As an undergraduate at Harvard in the mid-1980s, Kathy Kleiman was the only woman in most of her upper-level computer science classes. One by one, the female students by her side in lower-level classes had dropped out of the field. Kleiman felt frustrated, alone, and in need of role models. She began to wonder whether women computer scientists had come before her. Was this an untrodden road she was walking?

Kleiman—now a senior fellow at AU’s Washington College of Law—started visiting the library in her free time, paging through books about the history of computing in search of women. As she perused the historical volumes, her interest was piqued by a four-decades-old black-and-white photograph.

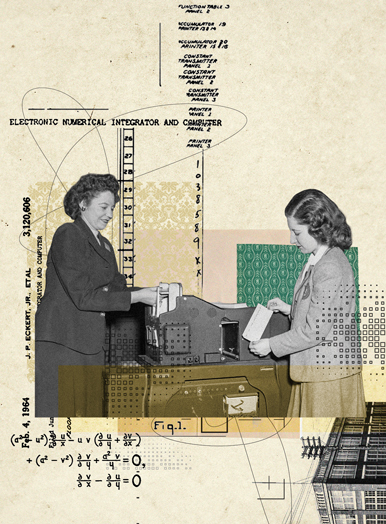

In 1945, engineers at the University of Pennsylvania, under a contract for the United States Army, had finished the development of the first general purpose, programmable, all-electric computer, known as Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer, or ENIAC. It was originally built to calculate the projectiles of ballistic missiles during World War II. The photo that caught Kleiman’s attention showed two women standing in the midst of the room-sized ENIAC in the days before its public unveiling. The caption didn’t name the women, so Kleiman reached out to a historian for more information—she replied that the women were probably models, or “refrigerator ladies,” hired to pose with the computer.

Kleiman’s gut instinct told her that the historian was wrong. Both women looked comfortable with the gargantuan piece of equipment, their arms reaching toward knobs and dials to adjust settings. So Kleiman delved into the history of ENIAC—first reading about it, and then interviewing people involved in the project.

The women, it turned out, were Jean Jennings Bartik and Frances “Fran” Bilas Spence, two of the six women who led the daunting task of programming ENIAC. The other four: Kathleen “Kay” McNulty Mauchly Antonelli, Frances Elizabeth “Betty” Snyder Holberton, Marlyn Wescoff Meltzer, and Ruth Lichterman Teitelbaum. Together, the women had spent months—without computer manuals or programming languages—figuring out how to program this first modern computer to solve differential calculus equations.

There were indeed many women that came before her, Kleiman had discovered, but their stories had never been told.

Kleiman wrote her undergraduate thesis on the female programmers, dubbed the “ENIAC Six,” who had been ignored by history books and omitted from photo captions for decades. The history of computer science, her thesis argued, had long revolved around the history of hardware—the tales of men building big physical machines. Historians had ignored the stories behind the software and the programmers—who included women like the ENIAC Six. Kleiman wanted to change that.

Over the coming years, she spoke with the women, recording their stories for an oral history. She lobbied to include them in the ENIAC 50th anniversary event in 1996 and nominated them for awards and accolades.

“These women became my friends, they became my mentors, they became my role models,” Kleiman says. “It seemed so unfair that they had not been credited or honored. They helped create the world we live in—the computer age, the information age.”

Kleiman learned how the diverse group of women, and dozens of other female math majors from around the country, had been recruited by the Army during World War II when male mathematicians were on other projects, including Los Alamos. The women learned how to calculate artillery trajectories by hand—complex computations that took days to complete. To speed the process, the Army commissioned work on the computer, and when the experimental hardware actually worked, the ENIAC Six were asked to teach themselves how to use it and write a program that to automate the trajectory calculations they’d grown so familiar with.

At the same time she was devoting her free time to the ENIAC Programmers Project, Kleiman was also forging ahead with a burgeoning law career. She had merged her interests in law and computer science to become one of the first lawyers specializing in internet law and policy. She was leading the field with new cases, ideas, and procedures but often, she was still the only female in the room. Her conversations with the ENIAC Six helped make this path easier and less lonely, she says.

“I’m not sure I would have stayed in computer science if I hadn’t found this story,” Kleiman says. “And then, when I was one of the first lawyers working in internet law, every room I walked into was all male. I would sometimes call the ENIAC programmers and talk to them about that experience; they got it.”

Kleiman went on to record extensive oral histories of the women, assemble a website and, in 2013, release an award-winning 20-minute documentary, The Computers, in collaboration with producers from both PBS and Frontline. At screenings of the film held at universities, film festivals, and tech companies around the world, Kleiman witnessed firsthand the emotional response that people—especially women students and technologists—had to the story of the ENIAC Six.

“[It] really touches people,” Kleiman says. “These women were doing critically important and exciting work, and what they were able to accomplish is inspiring.”

But the documentary also drew critics—historians who didn’t think Kleiman had her facts straight, or thought she was rewriting history and exaggerating the role of the ENIAC Six. Those naysayers are what drove Kleiman to write a book, as a way to set the record straight and lay out the detailed facts she’d collected over three decades of research.

When COVID-19 shut down classrooms and offices at AU, Kleiman saw her chance.

“The libraries were closed, the archives were closed, but I had decades of research—tens of thousands of pages of material—already collected,” she says. “I literally organized it on the floor of an entire room of my house and started sorting it.”

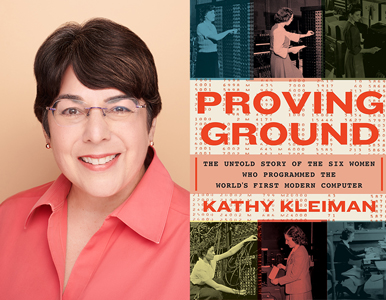

That research paid off. In July 2022, her book, Proving Ground: The Untold Story of the Women Who Programmed the World’s First Modern Computer, was published. Often compared to Hidden Figures by reviewers, the book weaves the history of the ENIAC with the personal narratives of the programmers and their vital roles in the development and use of the computer.

When she first stumbled upon the story of the ENIAC Six, Kleiman wasn’t looking for a passion project that would span so many years or searching for a topic for a book. But as science, technology, engineering, and math fields still struggle with diversity—women make up only 28 percent of the STEM workforce, according to a 2020 report from the American Association of University Women—Kleiman thinks it’s important for people to hear these kinds of success stories.

“For every generation of women to feel like they’re the first in computer science is unfair and unjust,” she says.

That spirit is part of why Kleiman is also an outspoken supporter of AU’s new Inclusive Tech Policy (ITP) group, a cross-campus initiative that focuses on advancing underrepresented voices in global technology policy. At the first event held by the group, on a dreary evening in October, Kleiman discussed her book and—thanks to a generous donor—gave away free copies to eager students.

“It was just an incredible experience to see the turnout in the middle of this cold rainy week and tell this story of women in STEM to a group of young women and men who want to go into this field,” she says. “STEM and STEM policy are better when we have diverse voices in the room.”

“We were especially excited to highlight Professor Kleiman’s work as it shines a light on the historical role of women in computing,” adds Diane Burley, vice provost of research and ITP member. “Inclusion requires a sense of belonging, and knowing this history shows us that we belong.”

Even with the publication of Proving Ground, Kleiman says her changemaking work is not done. There are thousands more stories of innovative women in STEM and computer science that remain untold.

“I hope we tell more of [them],” she says. “If we want diversity in STEM, we need to inspire the pipeline of students who are learning about these topics.”

When female computer scientists struggle to see faces like theirs in a classroom or meeting room, perhaps today, thanks to Kleiman and Proving Ground, they will have an easier time finding role models on library shelves than she did.

Excerpt from Proving Ground: The Untold Story of the Women Who Programmed the World’s First Modern Computer by Kathy Kleiman

On a cloudy day on Tuesday, June 2, 1942, Kathleen “Kay” McNulty,

twenty-one years old, smiled and took her bachelor’s in mathematics diploma from Reverend Hugh L. Lamb, Auxiliary Bishop of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia. She had dancing eyes, a narrow face, and dimples. It was commencement at Chestnut Hill College, a Catholic women’s school in the northwestern edge of Philadelphia, overlooking the Wissahickon Creek. Kay was one of 107 graduates.

The commencement was outside, near the tennis courts, and the principal address was also delivered by Bishop James Kearney of Rochester. One of Kay’s best friends, Frances “Fran” Bilas (pronounced BEE-las) received many awards that day, including one from the National Catholic School Press Association, the Student Teacher’s Gold Key Award, and a Kappa Gamma Pi certificate “for graduation with distinction and leadership in extra-curricular activities.” Kay knew Fran was one of the smartest students in the class. As Kay and Fran met their families, clutching their degrees in their hands, both of them knew that they were starting the next chapters of their lives.

It was a strange time to be a young American entering the job market. At the University of Pennsylvania commencement exercises, which took place the same day, seventy-three degrees were awarded in absentia to young men who had already joined the armed services.

The Philadelphia Inquirer might have been addressing Fran and Kay with the headline it ran above photos of different area commencements: STUDENTS GRADUATING INTO WORLD AT WAR.

The Women’s Undergraduate Record, the yearbook for women at the University of Pennsylvania for 1941, declared that the war was: "a great sorrow to the world . . . Even though we were not actively engaged in it, it is a war world in which we live. We cannot isolate our sympathies, even though we may hope to isolate our nation. Our eyes are on Europe and her guns strike our hearts. The maturity of Seniority has been accepted by the sober thoughts that are with us all."

Kay and Fran had been two of only three math majors in their class at Chestnut Hill College; the third, Josephine Benson, was also their best friend. Kay had picked math because it was easy and fun for her. A few days into college, an adviser asked her to pick a major, telling her to choose the subject she liked best. “Mathematics,” she immediately responded. For her, math was “no work. It was a no brain thing for me. It was just like a wonderful puzzle that you could do and there was always an answer.”

Most women who entered Chestnut Hill College during the Depression majored in home economics, the study of life skills such as cooking, sewing, and finance. In fact, just a few weeks before Kay, Fran, and Josephine’s commencement, Chestnut Hill’s home economics department presented a fashion show in the school auditorium. A hundred gowns were modeled by students, with a patriotic theme, due to the war. Many young women in Kay’s class wanted to be dietitians in schools or hospitals. Then they would marry and have children. Home economics could help them in the dietitian field, but that wasn’t the point; they had to learn how to cook and run a household well if they were going to be good housewives.

Kay was not like many of the other students. She wanted to do something important, and eventually she wanted to start a family. And she did not think the two were mutually exclusive.

Not two weeks after she graduated, she spotted a notice in Philadelphia’s Evening Bulletin: LOOKING FOR WOMEN MATH MAJORS. The Army sought women to work at the University of Pennsylvania’s Moore School of Electrical Engineering. She didn’t know what the job was but thought it amazing that a job for women with degrees in mathematics “would be advertised in the paper.” Before the war, this would have been unheard of; ads for math-related positions (such as accountants and actuaries) were in the “Male Help Wanted” section of the newspaper. Math was a man’s job. In the “Female Help Wanted” sections, there were jobs for secretaries, nutritionists, nannies, and laundresses. Those interested in the Moore School opportunity were to report to a recruiting office on South Broad Street in South Philadelphia, inside the Union League, a storied private club that also contained offices. Kay called Fran and Josephine and said they should all interview together.

But Josephine already had a job. And so the next day, Kay showed up with only one best friend, not two.

All over the country, American women were seeing notices telling them they were needed for war work. Many of these ads were for industrial positions. With brothers, cousins, uncles, and fathers volunteering for service and being drafted, the government and military began a deliberate strategy to recruit women into factories and farms, for now-vacant positions.

During the Great Depression, it had been difficult for both men and women to obtain jobs. Unemployment soared to 24.9 percent in 1933 and remained above 14 percent from 1931 to 1940. During World War II, the government encouraged women to fill the jobs formerly open only to men—and women enthusiastically responded. From 1940 to 1945, the percentage of women in the workforce increased by 50 percent.

If the country were to clothe, feed, and provide guns, artillery, planes, and tanks to the armed forces, its women would have to take jobs in industrial manufacturing and in labor. The fictitious Rosie the Riveter, later the subject of a WE CAN DO IT! poster, was first introduced in a 1942 song that went, “All day long whether rain or shine / She’s a part of the assembly line / She’s making history, / working for victory.” Rosie had “a boyfriend, Charlie / Charlie he’s a Marine / Rosie is protecting Charlie / Working overtime on the riveting machine.” Posters recruiting women to war work trumpeted, “The more WOMEN at work the sooner we WIN!”

Millions of American women stepped up to the plate—taking on jobs making jeeps and tanks, sewing uniforms, canning food, making weapons and ammunition, and doing production for the wartime movies that kept the population (at home and overseas) entertained and diverted. Norman Rockwell’s Rosie the Riveter picture, featuring a young woman in blue overalls holding a sandwich in one hand with a rivet gun on her lap, and published on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post in May 1943, “proved hugely popular” and the Post loaned it to the US Treasury Department for war bond drives for the rest of the war.

Economic mobilization due to the war shifted many boundaries of traditional “men’s” and “women’s” work. Previously male-defined jobs such as building tanks and repairing airplanes were recast as feminine and glamorous, and women were welcomed—for the time being.

But separate from the boom in industrial employment, the war greatly expanded opportunities for college-educated women with backgrounds in engineering, science, and math. Women like Kay were seeing notices that seemed to be written just for them.

The Department of Labor’s Women’s Bureau proclaimed the new opportunities: [For] war job opportunities in science and engineering, you will find that the slogan there as elsewhere is “WOMEN WANTED!”

Women with math degrees were desirable assets who could help the Allies win the war.

Several months after Kay saw the ad in the Evening Bulletin, leaders of war industries and women’s college heads met at the Washington, DC, branch of the American Association of University Women to discuss steps that could speed the induction of college-trained women into specialized war jobs. During the conference, vice chairman of the War Production Board William Batt told the Philadelphia Inquirer, “Winning this war is a job of great magnitude and tremendous seriousness, and there is an appalling demand of everything an Army needs.” Women, he said, were demonstrating that “they can do as good a job as men, and in many instances a much better job in the factories and shops.” He said American women had not yet reached the pace of women in Russia and England in their war activity, but they could.

For decades, college-educated and highly skilled women had been

turned away from well-paying jobs despite their qualifications. Now they held no grudges and jumped into the workforce wherever they were needed.

When Kay and Fran went to the office inside the Union League, they were met by an Army recruiter who asked them about their math backgrounds right away: “Did you have differential calculus?”

“Yes,” Kay answered.

“Did you have physics?”

“Yes.”

“You are exactly what we need,” he said.

“They hired us on the spot,” Kay remembered.

She was happy; she had been out of college for only two weeks and she had a job—somewhat unusual for a graduate in any era, but even more unlikely given the circumstances. She and Fran were to report to the Moore School on July 1, 1942.

Copyright 2022 by First Byte Productions, LLC. Reprinted with permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.