My son Owen is lanky, with a shock of sandy blond hair and big blue eyes that sparkle when he giggles or talks about firetrucks—both of which he does a lot. He eats like a bird, but devours books. At 18 months old, Owen knew more than 100 words (among them: cactus and coffee) and by two, he was speaking in full, descriptive sentences. "The pile driver digs the foundation," he said one afternoon as we walked past a construction site. I had to Google it—he was right.

Owen's immensely curious and affectionate, constantly peppering me with questions and showering me with kisses. "Mommy, who built me? What am I made of?" "Mommy, I love you. You're my girl."

My only child—born four years ago on my birthday—is imaginative, witty, smart, and spirited.

He also has autism.

Didn't see that coming? Neither did I.

Although his vocabulary was exploding in 2014, Owen was doing more screaming than talking at daycare. Clueless, my husband Sam and I chalked it up to the terrible twos. "Kids act out at this age," I said to the teacher. It was as much a question as a statement.

As he got older, the screaming got shriller and more frequent. Even the most benign question—Do you want milk?—was met with shrieks so piercing that they made other kids cry. On our walks home from school, I gently reminded Owen that his outbursts upset people. Logically, he understood this. "Ms. Nancy is a nice lady," he would say of his teacher. "I don't want her to be sad." But in those moments of frustration, logic was overridden by an explosive irrationality that made me want to scream.

Most days Owen refused to participate in circle time and had neither a want nor a willingness to interact with other children. At drop-off the kids swarmed us and squealed hellos to "Owie." We had to instruct Owen, our little wordsmith, to say "good morning" in return—a greeting he mumbled while clutching our legs and staring at the floor.

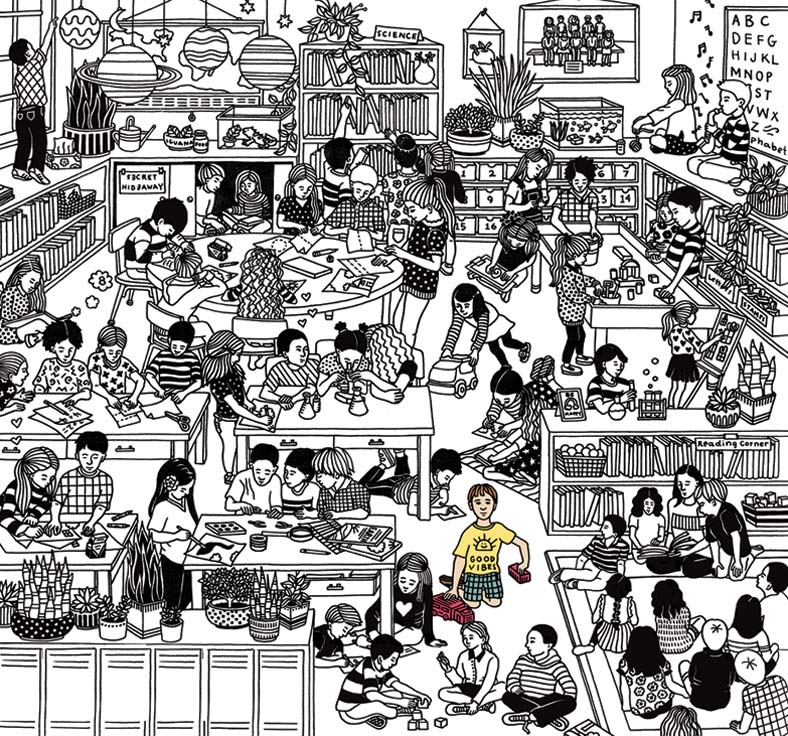

In working on this story, I found a photo his teacher sent us in August 2015. A group of 10 kids is seated on the carpet, holding cardboard tubes up to their mouths—a symphony of homemade horns. Owen, meanwhile, is standing along the back wall, holding the tube by his side and looking off in the distance, emotionless.

How could you not know? I ask myself now.

What's obvious now wasn't then. We assumed that, like me, Owen was simply an introvert who took a while to warm up to others. He's more of a one-on-one kid, we told ourselves. He prefers the company of adults. But as the screaming worsened and the teachers' complaints became more urgent, so did the feeling in my gut that something was wrong.

In summer 2015 I called Owen's doctor, who referred us to a developmental pediatrician with more than 40 years of experience. "Don't be alarmed," she said, "but he might throw out the 'a-word.'"

It was clear that something was going on. But autism? No.

Owen wasn't just verbal, he was a gifted communicator—a "little professor," as one of his teachers called him. I always knew that boys were more likely than girls to be diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)—4.5 times more likely, in fact—and remember feeling relieved when Owen started talking, as I thought that alone meant we'd skirted the "a-word." He looked us in the eye when he spoke and was incredibly affectionate. He could even crack a joke.

I was all for figuring out what was going on with Owen. It's simply that what I knew about autism—or thought I knew about autism—seemed incongruent with his strengths and challenges. I had known people with severe autism and Asperger syndrome. My son bore little resemblance to them.

I was nervous for our 90-minute evaluation with the developmental pediatrician, but his warm, grandfatherly demeanor put me at ease, as did his first question: what do you love most about your son? While we talked, the doctor kept one eye on Owen, quietly observing how he played with a variety of toys and how he interacted with me.

"Does he do that often?" he inquired when Owen asked me—three or four times, rapid fire—to identify a firetruck on the rug. I admitted that yes, he did. "He's clearly a bright young boy. He knows that's a firetruck, but he's caught in a loop." (This is called perseverating, and despite hundreds of hours of therapy, it's something Owen still does. The only way to stop the loop is to misidentify the object—call a firetruck a police car—or to say, "I don't know Owen, why don't you tell me?")

The doctor also expressed concerns about Owen's strong-willed behaviors, difficulty with transitions, social anxiety, emotional outbursts, and inability to interact with peers. "These are some indicators that might suggest mild ASD," he said. An official diagnosis would follow a battery of observations, appointments, and questionnaires. But the message was clear: brace yourself.

In the parking lot 10 minutes later, I strapped Owen in the car, closed the door, and cried.

Autism is a group of complex bio-neurological disorders characterized by difficulties in social interaction, verbal and nonverbal communication, and repetitive behaviors. Previously, autism disorders including Asperger's were distinct diagnoses; in May 2013, they all merged under the vast umbrella of ASD.

ASD is the fastest growing developmental disorder in the United States, affecting more than 3 million Americans and 73.5 million people worldwide. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 1 in 68 children is on the spectrum, up from 1 in 88 in 2008 and 1 in 150 in 2002.

When it comes to their symptoms, no two people are alike. Up to 25 percent are nonverbal; some rock, flap, or spin; others can't make eye contact or respond to their names; and half engage in aggressive behaviors. Many boast unusual interests—in escalators or ceiling fans, for example—and have difficulty sleeping and eating. Although 40 percent of those with ASD have average to above-average intelligence and some are gifted mathematicians or musicians, Dustin Hoffman's autistic savant in the 1988 movie Rain Man is the exception, not the rule.

"The neural story for autism is extraordinarily complex," says psychology professor Catherine Stoodley, principal investigator for AU's Developmental Neuroscience Lab. "More differences exist between autistic brains than between [neurotypical] ones." However, the cerebellum—located at the base of the brain and home to half of its neurons—shows remarkably consistent signs of abnormality among those on the spectrum.

The cerebellum plays an important role in motor control, movement-related functions, and cognitive functions, including social cognition and language—which is the focus of Stoodley's research, funded by a three-year grant from the National Institutes of Health.

"The goal is to better understand how the [autistic] brain is working so we can capitalize on strengths and improve the parts that aren't functioning as well," Stoodley says. But "there are no easy answers, no quick answers," given autism's broad spectrum. "If you look at the population we're studying, IQs might range from 120 down to 70 or lower. Behaviors are so different and so complex, they can be difficult to unravel."

Debate over autism's growing prevalence is akin to the chicken-and-egg argument. Many believe that a broader definition of ASD and more finely-tuned diagnostic efforts have helped to identify more people on the spectrum. However, as the CDC states on its website, "a true increase in the number of people with ASD cannot be ruled out."

There is no cure and no known cause, although DNA plays a big role. Nongenetic or environmental factors that influence early brain development don't cause ASD by themselves, but they can increase a child's risk of autism. Advanced parental age is a risk factor, as are prematurity and low birth weight.

Kids are often diagnosed with autism at three or four years old, which is around the same time they receive immunizations. But correlation is not causation. "At Autism Speaks, we still receive questions regarding vaccines, but as an organization dedicated first and foremost to science and research, we go off of the research, which clearly shows vaccines don't cause autism," says Marley Rave, SPA/MPA '13, national director of major giving at the nonprofit's DC office. The CDC and World Health Organization have also dismissed any causal relationship between immunizations and ASD.

Wandering is a major safety concern within the ASD community. According to Rave, 50 percent of kids with ASD (my son included) wander, bolt, or elope—a rate nearly four times that of neurotypical youngsters. More than one-third of children with ASD are never or rarely able to communicate their name, address, or phone number, according to the National Autism Association. Many are fearful of police and emergency workers, who often lack the training to effectively identify and communicate with people on the spectrum.

We saw this play out (literally, on cell phone video) in North Miami, Florida, in July, when police shot a behavioral therapist who was trying to calm his 27-year-old autistic client. The young man had wandered from his assisted living facility and was sitting in the middle of the street, clutching a toy truck, and screaming at his therapist to "shut up," which officers took as a threat. Police later admitted they made a mistake by shooting the therapist—they were aiming for the autistic man.

"If your child was just diagnosed, you might need some time to get used to the idea. Take a few days. Cry, moan, scream, bitch, blame your spouse's family—do whatever you need to for a little while. A very little while. Then roll up your sleeves and get to work."

When I got to this line in Lynn Kern Koegel and Claire LaZebnik's Overcoming Autism, I laughed out loud. Just a few nights before, Sam and I had angrily shaken the branches of one another's family trees. It was a relief to know the need to point fingers is completely normal.

Autism had inserted itself into our lives overnight. It was surreal, discombobulating, and exhausting. It was all we could talk about, all I could think about. On particularly bad days, I would slip into the bathroom at work for a quick cry. I have always looked at my child and thought: He will be successful, he will love and be loved, he will be happy. Those three letters—A-S-D—rocked my foundation.

Fall 2015 was a whirlwind of appointments. In addition to seeing doctors through our insurance provider, Owen was evaluated by Child Find and referred to Developmental Education Services for Children (DESC) in Montgomery County, Maryland, where we live. The process was incredibly illuminating. We learned that Owen has sensory processing issues (he gets overwhelmed and anxious in a loud restaurant or in a chaotic classroom) and poor gross and fine motor skills, which is common among kids with ASD. We also discovered that Owen's severe gastrointestinal problems, which began plaguing him at three months old, were probably the earliest sign of autism.

The DESC evaluation gave us our first real glimpse of Owen's days at school. "Owen sometimes stopped playing and looked lost in thought as he played with the fringe on his blanket," the psychologist wrote.

My heart ached. But when the official diagnosis of ASD came on October 22, 2015, there were no tears—there was only relief and an overwhelming sense of determination to do everything in my power to help my son. "This is the low point," the doctor told Sam and me. "It will only get better from here."

When Tracey Staley, Kogod/BSBA '84, learned of her son Jeff's diagnosis in 2000, her first thought was: what's Asperger's?

Staley was working at a tech company at the time of six-year-old Jeff's diagnosis and began reading up on Asperger's, a high-functioning form of autism first identified by Austrian pediatrician Hans Asperger in 1944. "I realized, 'Hey, I know a lot of people like this,'" she says. "There was a sense of relief that we finally knew what was going on."

A gifted little boy who loved trains, Jeff developed normally, but Staley and her husband Mike noticed that he would get overwhelmed by loud noises. Once in first grade, Jeff disappeared from the cafeteria; panicked teachers later found him in the classroom, enjoying his lunch in blissful silence.

Jeff's tendency to be literal attracted bullies who teased him about "ants in the pants" or, worse yet, "liar, liar, pants on fire." (According to the National Autism Association, 65 percent of autistic kids are bullied by their peers.) Eventually, things began to even out when Jeff, who was also diagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD), enrolled in a program for Asperger's students in third grade.

Good teachers and a principal who "got it" made all the difference, as did the right psychologist and cocktail of medications. "I'm now confident that he will have a successful life," says Staley, who sits on the boards of the Autism Society of America and the Autism Society of Pittsburgh, where she and Mike live. "But I don't know that I could've said that a few years ago."

Although the Staleys always knew their son was smart, they weren't sure if college was in the cards. Of those with a disability, people on the spectrum are the least likely to attend college, according to a study published in the June 2012 issue of Pediatrics journal. Only one-third go to college, with the majority of them (81 percent) matriculating to a four-year institution from community college.

Jeff defied the statistics. The 23-year-old is now an information technology major at Marshall University's College Program for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder, which offers support around academics, social skills, and independent living. If students miss class, their grad student mentors come knocking; if they ask too many questions in class, they might be given a per-lecture-limit. Marshall's program, established just 14 years ago, is the oldest of its kind on a US college campus.

Now a junior at the Huntington, West Virginia, university, Jeff is thriving. Even his struggles are victories of a sort. "He discovered a social life," laughs Staley. "That got the best of him for a while." Still Staley, who works in human resources, worries about the budding video game designer. Can he sell himself in an interview? Can he stay focused when work, inevitably, becomes a grind? "In life—and at work, especially—you don't always get to do things that you love."

Despite Staley's worries, she's learned never to underestimate her son.

Last year, the Autism Society invited Jeff to speak at its annual conference in New Orleans, alongside NeuroTribes author Steve Silberman. "He spoke in front of 150 or 200 people; I never thought he'd be able to do that," Staley says. "It was a reminder that you always have to look for opportunities for your child to shine."

The doctor was half right when he told us things would get better. They would, but not immediately.

An official diagnosis of ASD meant we could begin pursuing Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) therapy. We also had an Individualized Education Program (IEP) in place with Montgomery County that entitled Owen to weekly sessions with occupational and physical therapists and a special educator.

The only problem: None of the services would kick in until January 2016 and Owen's daycare situation was growing more volatile by the day.

He screamed in the morning when he realized it was a school day. He screamed when I dropped him off. He screamed at daycare—so much so that I was certain we were going to be asked to leave. I started using the back door so I could stay out of the director's line of sight. She had already told us that four parents had complained about Owen's outbursts; that made me feel even more alienated from the other moms and dads, who looked at us with a mix of disgust and pity.

When I picked him up, I would get a full report of Owen's misdeeds from both the teachers and the kids, which was particularly brutal. ("Owie made me cry today.") As an editor, I always begin my critique of a writer's work by pointing out something positive; I was desperate for someone at Owen's school to do the same. Yes, I need to hear about the outbursts. But can you also tell me about that awesome Lego tower he erected? Or how he puffed with pride when you asked him to be line leader?

The last three months of 2015 were among the hardest of my life. All three of us were stressed; our unhappiness was palpable. A doctor once told Sam and me that it's not Owen who is challenging. Rather, we are challenged as parents to adapt, to accept our son for everything he is and everything he might never be. At the time, though, I felt challenged just to get through the day.

According to Los Angeles-based clinical psychologist Darren Sush, CAS/BA '01, CAS/MA '03, parenting a special needs child exacerbates everyday stresses. "Being a parent in and of itself is difficult. But the instruction manual for parents of kids with autism is completely different. Unfortunately, those challenges are often pushed to the side because there's no time, there's no money, there's a guilt that comes with taking a moment for yourself."

A 2014 study by researchers at the University of Illinois found that 32 percent of mothers of children on the spectrum experienced moderate to severe levels of depression, compared to 18 percent of women with neurotypical youngsters. The trend holds true for fathers of kids with ASD, as well.

"If parents are feeling a bit depressed, they're less likely to participate in their kids' lives, and that impacts the children's progress," says Sush, who went into private practice in 2013, working exclusively with parents of autistic children. "It's like getting oxygen on the airplane: you have to put your mask on first before you can help your kid. If you pass out, you're no good to your child."

Resentful, lost, lonely, sad. That's how Owen's diagnosis made me feel. It wasn't until I met Kelly Israel, WCL/JD '15, that I got some idea of what Owen might be experiencing.

Israel, 27, was diagnosed with Asperger's when she was about Owen's age. A whip-smart little girl who lost herself in books, it was Israel's "tempestuous emotions" that set her apart from the other children in her kindergarten class. Social anxiety led to tears, which led to outbursts that didn't taper off until she was in her mid-20s.

"When you have trouble controlling your emotions, it's a constant battle against exhaustion," Israel tells me over lunch near the Autistic Self Advocacy Network (ASAN) in downtown DC, where she works as a policy analyst. "Low-level anxiety follows me wherever I go."

I understand that awful feeling more than Israel knows. I wrestled with postpartum anxiety and debilitating panic attacks after Owen was born. For months, I could feel the anxiety coursing through my body. It was just as Israel describes: constantly teetering between willing the anxiety away and spiraling, helplessly, toward it.

The difference is, my struggles were fleeting. "I've had to practice that control every day for 27 years," Israel says.

I glance around the busy restaurant and ask Israel if anything about the present environment is making her anxious.

"I can hear half of every conversation, I hear music. I have tactile sensitivity so these clothes are uncomfortable," she says, tugging at her black blazer. "And the tails from the lights are distracting."

It wasn't until she enrolled at the Washington College of Law that Israel says she "learned to gain rigid control over my emotions. Lawyers have to be unflappable—that training helped a lot." Law school, which marked the first academic challenge of her life, also forced Israel to confront her difficulty with interpersonal communication.

"I can write any legal brief, no problem. But I wasn't sure about the heavy social aspects of law school. I built up such fear about working with people directly, but I had to overcome it in order to be an effective advocate," says Israel, who participated in WCL's Disability Rights Law Clinic.

In ASAN, a nonprofit created in 2006 by and for people on the spectrum, Israel has found a supportive group of (more) like-minded colleagues—and a mission. "We seek to make the voice of autistic people heard in the halls of power . . . and to create a world where there's more than one kind of 'normal.'"

I ask Israel about her proudest accomplishment.

"My life," she says. "People with disabilities are born into a world where the deck is stacked against them. We are discriminated against and marginalized from social and public life. Being a bar-certified attorney, working for an advocacy organization with a mission I care about, having wonderful friends and loving family, living well and on my own—I'm very proud of that."

Owen began ABA therapy in January 2016. The first morning that we arrived at school to see a therapist waiting for us, I knew ABA was the best thing we could have done for him (and for ourselves). For six months, it had felt like we were throwing our son into the deep end of a pool. Now, he had an advocate, a guide by his side for 25 hours a week.

The first successful use of ABA methods for children with autism was in 1967; today, it's the most recommended, scientifically-proven treatment for kids on the spectrum. ABA is an intensive, structured, and data-driven program. Therapists help children practice a skill, then reward correct responses and positive behavior and redirect or ignore undesirable behavior. For example, now that Owen has learned to refuse politely, he is praised—and his request honored—when he says "no thank you" but ignored when he screams "no!"

Once a month I meet with Owen's clinical coordinator, who goes through charts and graphs documenting his progress around everything from sharing and following instructions to hand washing, classroom participation, and temper tantrums. A spike in the chart indicates a bad day—but spikes are fewer and farther between these days.

I used to fret that Owen's behavior would inhibit his ability to learn; those worries aren't completely assuaged, but they are lessened. Through ABA, Owen has learned to ask for space instead of screaming or hitting (although hitting remains a concern); he's starting to hold short conversations about topics other than firetrucks; he's not only joining circle time, he's participating; and he's practicing calming strategies when he gets upset. The yellow blanket that he used to drag around like Linus from Peanuts is now gone.

I'm in awe of his therapists: two wonderful, 20-something young women who don't yet have kids themselves, but know how to reach my child in ways that Sam and I never could. They are warm, kind, and infinitely patient—but I know it's Owen who's doing the heavy lifting. He will never be completely at ease in social situations, but he's learning how to navigate them. I never forget all the hard work behind every data point on his charts.

ABA is incredibly effective but it can also be expensive. Even if it's covered by private health insurance, which isn't a given (coverage depends on the laws of the state in which the policy is written; Maryland requires ABA benefits, for example, while DC does not), families still have to contend with expensive copays or coinsurance and deductibles. Daily copays can add up to $700 a month.

According to Marley Rave of Autism Speaks, the disorder costs families $60,000 per year in medical care, special education, lost parental productivity, and more. (Last year, costs topped $268 billion in the United States alone.) However, a 2012 study by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania found that the cost of intensive early intervention like ABA "more than pays for itself in terms of reduced needs for therapy and educational support by the time a child reaches high school."

Says Rave: "I've had the opportunity in this job to meet so many different families and parents who are doing the best they can, but they deserve to have an easier road. It's our responsibility to help parents give their kids the best quality of life possible, without bankrupting them."

It's early August and I'm at a café in Tenleytown, waiting on Sean (not his real name), an AU student who's agreed to talk to me about his ASD diagnosis. I have no idea what to expect—how much he'll want to share, or how much he'll trust a person he just met with his story.

Sean describes years of psychologists layering one diagnosis on top of another, until they settled on a combination that best describes his nuanced symptoms: ADD, Asperger's, and executive function disorder, which hinders his ability to manage time, switch focus, and organize. In high school, he also wrestled with depression and suicidal thoughts.

When he enrolled at AU, Sean, disclosed his diagnoses to the Academic Support and Access Center, entitling him to legally-mandated accommodations, including extra time for exams, which he can take in a separate room. Still, challenges remain. Weekly reading and reflection exercises that might take the average student 2 hours take him 10 to 20. He has lots of thoughts—brilliant ones, in fact—but getting them on paper can be excruciatingly difficult.

He works best from the quiet comfort of home—an apartment near AU—so he misses out on the socializing that often happens in study groups. "I think people respect what I have to say and I often stimulate conversations in the classroom, but [students] see me as nothing more than a walking book."

Sean's ASD diagnosis reveals itself mostly in his social struggles. He's resigned himself to the fact that he may never marry and says his diagnosis functions as a shield of sorts. He relates better to older people and says his social life in DC is "nonexistent." He tells me all of this matter-of-factly. It's not meant to elicit pity.

In the 90 minutes we spend together, I'm struck not so much by Sean's social awkwardness, as the conversation flows easily, but by his thoughtfulness and intellectual curiosity. He tells me that, through academics, he hopes to find his place in a society in which he's not entirely comfortable.

"Living in a world that is mostly made of people without ASD is challenging," he says. "Humans are social animals, which makes me wonder if I am incomplete or less human than others."

You know that's not true, I tell him.

"Yes, I suppose that's only one aspect to our humanity."

As Sean and I walk out of the café, I shake his hand and tell him how much I enjoyed our conversation. I see a bit of my son in him—but more than that, I see a smart, interesting young man worth knowing.

"Call me if you ever need anything," I say.

A single word in Australian sociologist Judy Singer's 1988 thesis—neurodiversity—would eventually spark a dramatic paradigm shift. Instead of seeing autism, dyslexia, dyspraxia, and other developmental disorders as diseases, Singer said we should view them simply as variations in human wiring. It was a revolutionary idea, put forth by the mother of a child with Asperger's, who's on the spectrum herself.

"I was interested in the liberatory, activist aspects of it—to do for neurologically different people what feminism and gay rights had done for their constituencies," Singer told journalist Andrew Solomon in a 2008 New York magazine article. Much like neologisms such as biodiversity or cultural diversity, neurodiversity highlights the ways in which society is made richer by people who think, learn, and communicate differently—all while demanding supports to help those people succeed in school, at work, and in life.

Admittedly, it can be difficult to wrap your brain around the idea of neurodiversity (no pun intended). If you're a parent, your view likely depends on where your child falls on the spectrum. As Thinking in Pictures author Temple Grandin said in Solomon's New York piece: "Autism is a continuum from genius to extremely handicapped. If you got rid of all the autism genetics, you'd get rid of scientists, musicians, mathematicians . . . The problem is, you talk to parents with a low-functioning kid, who've got a teenager who still goes to the bathroom in his pants and who's biting himself all the time. . . His life is miserable. It would be nice if you could prevent the most severe forms of nonverbal autism."

I don't believe that Owen's high-functioning autism is something to be cured. My son is not deficient, he is different. Even before his diagnosis, we noticed that Owen assembles his wooden train track in a long, winding line. Most everyone else would put it in a circle or oval, to ensure the track connects. Is Owen wrong? No. And it makes me wonder: what else will he see differently? And might that someday benefit society? Or advance science? Who knows what the unique wiring in autism might inspire.

While I celebrate my son's beautiful mind, however, I don't celebrate the flip side of his diagnosis: the challenges that make his life, and the lives of millions of others on the spectrum, more difficult.

I know some parents will never hear the words "I love you" pass their children's lips. Others—40 percent, according to the National Autism Association—don't get a full night's sleep because they fear their children will wander from the house. Those on the spectrum are chronically unemployed and underemployed. Bullying, depression, and seclusion are also huge concerns. Some autistic kids self-harm or lash out violently at their siblings; others suffer from comorbid conditions like epilepsy or persistent viral infections; and some will never live independently. Many parents fear what will become of their autistic adult children when they die: Who will care for them? Who will love them?

I am keenly aware that many children and adults with ASD are profoundly impaired and that Owen is among the luckiest of the unlucky. In many ways, we don't fit in with children with severe autism and their families whose experiences—while technically under the shared umbrella of ASD—are vastly different from ours. And neither do we fit in among Owen's neurotypical peers and their families.

My son isn't the face of autism, but he is a face of autism. And as my new friend Sean so eloquently says: "just because it's easier doesn't mean it's easy."

In 1993, autism rights advocate Jim Sinclair penned an open letter to parents of autistic children titled "Don't Mourn for Us." He writes: "You didn't lose a child to autism. You lost a child because the child you waited for never came into existence . . . Grieve if you must, for your own lost dreams. But don't mourn for us. We are alive. We are real. And we're here waiting for you."

I've accepted that we may never have a picture of our son with Santa Claus. I've discovered that hand dryers and metal detectors can be terrifying, and that wiggle pads, fidgets, and timers are lifesavers. I know that shirts must be adorned with a firetruck and that grilled cheese is on the menu six nights out of seven. I've embraced the fleet of Matchbox cars that meticulously lines our windowsill. I know that when my son asks to be picked up and whispers "I'm done," his social anxiety is kicking in. And I realize that he hits me more than anyone else because he trusts me more than anyone else.

Over the course of the last year I've practiced patience and empathy like never before, and I've learned to forgive myself when I fail. I've learned that it takes a village, and I'm humbled by and grateful for ours. Most important, I've learned that life doesn't always turn out like you think it will. Owen might not have been the child I expected, but I thank my lucky stars that he's the one I got.

Last year we spent the holidays in my native Arizona. We were driving at dusk along a stretch of Interstate 10 that cuts through a swath of the Sonoran Desert, which was aglow in regal purples, golden yellows, and fiery reds. It was a sunset worthy of a postcard.

Suddenly, a little voice chirped from the backseat: "Mama, who paints the mountains?"

I don't love my beautiful boy in spite of his autism—I love him more because of it.