Once upon a time, in a faraway land known as 1985, just 18 of 2,500 children’s books—less than 1 percent—featured an African American’s name on the cover.

Over the next 29 years, books by a Black author or illustrator never eclipsed 3.5 percent of annual publications, according to the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC). By 2019, the total stood at 6 percent.

Diversity in children’s books is no longer a unicorn (13 books about which were published in 2019), but it’s still far from the norm.

Based at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, CCBC reports that 83 percent of the 3,717 picture books, early readers, and chapter books (excluding nonfiction) published in 2019 were penned by white authors. And in the words of Mark Twain, they wrote what they know, with 42 percent of books centered on a Caucasian character. More books featured an animal protagonist than Black, Latinx, Jewish, Hindu, and Muslim characters—combined.

“I can name at least three books about narwhals,” quips Annie Lyon, CAS/MA ’03. But biodiversity isn’t the problem, says the head librarian at the Langley School in McLean, Virginia.

“Books help normalize diversity for children and better equip them for life, so when they encounter a situation that’s different from their own—whether it’s a classmate with same-sex parents, a transgender classmate, or a deaf classmate—they’ll be able to navigate that situation with kindness, understanding, and empathy,” says Lyon, who worked at the DC Public Library for seven years before joining the private school in 2020. “Books show kids that outside their little bubble is a wonderful, diverse world.”

And to access that world, we need only crack a window.

In 1990, Ohio State professor Rudine Sims Bishop wrote an essay that continues to serve as a north star for educators, researchers, authors, and librarians. “Books,” she opined, “are sometimes windows, offering views of worlds that may be real or imagined, familiar or strange.”

But in the right light, a window becomes a mirror.

“Literature transforms human experience and reflects it back to us,” Bishop continued, “and in that reflection we can see our own lives and experiences as part of the larger human experience.”

Take poet Jordan Scott’s I Talk Like a River, which gives voice to the 3 million Americans who stutter, including 5 to 10 percent of children. Both a mirror and a window, the 2020 picture book opens with a boy standing before the latter, taking an inventory of everything he sees.

“I wake up each morning with the sounds of words all around me. And I can’t say them all. . . . The P in pine trees grows roots inside my mouth and tangles my tongue. The C is a crow that sticks in the back of my throat. The M in moon dusts my lips with a magic that makes me only mumble.”

The boy learns to accept his stutter—as did Scott—after his father takes him to a river, where they watch the water bubble, churn, whirl, and crash. Just like words. “This is how my mouth moves,” the boy says. “This is how I speak.”

Scott’s story exemplifies the #OwnVoices movement, which promotes books by cultural insiders. The Twitter campaign was launched in 2015 by Corinne Duyvis, whose young adult novel, On the Edge of Gone, is only the third written by an openly autistic author that features a character on the spectrum. The idea, she told Publishers Weekly in 2020, “was to just toss out book recommendations.” Instead, the hashtag became a rallying cry.

As assistant manager of the children’s department at Central Library in San Antonio—the largest majority-Hispanic city in the country—Shannon Seglin, SOC/BA ’00, seeks out stories that reflect her community’s shades of brown. It’s getting easier: Per CCBC, 5.3 percent of books published in 2019 featured a Latinx character and 6.1 percent were bylined by a Latinx author or illustrator. But change isn’t coming as quickly as it should, given that Hispanics, now 60 million strong, are 18 percent of the US population.

A librarian since 2004, Seglin says books like Isabel Quintero’s My Papi Has a Motorcycle, a little girl’s ode to her father and her vibrant immigrant neighborhood, are rooted in the lived experience of the author, which resonates with kids who long to see themselves in the pages of book. But authenticity and cultural awareness are key.

“Mirrors and windows are great—unless they’re reinforcing negative stereotypes or undermining the concept that differences should be [celebrated],” Seglin says.

Case in point: A Fine Dessert, which chronicles four families in four cities over four centuries making the same blackberry fool. Critics dubbed the 2015 picture book, which features an enslaved girl in nineteenth-century Charleston, a “delicious treat,” while others panned the all-white creative team for sugar-coating the brutal realities of America’s original sin. (The publishing industry is overwhelming white, female, and heterosexual, according to a 2019 survey by Lee & Low Books.) Author Emily Jenkins apologized and donated her writing fee to We Need Diverse Books, a seven-year-old nonprofit that curates inclusive reading lists and antiracist resources.

Parents, who spent $2.8 billion on kid lit in 2019, say they too want diverse books. Scholastic reports that 58 percent of them believe cultural heterogeneity is “extremely or very important,” with people of color expressing greater levels of support than their white peers.

But the books they’re buying seem to reflect a nostalgia for their own childhoods.

The Poky Little Puppy, one of the first 12 Little Golden Books released in 1942 is the top-selling US picture book of all time, while the 10 bestsellers of the last 25 years include Green Eggs and Ham, Goodnight Moon, and The Very Hungry Caterpillar—all of which were written before 1963.

Some parents also hold Golden Book–era notions of what diversity actually means. Per the biennial Scholastic survey, less than half of them believe that diversity in children’s books includes the differently-abled (49 percent), people of color (46 percent), and those who identify as LGBTQ (21 percent).

But diversity is not a Choose Your Own Adventure—it’s an anthology. From Indigenous people to immigrants, everyone’s part of the narrative.

Lyon says kids understand that better than most. “They don’t know something is ‘wrong’ until we tell them.” Free from the biases of their parents, youngsters view diversity in the same way the best books present it: as normal, even unremarkable. “Diversity is not something that requires a big, red arrow: ‘Look, Pedro’s in a wheelchair!’ It’s just presented as the way of the world.”

Two years ago, the director of a childcare center asked Seglin to bring by a few books about families. “I pulled some about incarcerated parents, same-sex parents, single-parent families, and divorced parents,” she recalls. “I’m not sure they expected that, but they were so happy that all the kids could see their families in a book.”

No red arrow required.

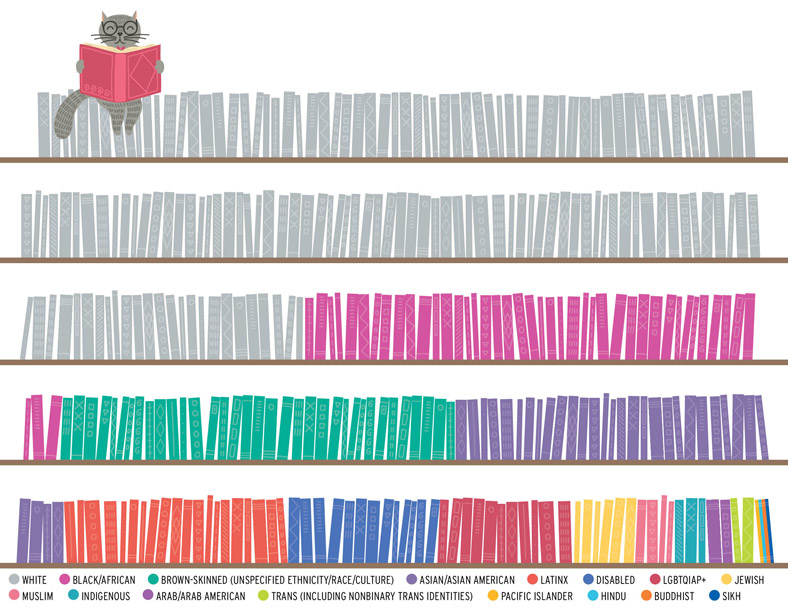

how does diversity stack up among characters in children's books published in 2019?

According to CCBC, the overwhelming majority—41.9 percent—focused on a white character, followed by Black/African (11.9 percent), brown-skinned (9.3 percent), Asian/Asian American (8.7 percent), and Latinx (5.3 percent). A disabled character was featured in just 3.4 percent of books, while 3.1 percent centered on a LGBTQIAP+ character. A Jewish child was featured in 1.6 percent of books, an Indigenous or Muslim character in 1 percent. Arab/Arab American (0.6 percent), trans (0.5 percent), Hindu (0.1 percent), Pacific Islander (0.1 percent), Buddhist (0.03 percent) and Sikh (0.03 percent) round out the least represented populations.

Looking to diversify your child's library? Here are a few of Lyon and Seglin's favorites:

Before the Ever After by Jacqueline Woodson

Radiant Child: The Story of Young Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat by Javaka Steptoe

The Big Umbrella by Amy June Bates

Holi Colors by Rina Singh

Yasmin series by Saadia Faruqi

Papa, Daddy, and Riley by Seamus Kirst

Emma Every Day series by C.L. Reid

In the Year of the Boar and Jackie Robinson by Bette Bao Lord

Thank You, Omu! by Oge Mora

Hank Zipzer series by Henry Winkler

Benji, the Bad Day, and Me by Sally J. Pla

Merci Suárez series by Meg Medina

Alma and How She Got Her Name by Juana Martinez-Neal

It’s OK to be Different by Sharon Purtill

Lovely by Jess Hong

An ABC of Equality by Chana Ginelle Ewing

Darius the Great series by Adib Khorram

When Aidan Became a Brother by Kyle Lukoff

We Are Water Protectors by Carole Lindstrom

Front Desk by Kelly Yang

Uncle Bobby’s Wedding by Sarah S. Brannen

Missing Daddy by Mariame Kaba

The Blue House by Phoebe Wahl

Emily’s Blue Period by Cathleen Daly

Beyond Skin Deep

In 2013, Katrina Parrott’s daughter, Katy, a junior at the University of Texas, was home from college and texting a friend. “It sure would be nice,” she mused to her mom, “to send an emoji that looks like me.” Both mother and daughter are African American.

Parrott’s first thought: What’s an emoji?

Her second: challenge accepted.

Japanese designer Shigetaka Kurita created the emoji, a 12-by-12 pixel “picture character,” in 1997. His original set of 176—now part of the permanent collection at New York’s Museum of Modern Art—included a heart, all phases of the moon, a fax machine, and five facial expressions: happy, mad, sad, scared, and tired.

In 2010, Unicode—the Silicon Valley consortium that includes Apple, Facebook, Google, Netflix, and more—officially adopted the high-tech hieroglyphics and standardized them across all carriers. (Before, someone could send their beloved a heart emoji and it might appear on their sweetie’s cell as a square.) Of the hundreds of proposals Unicode receives, it only encodes about 60 emoji each year. (New for 2020: plunger, accordion, ninja, tamale, and bison—which hopefully speaks more to our resiliency amid COVID-19 than a dodo or woolly mammoth.)

By the time Parrott’s daughter was texting her friend, there were hundreds of emoji to choose from—but the eight faces, while representative of different generations, were all white.

“I thought it was a great opportunity to represent everybody,” says Parrott, Kogod/BSBA ’80, who had just left her job with NASA as a program manager for its logistics contract. “I thought, I’m not just going to do one—I’m going to do five skin tones.”

Parrott copyrighted her iDiversicons in July 2013 and three months later, her collection of 300 multicultural emoji debuted in Apple’s App Store. Soon after, she introduced a color wheel that allows users to customize the complexion of their emoji.

“It felt great to pioneer such an inclusive idea,” says Parrott, who’s featured in the 2019 documentary, The Emoji Story. “It moved me to know that people could finally see a face that looked like theirs.”

According to Wired, 92 percent of people online use emoji. Linguist and Silicon Valley veteran Tyler Schnoebelen, who also appears in The Emoji Story, says it’s important that they all see themselves reflected in the faces of emoji: from a Muslim woman in a hijab to a Black scientist to a Hispanic professor.

“I think it’s exactly because emoji are being used to express people’s feelings and their identities and their relationships that they feel the need to be represented there. Here’s this resource that’s available to us to give out hearts and smiley faces, but then I scroll over a few screens and I see a bunch of people that don’t look like me or don’t represent me or the things I care about . . . and that suddenly starts feeling off and, in some ways, colors the happy, smiley faces and the red hearts,” says Schnoebelen in the film. “This is a platform where people can say, ‘I do or do not belong.’”

Although Parrott pitched Apple in 2014, they declined to partner on her five skin tone emoji and a year later, the tech giant launched a similar concept. In 2020, she filed a copyright infringement lawsuit against Apple in federal court, which is still pending.

Even though her business suffered after Apple unveiled its customizable emoji, Parrott has continued to innovate, more than tripling her offerings to 1,000. Inclusion is still the engine that drives iDiversicons, which in 2015 became the first to add emoji of people with amputated limbs, wheelchairs, and hearing aids to mark the 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act. There are also interracial and same-sex families, and even a Black Santa Claus. And in 2020, Parrott added COVID-inspired emoji that depict hand washing and mask wearing.

Eight years after her daughter planted the seed of an idea, Parrott is fluent in the language of emoji. Her favorite: a Black woman blowing a kiss. “I do a lot of texting,” she says, laughing, “so I blow a lot of kisses to my family and friends.”