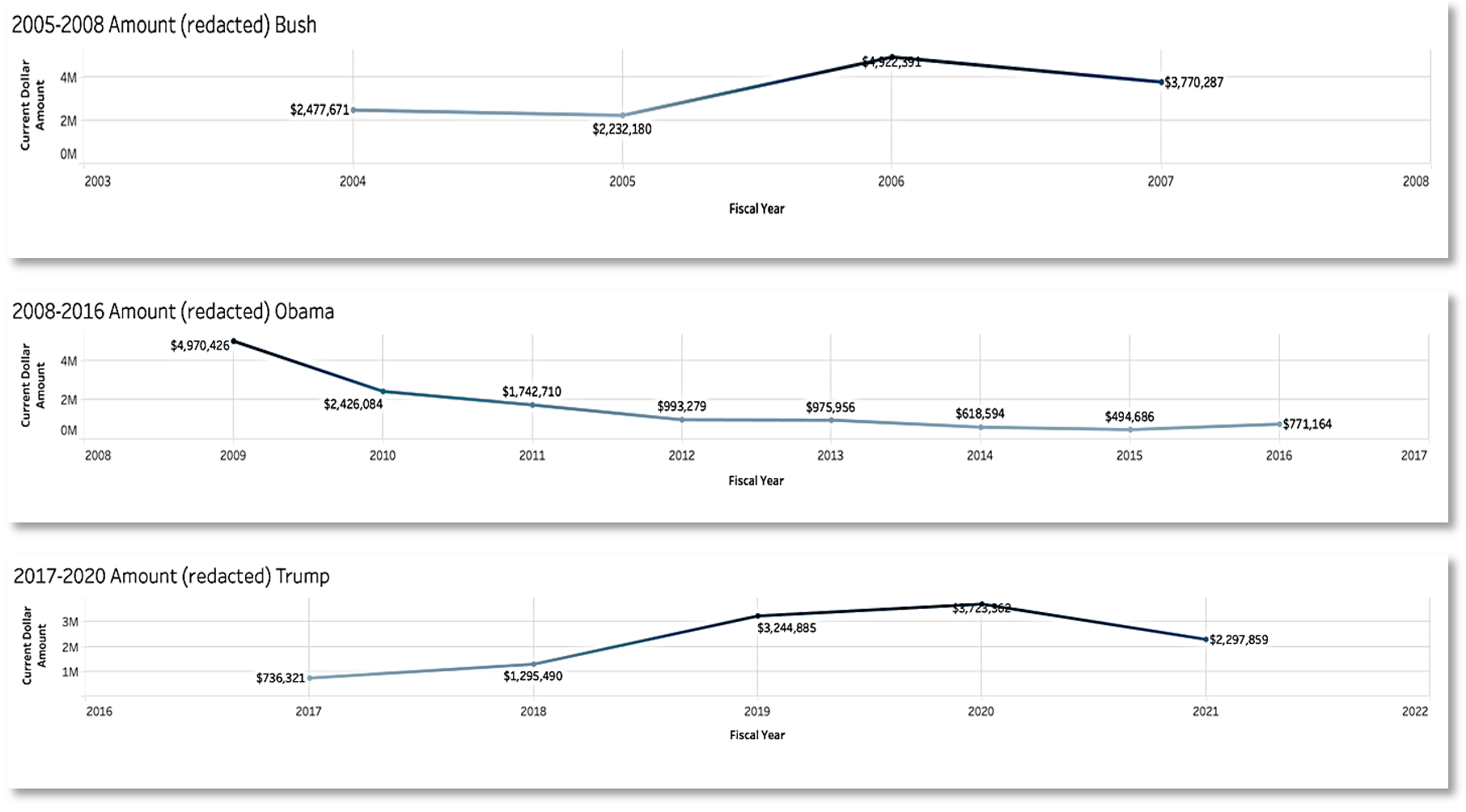

Funds for programs that are redacted or undisclosed jumped by 74% under Donald Trump as compared to the Obama administration. The total dollar amount for redacted or undisclosed programs in the USG dataset was $48,121,849 or 22% of the total. Redactions under the George W. Bush administration totaled approximately $13,402,529; under Obama, $12,992,899; and under Trump, $11,297,917. (Figure 9).

Figure 9 – Average yearly dollar amount of redacted programs peaked at $3,350,632 under George W. Bush.

The NGO or government agency running a program is known as the “implementing partner” in government jargon. The partner showing the highest dollar amount in redacted expenses – at $19,902,017 – is listed as “Enterprise – United States Other,” a name that suggests the recipient is based in the U.S.

Redacted expenses in the “Enterprise – United States Other” category hit a high of $3,050,610 in 2020 before dropping to $2,079,930 in 2021. (Eaton 2021, Data 8). Tucked away in the activity names and descriptions in the spending record are the names of several important grantees, including Bacardi Family Foundation, shown as having received $1,886,681; Canyon Communications, $1,790,000, and the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, $538,188.

It’s unclear why spending records do not more readily disclose these recipients. Some of these disbursements may be more political in nature than others, or perhaps officials are trying to protect recipients from unwanted scrutiny.

In 2014, Jeff Kline of Canyon Communications drew controversy over a radio contest aimed at Cuban youth. He traveled to Cuba and told young people that those producing the best radio programs would receive "netbooks, digital recorders, radio production equipment and other equipment to produce independent programs." One participant said she produced a radio segment, but the contest abruptly ended and no one ever received prizes or explained what went wrong. The woman said, “I feel used. They tried to manipulate me.” (Eaton 2014).

July 11 protests in Cuba

Spending records show that USAID and the State Department have increased funding for human rights and media-related programs in Cuba in recent years. The dollar amount spent for projects that are undisclosed or whose descriptions are redacted has also climbed. Democracy-promotion efforts intensified under the Trump administration, but I have not found any evidence directly linking recent spending patterns to the July 11 protests.

Journalist Alan Macleod contends that USAID’s efforts to enlist Cuban musicians and others to bring about social change may be a sign that the agency played a role in the protests. He wrote, “The U.S. establishment immediately hailed the events, putting its full weight behind the protesters. Yet documents suggest that Washington might be more involved in the events than it cares to publicly divulge.” (MacLeod 2021).

In June 2021, USAID offered $2 million for programs designed to “advance the effectiveness of independent civil society groups to advocate for greater human rights and freedoms.” The agency’s Notice of Funding Opportunity stated, “The past several months have served as a watershed moment for Cubans demanding greater democratic freedoms and respect for human rights. Artists and musicians have taken to the streets to protest government repression, producing anthems such as “Patria y Vida,” which has not only brought greater global awareness to the plight of the Cuban people but also served as a rallying cry for change on the island.” (USAID 2021, June).

The notice expressed interest in a range of project proposals, including those that would strengthen and promote “the creation of issue-based and cross-sectoral networks to support marginalized and vulnerable populations, including but not limited to youth, women, LGBTQI+, religious leaders, artists, musicians, and individuals of Afro-Cuban descent.”

The $2 million program could not have played a role in the July demonstrations because USAID was still accepting applications when the protests occurred. But it’s clear that U.S. democracy programs have been sowing the seeds of opposition for decades.

If there were any signs of the impending protest in U.S. government spending records, it would be a security lapse. USAID and the State Department closely guard details of their Cuba projects. If U.S. agencies did not play some kind of role in the protests, it would be a failure of sorts because they have been trying for decades to provoke an uprising against the socialist government.

No doubt, the fact that thousands of Cubans took to the streets shows that decades-long U.S. economic sanctions, which intensified under President Trump, have taken a toll. Cuban President Miguel Díaz-Canel acknowledged so much after the protests erupted, saying his government had been trying to keep the economy functioning “in the face of a policy of economic asphyxiation intended to provoke a social uprising.” (Marsh 2021, July).

Some activists believe the U.S. should step up its efforts to support the democracy movement in Cuba because they believe the socialist government is weak. Others disagree. “Trump’s policy of hostility and confrontation made the human rights situation in Cuba worse not better. It aggravated the regime’s siege mentality, gave it an excuse to crackdown on dissidents and other independent voices, and provided a convenient scapegoat for Cuba’s worsening economy.” (CDA 2020).

Secrecy surrounding the work of U.S. agencies and their partners makes it difficult to know what they do in Cuba and whether they are effective. Some analysts believe U.S. government-financed NGOs used the hashtag #SOSCuba to help organize and spread the July street protests. While going through spending records, I didn’t see any references to the #SOSCuba campaign. It defies logic to think that all those who protested on July 11 are on the U.S. government payroll. Many Cubans told journalists they took part because they were angry, desperate and poor.

El Estornudo, an online news site in Cuba, reported that San Antonio de los Baños near Havana appeared to be the epicenter of the protests. (Colomé 2021). On July 10, the site said a Facebook group for residents in town asked, “Tired of having no electricity? Fed up of having to listen to the imprudence of a government that doesn’t care about you? It’s time to go out and to make demands. Don’t criticize at home: let’s make them listen to us.” Thousands of the town’s residents marched the next day. (Marsh 2021, August).

Such accounts are invaluable in understanding what led to the July 11 protests. Poring over incomplete, imperfect spending records looking for clues can’t replace reporting on the ground.

Someday, government documents may reveal what role USAID and the State Department played – or didn’t play – in the historic protests. But researchers can’t count on any quick answers, particularly if they rely solely on Freedom of Information Act requests.

In January, I pleaded with the State Department not to terminate a FOIA request I filed on Oct. 8, 2011. I followed up on Sept. 4, 2021, asking for an update. The agency replied that they expect to process my decade-old request by the year’s end.

Notes

[i] Sources: This paper is based primarily on public records. No single government website shows all U.S.-financed Cuba projects. The latest complete ForeignAssistance.gov dataset contains $776,057,578,886 in State Department and USAID disbursements worldwide from 2001 to 2021. (ForeignAssistance.gov. 2021). This dataset has limitations, but is the largest single representative data sample I have found. I will cite it as “USG dataset.” (Figure 1).

[ii] I use the term “democracy promotion” to refer to projects U.S. government agencies carry out in Cuba. Some critics call these as “regime change” or “subversion” programs. I prefer more neutral language, reflecting the fact that I am not taking sides in the long-running U.S.-Cuba fight, and am merely trying to better understand U.S. government activities.

References

CANF. “Findings and Recommendations on the Most Effective Use of USAID-Cuba Funds Authorized by Section 109(a) of the Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity (Helms-Burton) Act of 1996.” Cuban American National Foundation, March 2008.

CDA. “The United States and Cuba: A New Policy of Engagement.” Center for Democracy in the Americas and the Washington Office on Latin America, December 2020.

Colomé, Carla Gloria. “11 de julio en San Antonio de los Baños: Lo que se ve/lo que no se ve.” El Estornudo, July 22, 2021.

Eaton, Tracey. Data 1. USG dataset. Eaton 2021, Data 1; Data 2. Funds for universities. Eaton 2021, Data 2; Data 3. Program purpose, by year. Eaton 2021, Data 3; Data 4. Media and free flow of information. Eaton 2021, Data 4; Data 5. Media projects, by partner. Eaton 2021, Data 5; Data 6. Program purpose, 2001-2021. Eaton 2021, Data 6; Data 7. Undisclosed activities, by year. Eaton 2021, Data 7; Data 8. Undisclosed activities, by partner. Eaton 2021, Data 8. (See all eight interactive data visualizations here).

______. “Taxpayer-funded contest aborted.” Along the Malecón, Oct. 11, 2014.

______. “NED details $4.6 million in Cuba grants.” Cuba Money Project, March 3, 2019.

______. “Low-key foundation reveals approach in Cuba.” Cuba Money Project, Aug. 18, 2019.

______. “Exploring the roots of the NED.” Cuba Money Project, Jan. 24, 2020.

______. “USAID in Cuba: Code names and counter surveillance.” Cuba Money Project, May 10, 2021.

Federal Register. “Strengthening the Policy of the United States Toward Cuba.” National Archives and Records Administration, Oct. 20, 2017.

ForeignAssistance.gov. Complete USG dataset. Last updated July 26, 2021. https://foreignassistance.gov/data. Download file here (2.4GB).

Gross, Alan. “Affidavit of Alan Gross.” United States District Court for the District of Columbia, March 7, 2013.

Jenkins, Rob. SWIFT IV Pre-Solicitation Conference. Transcript of conference with prospective partners interested in working with the Office of Transition Initiatives. U.S. Agency for International Development, June 20, 2012.

Lawson, Marian Leonardo. “USAID’s Office of Transition Initiatives After 15 Years: Issues for Congress.” Congressional Research Service, May 27, 2009.

Macleod, Alan. “The Bay of Tweets: Documents Point to US Hand in Cuba Protests.” MintPress News, July 16, 2021.

Marsh, Sarah. “Cuba arrests activists as government blames unrest on U.S. interference.” Reuters, July 12, 2021.

Marsh, Sarah. “The Facebook group that staged first in Cuba's wave of protests.” Reuters, Aug. 9, 2021.

Milner, Julie. Zhi Guo vs. NED and others. U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, Aug. 30, 2010.

Soler, Marga Gual. “Diplomacia Científica en América Latina y el Caribe.” United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2020.

State Department. “Notice of Funding Opportunity: Cuba Proposals.” Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, May 2020.

Sullivan, Mark. 2008. “Cuba: Issues for the 110th Congress.” Congressional Research Service, Sept. 24, 2008.

Transition Initiatives, Office of. Attachment I SOW (Statement of Work). U.S. Agency for International Development, 2008 (not dated).

USAID, n.d. CNECT Program proposal. U.S. Agency for International Development, not dated, likely 2009-10.

USAID 2015. “Review of USAID’s Cuban Civil Society Support Program.” Office of Inspector General, Dec. 22, 2015.

USAID 2019. “Promoting Human Rights in Cuba.” USAID, June 27, 2019.

USAID 2020. “Request for Applications for Exposing Exploitation in Cuba.” Office of Acquisition & Assistance, August 2020.

USAID 2021, June. “Notice of Funding Opportunity. Supporting Local Civil Society and Human Rights in Cuba.” U.S. Agency for International Development, June 30, 2021.

USAID 2021, September. “Cuba – Political Transition Initiatives.” U.S. Agency for International Development, webpage captured Sept. 11, 2021.