Virgin Galactic stood at a critical threshold in early September 2016, facing opportunity and non-atmospheric pressure.

The company was on the precipice of returning the SpaceShipTwo project skyward after two years spent redesigning the vessel. A series of flights would allow engineers and pilots to troubleshoot in real time and prepare the spacecraft—if all went according to plan—to eventually eclipse the Kármán line 60 miles above the Earth’s surface and soar into the heavens.

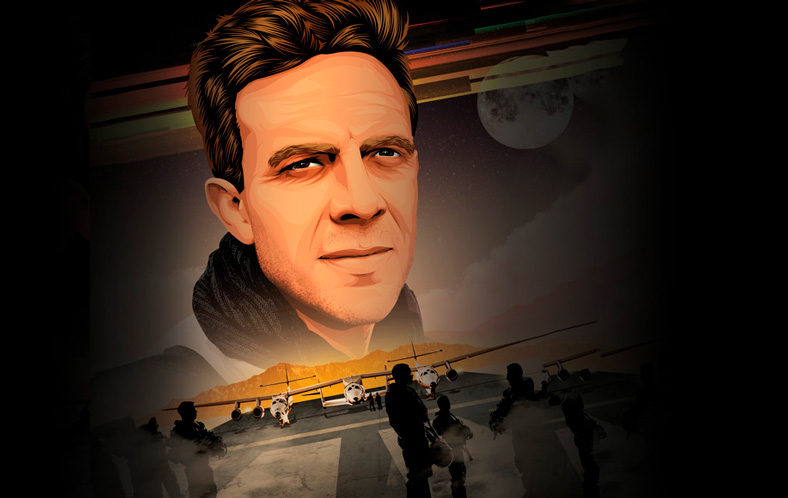

Lead test pilot Mark Stucky was slated on September 8 to conduct a “captive carry,” flying the WhiteKnightTwo cargo aircraft with SpaceShipTwo attached at its belly, like an eagle dangling its rodent lunch. It was an innocuous mission (by test flight standards), and it would go fine, but the anxiety building up to it was palpable. SpaceShipTwo had been grounded since 2014, when pilot Mike Alsbury, Stucky’s best friend, committed a fatal error: deploying the ship’s proprietary feather system early, unleashing a flash flood of drag that ripped the aircraft apart. The mistake killed Alsbury and severely injured fellow pilot Peter Siebold.

Virgin Galactic carried the burden of grief and the knowledge that it couldn’t afford more screwups. That made today’s blunder—late paperwork— particularly maddening. Stucky and Todd Ericson, vice president of safety and test, were livid. They stormed into a small conference room, directing their ire at Doug Shane, president of the Spaceship Company, Virgin Galactic’s manufacturing arm.

“What the hell?” exclaimed Ericson. “To be here, five hours before the first brief, and to be having this discussion? We have failed. This is not the way to run a flight test organization.”

The admission of programmatic shortcoming made the fly on the wall uneasy—but only because the buzz now focused on him. As Nicholas Schmidle, SIS/MA ’05, sat behind Shane recording the exchange with his Livescribe pen, the executive turned and told him that he didn’t want “anyone in this room to feel like this is going to come back to bite us. Are we clear on that?”

Schmidle, halfway into a four-year journey embedded with the company, asked what “clear” meant. Shane replied: “I feel uncomfortable with you sitting in here and I’m trusting that this won’t turn into something we’ll all regret later.” The New Yorker staff writer thanked Shane for his trust and buried his nose in a notebook now dripping with reporting juice, allowing the tension to dissipate enough to avoid a forced exit.

“People are very uncomfortable admitting to it, especially in the presence of reporters,” says Schmidle, “but when you overhear or witness discussions of failure, those are the moments that genuinely feel real.”

Schmidle’s great get provides an emotionally charged midpoint in Test Gods: Virgin Galactic and the Making of a Modern Astronaut, the May 2021 book hailed by the New York Times as a “masterly work.” The tale of Virgin Galactic’s slice of the commercial space race—deeply personal and deeply reported—reminds us that the path to space is not linear but a series of looping contrails. Perfection is near impossible but critical. Risks are real and ever-present. And in a business that burns fuel at 5,800 degrees Fahrenheit, boiling points are inevitable.

Sixteen reporting trips to Virgin Galactic’s desolate Mojave, California, operating base, hundreds of interviews, and a hard drive filled with documents, emails, and cockpit videos revealed an important insight: Stress testing rockets exposes the vulnerability of those who build them, fly them, and—as Schmidle came to learn—write about them.

The company of engineers, pilots, and executives at Sir Richard Branson’s spaceflight firm in a small desert town feels off-limits. But it’s the type of scene Schmidle has spent his career painting for readers.

He found journalism after undergrad, when still-fresh American wars in the Middle East created a need for overseas reporting but not full-time reporters. “I saw freelancers breaking into the business by taking extraordinary risks and wondered if I could do the same,” he writes.

Former AU professor Carole O’Leary nudged him to take one after his first year at the School of International Service, arranging for him to spend the summer studying at the University of Tehran. Schmidle’s Farsi skills faded but the access bug endured. He published a magazine feature, two op-eds, and a travel piece, hooked by the rawness and exclusivity of his reporting.

“It was the first time that I felt I was someplace that I was not supposed to be and was witnessing something unfiltered,” Schmidle says. “It was in some ways proof of concept: ‘OK, I can go places and write about them and I can actually convince someone to pay me to write about what I’ve just seen.’”

The assignments intensified. As he finished grad school, Schmidle earned a two-year fellowship in Pakistan from the Institute of Current World Affairs. He and his wife, Rikki, departed on Valentine’s Day 2006. The fellowship’s only requirements: learn Urdu and write about what you see. He beat Pakistan’s military into the Taliban-controlled Swat Valley, witnessing enough to land a byline in the New York Times Magazine. “Next-Gen Taliban” made international news, in part because Schmidle was expelled from Pakistan shortly after publication. He expanded on his experience in the 2009 book To Live or to Perish Forever.

He’s taken similarly big swings for the New Yorker, writing about war crimes in Kosovo, a Russian arms dealer, the death of Navy SEAL sniper Chris Kyle, and antiquarian book forgery. He was named a National Magazine Award finalist for a 2012 story on the Seal Team Six mission to kill Osama Bin Laden in Pakistan.

Schmidle pitched Virgin Galactic to his editor two weeks after Alsbury’s death. He’d need access to the insular world of commercial spaceflight, so he leaned on test pilot C. J. Sturckow—not a professional contact, but a personal one, having attended family barbecues at USMC Air Station Beaufort in South Carolina when Schmidle was a kid. (Sturckow flew with Schmidle’s father, retired US Marine Corps lieutenant general Robert Schmidle, CAS/MA ’03, on the first night of Operation Desert Storm.)

Sturckow didn’t open the door, but showed Schmidle the knocker, introducing him to then vice president Mark Moses in 2014. Schmidle’s pitch: embedded access akin to Buzz Bissinger’s Friday Night Lights—if Boobie Miles knew how to fly F-15s. Moses “had techs and engineers and pilots with greasy hands and heavy hearts working in the middle of nowhere, trying to do something no one had ever done before,” Schmidle writes. Moses and Branson felt theirs was a story worth documenting, and Schmidle became a spaceport regular.

The challenge, which the writer approached with the artful precision of an F-35 Lightning II pilot: making all readers—aviators and those who just wear them—regulars too. It’s why, for example, Schmidle delves into the technicalities of a SpaceShipTwo horizontal stabilizer malfunction while also describing it in lay terms (“the ship wanted to roll upside down”). He also grounded his reporting by soaring 8,000 feet above it, flying with Stucky in a two-seat aerobatic plane and graying out during a five-g bank so he could describe the sensation to readers.

A few stomach-churning moments broke down barriers with pilots while solidifying Schmidle’s decision to not follow his father into the cockpit. He’s fascinated by the psychology of the elite aviator, but “not all that interested in the elite aviation of it all.”

Despite its shared goal of slipping the surly bonds of Earth, Virgin Galactic takes a different trajectory than its competitors. Blue Origin and SpaceX utilize a vertical takeoff, vertical landing approach that meshes well with automation. Virgin Galactic is an airplane company on steroids, relying on the steadiness, brains, and bravery of pilots to safely reach the promised land.

The heavy lift of human hands in-flight is why Schmidle knew early on that Test Gods would be a story about people, and one person in particular: Stucky, a former marine, TOPGUN graduate, and longtime test pilot who had always dreamed of being an astronaut, thrusting closer with each flight.

“He stared hard at me but looked like a man with secrets in search of someone to share them with,” Schmidle writes of their first meeting over drinks in 2014.

Schmidle learned from cockpit videos that Stucky was the coolest of his peers when ship or self was on the line. He heard the same from Stucky’s colleagues—no small praise in a profession dominated by outsized egos. Schmidle spent time enough with Stucky to watch him cancel family Thanksgiving plans to read old X-15 manuals to prepare for his first suborbital space flight in 2016. Stucky also unpacked a life story that included a close friendship with Alsbury, a divorce, and a fraught relationship with his son.

“His willingness to talk about personal failures as a father, as a husband, as a pilot carried a weight. You know that that’s a burden he has unburdened himself of by sharing. In the process of doing that, there’s a bond and a trust established there, in the professional domain and the personal,” Schmidle says. “I realized that this was more than just a cool story about a spaceship.”

It’s one whose plot extended to the author. Stucky recognized in the reporter’s face a hotshot captain he once knew that “never met a rule he didn’t mind breaking”—Schmidle’s father, Robert. And Schmidle saw in Stucky’s candor a chance to learn more about his dad.

Schmidle would call friends of Stucky (call sign Forger) and inadvertently glean a few additional anecdotes about Rooster, his father—like the time in April 1994 when, flying on low fuel at low elevation, he took out a Serb tank on a bridge in Bosnia.

“He had performed feats that I could not imagine performing,” Schmidle writes. “I wanted to know how he felt and what he was thinking at the time. But my dad was protective of his inner life.”

Test Gods felt like the right time for Schmidle to write about an “extraordinary man who flew fighter jets, and raced motorcycles, and hunted for wild boars with a longbow and home-fletched arrows, and earned a PhD in philosophy, and wrote his thesis on Wittgenstein, and lectured at the Sorbonne, and retired as a three-star general, which he took hard because he wanted four.”

Schmidle reflected on his early rebellion against his dad, who would leave on lengthy deployments and maintain a veneer of emotional distance upon his return. On losing interest in the idea of becoming a fighter pilot, perhaps due to fear of failure along the way. And on how, as he grew older and had sons of his own, he began to perceive some of his father’s flaws as strengths. Schmidle—who conducted a series of interviews with Robert as part of his reporting—thought a lot about the qualitative differences in their lives. At 38, Robert was building toward 4,700 career hours in tactical fighters. At the same age, Schmidle was trying to make sense of those life experiences on paper.

“There was kind of a humble admission as I watched [cockpit] videos or read letters that my dad was sending home when he was my age,” Schmidle says. “There is a massive gulf between those of us who write about these things and those of us who do these things.”

Hunkered down in his home in London early in the pandemic, Schmidle found it therapeutic to commit to words the memories and emotions with which he had long wrestled. It was also difficult for Schmidle to tactfully pair reporting and first-person narrative “and probably just as difficult to share with [Robert].”

But once he did?

“Cathartic, two days later, to hear his warm reception to it.”

Schmidle started writing passages early as an embed. He had worked out a setting, main character, through line, and conflict. He had enough audio to make Ken Burns blush, the spine of what would become a 16,000-word New Yorker piece—“Virgin Galactic’s Rocket Man”—on Stucky and SpaceShipTwo, and later, a book deal. He just needed endings for his two main narratives, and they arrived fortuitously in consecutive flights.

On December 13, 2018, Stucky and Sturckow flew SpaceShipTwo 51 miles skyward, finally taking Virgin Galactic to space and earning Stucky his commercial astronaut wings.

“Wow, that seemed like a long time coming; for some of us, decades,” Stucky said.

The second ending, in February 2019, looped a tidy bow around Schmidle’s storyline. As they prepared for the move across the pond, the author and his family took an RV trip to Mojave, where Schmidle’s sons, Oscar and Bohan, received a tour of the Virgin Galactic hangar from Stucky and later watched another pair of pilots reach space through a pair of binoculars. The Schmidles craned their necks “as gestures of humility,” Schmidle writes, “astonished by the courage required to push the envelope, to go beyond.”

Schmidle felt his reporting was complete, and Virgin Galactic helped solidify that decision, pulling his embedded status after an August 2018 New Yorker article. (Stucky, too, would later pay a price for his comments in Test Gods when he was fired by Virgin Galactic two months after it published.) Moses instructed employees not to speak with Schmidle, though many relationships endured, and the company revoked an invitation from Branson to visit his private island in the Caribbean the following spring.

The move somewhat surprised Schmidle, who knew several senior executives, including Branson, were happy with his presence and willing to continue the relationship. Schmidle knew, too, that he wouldn’t have devoted seven years to writing about Virgin Galactic “if I didn't think that what they were doing was extraordinary and inspiring and incredibly cool.”

Cool is also the allure of space tourism to the super-wealthy. It’s why tickets for Virgin Galactic space flights, on sale as of August, start at $450,000 for a 15-minute trip, and why a Japanese billionaire pre-reserved a 2023 SpaceX flight around the moon three years ago.

Virgin Galactic was the first commercial space company to go public and first to fly its founder to space this summer—nine days ahead of Blue Origin’s Jeff Bezos—despite Branson’s ship flying outside its designated airspace. Whether Virgin Galactic’s approach to space is sustainable long-term is another question.

“There are clearly the personal finances, the customer desire, and increasingly the technological know-how to make [the industry] happen,” Schmidle says. “I just don't know that Virgin Galactic is the company that’s going to be able to deliver on that promise. But if not them, there are other companies that certainly will.”

In rocketeering, as in writing, there is ambition to fill an empty space.

Excerpt from Test Gods: Virgin Galactic and the Making of a Modern Astronaut by Nicholas Schmidle

A split second into the mission Mark Stucky knew something was horribly wrong. Pushing the stick forward, he had expected to enter an aggressive dive, like a kamikaze bomber racing at its target—in this case the bleak California desert. But now the tail of his spaceship was stalled and beginning to drift, contorting his carefully calibrated dive into an unintended back flop.

The computer on board the spaceship was going berserk—alerts beeping, yellow and red lights flashing. Grunting, Stucky pulled on the stick to try to level out. Nothing happened. He was now upside down and floating out of his seat, 40,000 feet in the air. The straps of his harness dug into his shoulders. The ship was falling fast.

Think.

An average human brain weighs about three pounds and contains nearly a hundred billion neurons; an almond-shaped cluster near the brain stem handles our response to fear. Most people panic when they’re afraid. Their palms sweat, their hearts pound, and their minds freeze—at the exact moment acuity is needed most.

Stucky was not most people.

He thumbed the pitch trim switch, hoping the pair of horizontal stabilizers on the tail booms would bite the air. No response. He reached up and switched to the emergency trim system. No response.

Already upside down, now the spaceship was beginning to spin. Stucky counted each rotation as the plunging craft spun past the sun.

One . . . two . . .

Stucky remained almost mysteriously calm. Clinical. He found an odd sort of comfort in such moments. His job was dangerous enough without letting panic get in the way. He was a test pilot, determined to navigate unexplored aerodynamic realms so that his engineering colleagues could define the spaceship’s capabilities and limits; as Arthur C. Clarke said, “The only way of discovering the limits of the possible is to venture a little way past them into the impossible.”

Each test flight offered some new adventure. But “expanding the envelope,” as test pilots described their work, was not adventurism for its own sake. It was a methodical process that drew as much on the discipline and rigor of the scientist as on the artful improvisation of the daredevil.

Fly, test, notate, adjust; fly, test, notate, adjust.

Stucky rummaged through a mental catalog of personal experiences and training manuals and anything he’d ever read or heard from any other pilot in search of something useful, some way to save his ship—and his life.

He deployed the speed brakes. Nothing. Stepped on the opposite rudder pedal. Nothing. The spaceship continued to tumble and corkscrew at an alarming rate, losing 1,000 feet of altitude every two seconds. The sun kept flashing in the cockpit windows.

Three . . . four . . .

“We’re in a left spin,” his copilot, Clint Nichols, announced over the radio, his voice flat as a clerk requesting a cleanup on aisle four.

Stucky had practiced entering and recovering from inverted spins like this plenty of times in other crafts. They were nonetheless unpleasant and dangerous maneuvers. In 1953, Chuck Yeager was flying an X-1—the same type of rocket ship he used to break the sound barrier—when he entered an inverted spin at 80,000 feet and spent nearly a minute “fighting to try to recover the airplane and stay conscious from the high rotational rates.” He eventually regained control, at 25,000 feet. Thirty-two years later, the stunt pilot who filmed Yeager’s scenes in The Right Stuff was doing stunts for the movie Top Gun when he got into an inverted spin, crashed, and died.

Stucky was confused: he couldn’t understand why the tail had stalled. Stumped, he felt sickened that the last option to avoid an almost certain death was going to require him to unbuckle, crawl down, open the hatch, jump out, throw his parachute, and watch as Richard Branson’s multimillion-dollar spaceship smashed into pieces on the desert floor, and, perhaps with it, Branson’s dream of making his space tourism company, Virgin Galactic, a reality.

Stucky was chasing his own dream. He’d spent almost forty years trying to become an astronaut. He’d done stint in the Marines, the Air Force, and NASA, and he now worked for an experimental aviation firm, Scaled Composites, which Branson, a showboating British mogul, had hired to build and test a spaceship for commercial use. It was beyond zany, Branson’s dream of sending passengers into space aboard this handmade craft they called SpaceShipTwo. But the zany ones were often the ones who made history. When Norman Mailer first embarked on his book about the Apollo program, he couldn’t make up his mind whether Apollo was “the noblest expression of the Twentieth Century or the quintessential statement of our fundamental insanity.”

Branson was not the only one with such ambitions. He had rivals, like Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, with his space company Blue Origin, and Tesla founder Elon Musk, with his company SpaceX. They were all building rockets to take people into space, and Branson was clear that he wanted to be “the first of the three entrepreneurs fighting to put people into space to get there.”

Each had distinct visions for the journey. Virgin had pioneered a unique air-launch system—a mothership, WhiteKnightTwo, had been designed to carry SpaceShipTwo to roughly 45,000 feet so the rocket ship would not waste its energy slogging through the dense, lower atmosphere—while others used a more traditional ground-launch system.

Virgin planned to take half a dozen passengers on a “suborbital” flight, cresting about 50 miles above the Earth. By comparison, what is called “low Earth orbit” starts at 100 miles above sea level; the International Space Station orbits an average of 150 miles about that; GPS satellites, which operate in “medium” Earth orbit, are about 13,000 miles away.

Blue Origin shared Virgin’s suborbital altitude goal for its initial crewed flights but was intent on exploring deep space, too. SpaceX was arguably the most ambitious: Musk wanted to colonize Mars, a minimum of thirty-four million miles away.

But perhaps the most striking distinction boiled down to their belief in the human mind. Blue Origin and SpaceX were run by tech wizards, algorithmic geniuses who trusted in mathematical power to eliminate human error, to one day render fallibility obsolete. Virgin was analog, and despite the futurism of SpaceShipTwo’s mission, the vehicle was relatively simple—cables and rods, no autopilot, no automation.

The fate of the ship was in Stucky’s hands.

Nichols was sure they were going to die: that was the hazard of crewed spaceflight. “If you want to build confidence in space, don’t try sending people there,” David Cowan, a venture capitalist who has invested in several commercial satellite companies, said. “Any failure will be a catastrophe.”

The day was shaping up to be just that. Down on the runway, the lime-colored firetrucks were ready to go. Doug Shane, the president of Scaled, issued the words that only company insiders would recognize as code for a looming disaster. When he uttered the phrase “Blue Zebra,” his colleagues knew to plan for the worst.

But Stucky wasn’t ready to give up just yet. As the spaceship spun and fell calamitously toward the Earth, he remembered one last thing he wanted to try: he hoped to God it worked.

Published by Henry Holt and Company, May 4, 2021. All rights reserved.