The Sixth Amendment ensures the right to counsel in criminal cases regardless of a person's ability to pay.

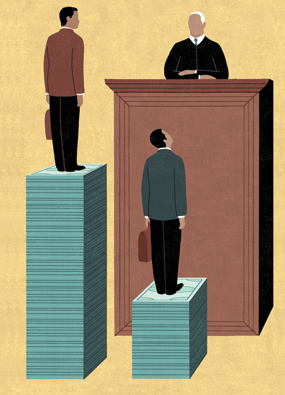

"But what does that mean?" asks Michelle Engert, scholar in residence at the School of Public Affairs (SPA). "Some people will say, 'why should taxpayers provide for a Cadillac level of defense?' Many think defendants simply deserve a Ford. That gets into issues of economic inequality, race, and class in terms of who can afford the Cadillac and whether or not we should all be entitled to the same effective assistance of counsel."

That, and Engert's experience as a state and federal public defender, is the impetus for the SPA class, which explores the unusual roles, responsibilities, and dilemmas faced by attorneys representing the accused. The course begins with a focus on landmark Supreme Court decisions and the development of public defender systems over the last 50 years.

Engert also explores misconceptions about appointed counsel. "People think public defenders aren't good attorneys, that they're inexperienced, or don't care about their clients," she says. "But the reality is, you can have the best, most caring public defender in the world, but if that attorney has 400 other cases, there's only so much time available to give to each client.

"The criminal justice system should deliver just results to everyone equally, regardless of their ability to pay—and it doesn't."