In August 2021, Fatima* was an ordinary 14-year-old girl living in Afghanistan’s capital city of Kabul. The ninth grader studied math, science, history, writing, and art and dreamed of becoming a doctor. Then—following the sudden withdrawal of US and coalition forces—the Taliban swept through her country, and two decades of hard-won advancements for Afghanistan’s women and girls were erased overnight.

“People were terrified. They did not go out because they thought the Taliban would kill them,” Fatima says. “Everything closed for girls. They promised us they would open the doors of schools to us. But they did not.”

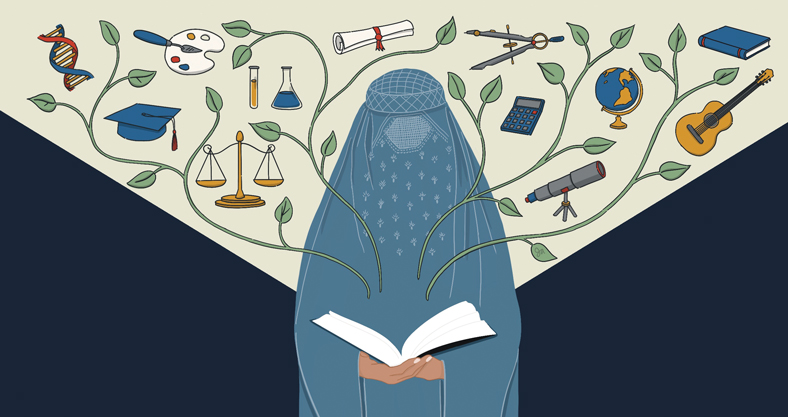

Under Taliban rule, Afghan girls are now prohibited from pursuing education past sixth grade, and women are banned from public and private universities and most jobs. They have no agency and no voice, political or otherwise. And since they cannot leave their homes without a male chaperone—to run around a playground, walk through a public park, or even visit a doctor or beauty salon—they spend most of their days hidden indoors.

“In no other country have women and girls so rapidly disappeared from all spheres of public life, nor are they as disadvantaged in every aspect of their lives,” wrote Richard Bennett, United Nations special rapporteur for Afghanistan, in September 2022. Bennett also expressed “grave concern about the staggering regression in women and girls’ enjoyment of civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights” under the Taliban.

Even as the World Economic Forum in 2023 ranked Afghanistan last among 146 countries in a study of gender gaps, a sliver of hope has emerged for Fatima and others desperate to continue their education.

The Afghanistan Law and Political Science Association (ALPA)—led by Bashir Mobasher, the inaugural Afghan Exile Scholar Postdoctoral Fellow in the College of Arts and Sciences’ Department of Sociology—is among several organizations that have launched underground schools and clandestine online education programs for women and girls. In fall 2023, the collective of exiled Afghan scholars, based in Falls Church, Virginia, offered 15 free college-level classes for 400 students in tenth grade through graduate school and beyond as part of its Online Education Academy. This spring, ALPA doubled its courses to 30.

Topics include the hard sciences, gender studies, human rights, advocacy and civic engagement, law, critical thinking, the arts, scholarship preparation, and more. English language courses are particularly popular because so many girls dream of escaping Afghanistan to study abroad, while mental health classes, which explore emotional wellness and anxiety management, seek to combat skyrocketing rates of female depression and suicide. The Guardian, citing leaked data from 11 provinces, reported last year that women now account for the majority of suicides in Afghanistan—a trend not seen elsewhere in the world.

In accessing the online classes, students—who learn about the program through social media and whisper networks of family, friends, and classmates—face myriad challenges, including economic constraints, inadequate electrical infrastructure, and unreliable technology and internet. According to the World Bank, even after nearly two decades of Western-led intervention and engagement with the world, only 18 percent of Afghans have internet access.

Safety is also a paramount concern, which is why all student names are kept secret. “Online learning offers a potential lifeline for many Afghan girls who have no access to education,” Mobasher says. “However, the current political climate in Afghanistan presents significant challenges for online education initiatives. Ensuring the safety, security, and quality of online education resources for Afghan girls remains a critical concern for us.”

The classes are taught by AU faculty, including history professor Max Paul Friedman, sociology professor Alexandra Parrs, associate dean of undergraduate studies Núria Vilanova, and Ernesto Castañeda, director of AU’s Immigration Lab and director of the Center for Latin American and Latino Studies, along with scholars from other universities.

During one of the first ALPA classes in fall 2023, Friedman spoke about critical thinking and its relationship to the development of an independent personality. “I was impressed and moved by the enthusiastic response of the students, whose warmth and engagement came through despite the anonymity required by the format,” he says. “So many of them are determined to pursue their education regardless of the persecution they face, and they have built a sense of community through the class that is often the only source of connection to others outside their homes. These classes are truly a lifeline in a dark time.”

In all, hundreds of thousands of Afghans have fled the county since 2021, seeking asylum around the world. Among them are large numbers of scholars who knew that the Taliban would target academics, people in positions of influence, and families with international connections. An estimated 70 percent of Afghan law and political science professors are living in exile today—including Mobasher, who taught at the American University of Afghanistan (AUAF) until the fall of Kabul in 2021.

Although Mobasher made it to safety in the US, many AUAF faculty, staff, and students weren’t as fortunate. They found themselves trapped in Kabul without visas, unable to leave their country as the Taliban closed in. Knowing that those affiliated with the university would face persecution under the new regime, they made the difficult decision to burn documents and destroy computer servers across campus.

Mobasher lost most of his career’s worth of files and notes—everything that wasn’t backed up on his laptop. When AU hired him in January 2022 with support from the College of Arts and Sciences, Eagle alumni, and the Afghan Challenge Fund of the Open Society Network, he resolved to start anew. But even while teaching classes at AU and writing his first book, Constitutional Law and the Politics of Ethnic Accommodation: Institutional Design in Afghanistan, Mobasher—in his role as president of ALPA—remains keenly focused on the fight for human rights back home.

“It’s my civic duty and my way for fighting the Taliban and the dogma of the Taliban,” he says.

ALPA was founded in Afghanistan in 2019 as a forum for conferences and workshops and to encourage research, publications, and the exchange of ideas. After the Taliban took over, the group’s members reconvened online from across Europe and the US to discuss the best way to redefine their work in exile. Offering an education for girls left behind seemed like a natural fit.

“Initially, I offered a Critical Social Thought class as a pilot program for more than 20 Afghan students during the summer of 2022,” Mobasher says. “That fall, I was joined by Zahra Tawana, a James Madison University graduate student, who taught an English class. Once we concluded that our program was successful, we invited other members of ALPA to get involved and invest in online education for Afghan girls and women as its new mission.”

In Afghanistan, girls and women have been left with two paths, says Mobasher. They can try to leave to study in other countries, which typically requires English language skills, a spot at an American or European university, a generous scholarship, and travel to Pakistan to obtain a visa from an embassy. It’s not easy, but thousands of Afghan women have done it—in fact, many live now in the Washington, DC, area.

The other, perhaps even more difficult path is to stay in Afghanistan and wait things out. “The first time the Taliban collapsed, we rebuilt our country and created a couple of generations of peace and human rights activists,” Mobasher says. “We have so many talented people waiting for whenever the Taliban is gone, ready to pick up the pieces and start to rebuild.”

Layla* is one of those who stayed behind. The 22-year-old was studying politics and law at Kabul University before the Taliban took over. She now takes ALPA classes in secret. “Most [members] of our class are suffering from mental illness because schools are closed, universities are closed,” she writes. “All our hopes in life are gone. Our only hopes are to go to school and for our restrictions to end, so we will be able to live freely.”

Mobasher and his colleagues want to support the dreams of Layla, Fatima, and their Afghan sisters and grow the ALPA’s Online Education Academy into a formal online college with accredited 100- to 400-level courses. To that end, the group is standardizing the curriculum and collaborating with outside educational institutions for partnerships and accreditation.

In the meantime, Mobasher holds out hope for his fellow citizens who remain under Taliban rule. “I dream that they can someday be free, that they will be able to get an education, to work, to live in peace. Afghanistan was a patriarchal society even before the Taliban returned, and it will still be a struggle for women after the Taliban, but at least I hope that girls and women will be able to keep learning and finally be able to contribute to Afghan society again.”

*Names and identifying details have been changed for the safety of students.