Since Rachel Louise Snyder skipped home from school in 1977 to find an ambulance parked in front of her family’s Pittsburgh home, the story of her mother’s death at age 35 from breast cancer became the defining story of her life.

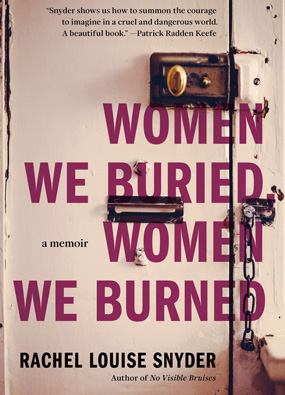

In her masterful new memoir, Women We Buried, Women We Burned, Snyder—who holds a joint appointment in AU’s departments of creative writing and journalism—recounts how the loss of her mother at age eight left her unmoored and untoward. Forced by her grieving father into an evangelical, cult-like existence, Snyder unflinchingly chronicles a volatile childhood that forced her to grow up too fast.

The author of 2019’s award-winning No Visible Bruises: What We Don't Know About Domestic Violence Can Kill Us, Snyder talked with American about resilience, redemption, and finally writing the story that she’s carried inside her for 40 years.

Q. In the book, you describe writing about your mother’s death for the first time as a college sophomore (see excerpt). How did that moment change you?

A. There are writers who return to the same subjects over and over—often a traumatic experience or something else they’re trying to make sense of. That has certainly been true for me. I have returned again and again to writing about my mother, writing about grief, writing about what you are losing when you lose, I think, the most important person in your life at that age.

I had written some poems and things like that, but that moment—it had been about 12 years since her death—was the first time I really tried to capture the loss. I remember that first line as clearly as I remember her: So you want to know what it’s like when your mother dies.

I didn’t realize that writing could be a physical experience. One of the things I teach my students is to listen to their bodies when they’re interviewing somebody or when they themselves are writing something. You sort of feel it in your gut before your mind experiences it or makes you go, “Aha, I’ve written something that feels capital T true.”

For me, that moment sparked a lifelong awareness of the connection between who I am at my deepest self and what I’m trying to achieve through my writing.

My colleague, the late [AU literature professor] Richard McCann—who was so wise and wonderful—used to tell his students to always write from a place of love. As a nonfiction writer and as a journalist, especially, that’s probably not the place you’re going to start. So I tell my students to always write from a place of understanding, by which I mean a place where you are attempting to understand—whether that’s someone else’s story or your own.

I certainly did that with my father. He made what I consider some pretty impactful parenting mistakes. And as a parent myself now, I’m like, wow, how could he have done some of those things? For me to write this memoir, I had to engage in some deep, deep empathetic work to try to figure out where he might have been coming from to make those decisions. He was also in a place of deep, deep grief for many years.

Q. You write about your dad’s complicated presence in your life and loving him despite his mistakes. How did you try to understand his perspective?

A. For many years, I wanted my father to apologize. And even until his dying day, we never agreed on what happened in September of 1985. Did we [Snyder and her three siblings] all get kicked out or did we move out because we were unwilling to follow the rules? I said we got kicked out. He said we were unwilling to follow the rules. Both have their seeds of truth.

But the last Christmas before he died, we both happened to be in Pittsburgh and we went out to breakfast, just the two of us. He said, “You know, looking back, I was much harder on you and David [Snyder’s biological brother] than I was on the other kids because I was afraid of being accused of favoritism.” It was the closest I would ever get to an apology from him. And you know what? I took it. He could not have been, in so many ways, more distant from my life. But he was still my dad, and I loved him madly. It was the best he could do, and I accept that.

Q. When did you realize you had this memoir in you?

A. This was my first novel after graduate school back when I was in my 20s. The first half of it was memoir, the second half was a fictionalization. That book was never published—thank God—but that’s how I got the agent I still have today.

I always knew that I had a unique story, but I wanted to be a writer first before I wrote my own story. I know others have written memoir [as] their first book and it’s super successful, then they get kind of trapped in their own story. So I purposefully waited—but it also took me 30 years to have the distance to be honest about it. Like most people who are young and maybe not removed enough from their own traumas, I could not see anyone’s viewpoint but my own. I also blamed myself entirely. It wasn’t until I was a little bit older that I felt like, wait a minute, this was not all because I was a terrible kid.

Q. Did you have any reservations about how much to share?

A. In writing a memoir, I needed to reveal everything. Well, I probably don’t reveal everything, and I’m not sure I have the self-awareness to even know what I’m not revealing about myself. But I definitely had reservations about the incident in the book with my sister’s boyfriend because I realized that I hadn’t truly grappled with that as much as I should have or as much as any of the victims in No Visible Bruises probably have. I think I’ve been so focused on the loss of my mother that that has taken precedence over everything else. It was hard to know sometimes what to reveal and what might have been an unnecessary exposure.

But in general, the trick of memoir is that you’re not writing autobiography. You’re writing about one piece of your life. What makes it tough is taking the fullness of your own life and figuring out how to cut it up and mold it into something that feels both full and partial at the same time.

I had multiple versions of this memoir. One probably had a hundred more pages about my marriage. But in [the published] version, my marriage takes a back seat.

For me, it takes a lot of trial and error. Like, OK, we’re going to try this. Nope, that didn’t work. We’re going to try this. Nope, that didn’t work either. And it is difficult because this is your life. Obviously, a marriage is significant, but looking at it through the lens of the writer, maybe it’s not important or necessary to the story.

Part of it is learning to trust yourself as a writer. And writing has endless variables. It’s not math where you’re arriving at a predestined answer. You have to be able to look at it with a very calculating, cold eye, and say, this may have affected me emotionally, profoundly, but it’s not going to be in the book. Those are decisions that you make because you have decades of experience under your belt. They’re harder to make when you’re first starting out.

Q. How many years of your life went into writing this book?

A. Fifty-four (laughs). Honestly, I’ve been mulling it off and on for 25 years. No Visible Bruises took me 10 years; when I finished that, I sat down with my publisher and agent and said, “Look, the memoir is going to be my next book. It’s been in the back of my mind and in my heart for many decades.” I had just lost my father, and I had just gone through breast cancer myself—which is another thing that’s left out of the memoir entirely. After that I was like, I really want this one to be next. I felt called to it and I was going to honor that call.

Q. Was writing the book therapeutic?

A. I’ve always resisted the idea of writing as catharsis. If I read one more piece of online advice that tells women to journal, I think my head might explode. And not only have I always resisted that as an exercise for me personally, but I almost feel an anger about it because I think it pathologizes art. And yet, I have to admit with all humility, that there was something cathartic about writing this book, which surprised me. It did feel powerful to say, I had a very, very troubled past—and it wasn’t entirely my fault.

Q. How did losing your mom at such a young age shape your relationship with your own daughter?

A. My parenting style could not be more different than my parents’. Part of that is the age in which my daughter is growing up, but part of that is also that from the moment she was born, we were not playing by the rules that were being dictated to us. She never had a crib, she slept in my bed until she was ready to stop sleeping in my bed. I’ve always felt that what we think of as rules are often just cultural expectations. And because I had her in a different culture [in Cambodia], I was able to situate those in a way that made me say, hold on, I don’t have to ascribe to any of these rules.

And unlike me, she is the easiest-going teenager. She gets straight A’s, but I don’t push her. As long as she has agency and courage and a little sprinkling of humility, I feel like I’ve done the best I can by her.

Excerpt from Women We Buried, Women We Burned by Rachel Louise Snyder

Toward the end of my first year in college, White Lie—a band I booked for several years—and I parted ways. I was growing more consumed with my education, and the guys were starting to think of different paths for their own lives. Frank, the guy who’d gotten me to go to college in the first place, had started dating a woman he would go on to marry, so I didn’t see him much. I was also exhausted all the time, between two part-time jobs and my schoolwork, the world of rock and roll began to seem less and less relevant to where my life was headed.

And writing was taking up more of my free time. My papa Chuck was sending me little encouraging notes (“Not all poetry has to rhyme!”) and authors he thought I should read (Phillip Roth! Ernest Hemingway! Anton Chekhov!). Papa Chuck was a writer himself, a poet and a journalist. Eventually, he was a professor and vice-dean of the Annenberg School at the University of Pennsylvania. Sometimes at school, we held classes outside on the lawn if the weather permitted. My imagined characters were romantic, solitary, and deeply unhappy. I wrote often about a character named Andi who lived in a cabin and spent her days painting. In some ways, I was rewriting those Harlequin romances that I’d snuck off my neighbor’s mother’s shelves so many years earlier. But what I developed was discipline.

I wrote a story in which I created multiple versions of a scenario: driving with two characters as they are breaking up. They’re in a snowstorm in one. In the mountains in another. In city traffic in another, and so on. The descriptions suggested the pain of the breakup. It was the world as we all saw it and also a shadow world operating behind the characters that only the reader saw. Another class exercise: create a scene in which one character knows something the other character does not, and let the reader in on it. Years later, I would find myself using the same technique in nonfiction to show how the signs of intimate partner abuse become visible in victims—in their choices and movements, their speech and silence, their interactions with police, lawyers, judges—once we know (often too late) that they feared for their lives.

Slowly, I began to understand that writing, at least for me, was an empathic exercise in which to examine the complexities and seeming contradictions of people. My fictional creations, but also people like my father, who was authoritarian and loving, inflexible and hilarious. Or my stepmother, who could be every bit as strict as my father, but was also someone you could trust with your secrets. Far from being paradoxical, I eventually understood that we all embody these extremes. I hold in equal measure both cynicism and idealism as an adult now, in much the same way that as a child, I was filled with both violence and grief.

I’d been taking history classes in college every quarter, learning about past and current wars, refugees, political geography. I had always been taught the secular world was something to fear, to turn away from, that it held nothing but emptiness and destruction. But Christians like my parents belonged to that world as much as the rest of us. You could no more absent yourself from history than you could escape your own body. My father may have believed he was separate from those who declared war on non-Christians, or those who drew blood in the name of God, but I was beginning to believe there was a kind of collusion in this willful ignorance. You could admit you lived in these same systems and try to change what was wrong from the inside, or you could stay forever uninformed about them and claim liberation through determined obliviousness.

I took a class my sophomore year in Harlem Renaissance and Black literature. I was introduced to Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, James Baldwin, Claude McKay, James Weldon Johnson, Jean Toomer, Toni Morrison, and others. They wrote of a pain that went so deep it was neurological, generational. One night, lying on my bed, I read a line from James Baldwin. “The most dangerous creation of any society is the man who has nothing to lose.” I felt my brain buzz. I bolted upright in my bed and read it again. Then again and again. The most dangerous creation of any society is the man who has nothing to lose.

I imagine I am far from what Baldwin had in mind when he wrote that line. But sitting up in my bed with The Fire Next Time, it was as if someone had held a mirror to the child I’d been at thirteen, fourteen years old. Grief-stricken and angry. Kicked out of my house, expelled from high school, working one low wage job after another. It was the start of a life without promise or vision. Even if I had, despite these hardships, other kinds of built-in advantages. I wasn’t Black or gay or male or living in a time of pre-Civil Rights America. But I understood the danger of desperate rage. College, unequivocally, had saved me. I remember feeling astonished at the power of Baldwin’s language, enlivened by the raw truth of his words.

By the end of my sophomore year, I was feeling more and more like I belonged in school. My grades were generally As and Bs. I was majoring in English with minors in history and art.

I made some friends on campus. A few guys who all hailed from Alpena, Michigan. The captain of the soccer team and a student so good- looking that the women on campus secretly referred to him as “Jesus.” And his friend, a poet and intellectual who became my best friend for a while. The guys all had nicknames that they’d given one another years earlier—there was Doc and Pine Needle, and the Prophet, and Birdman. They gave me an honorary nickname: Womanchild.

One night toward the end of my sophomore year in college, a single line of exposition came to me: so you want to know what it’s like when your mother dies. I felt the line in my whole body, calling me with an urgency I don’t recall ever having felt. How long had she been gone by then? Ten years? Twelve? I can no longer remember, except to say that I had lived without her already for longer than I’d had the chance to live with her.

I took seriously my papa Chuck’s advice to always carry a pen and paper. And I had taken creative writing nearly every semester since I began at North Central, but it wasn’t until this night, this moment, that writing became a gravitational pull. I sat down at my black Ikea desk, the sides of which were slowly collapsing outward because I’d done something wrong when I put it together. I wrote in colored pen on lined paper.

So you want to know what it’s like when your mother dies? You want to know about the years of desperate pain? You want to know what it’s like to make your father Mother’s Day gifts, to have your classmates laugh at your loss, to have a gravesite to visit on Christmas, rather than a glittering tree?

It was sentimental and maudlin, but it spoke to my deepest loss, the absence that had built a darkness in me over the decades. I’d never articulated this aloud, not in detail, not in a nuanced or even detailed way. Now, I wrote about getting my period. I wrote about being sexually assaulted by a boy named Jackson. I wrote about Judaism. I wrote about kissing and dating. I wrote about Christmases and birthdays missed. I wrote about all the things I imagined I’d know now if she had lived. I felt the piece as I was writing it, a current that ran all the way down to my fingers as I sat gingerly at that black particleboard desk. And as I wrote, I wept.

I had to share it. I had to know if it was as powerful to someone else as it felt to me. And there was only one person I could trust to be honest. I grabbed the paper, ran down the stairs of my apartment, and drove to my best friend Cindy’s house. It was eleven o’clock. Her parents had long since grown accustomed to our late nights, our basement study sessions. To my showing up at odd hours.

I knocked on the back door and when Cindy answered, I motioned for her to come outside, shaking with adrenaline. We sat on the sidewalk next to her house, under a streetlight. Cindy had grown into a beautiful woman. Her sandy blond hair was long, halfway down her back, her brown eyes dark and glinty. She no longer dressed in moccasins and concert T-shirts, but wore long, loose skirts and ironed shirts.

“Tell me what you think,” I said. “But be honest.”

I may have been wearing pajamas. I can only remember the rush to share.

And I read it aloud, there under the streetlamp on that spring night. The memory of this moment is as palpable to me as my mother’s funeral, one of those experiences in which every detail stays. The piece was three pages. A short, sharp, deeply personal essay, told in the second person, but felt in the first.

I didn’t look up until I was finished. Cindy’s held her hand over her mouth. I knew something in me had changed.

Used with the permission of the publisher, Bloomsbury. Copyright 2023.