Science

Full STEAM Ahead

Facing tech worker shortages in some sectors of the economy, there’s a broad consensus to support the STEM fields. There’s also a movement to link arts to science, technology, engineering, and math education, but others fear art will dilute STEM. Thus, we have a national STEM vs. STEAM debate that’s far from settled.

Aside from a longer acronym—does STEAM sound better than STEM? Discuss!—some academics stress the intellectual and practical benefits of including the arts. At American University, signs point toward STEAM, and there are concrete examples of science professors incorporating art into their curricula and work spaces. In the new Don Myers Technology and Innovation Building, the Design and Build Lab (known as the makerspace), the Game Lab, and the Incubator all encourage ingenuity, interdisciplinary collaboration, and a little imagination.

“We really want those to be used university wide,” says Kathryn Walters-Conte, director of professional sciences masters in biotechnology who’s worked with the Incubator and makerspace. “Having the A in there is not only for arts, but also for accessibility. This is not just something exclusively for students who are studying science. These spaces and these resources are for everybody.”

Intersections and Overlap

To help christen the new Don Myers building, Walters-Conte organized AU’s first STEAM Faire last fall. Scheduled around All-American Weekend, the high-turnout event included contributions from biology, chemistry, physics, computer science, and—notably—the dance and audio technology departments.

“It shows how the work they do is also very technical and very mathematical,” she says.

Walters-Conte notes that some AU premed students take dance classes, and there’s student overlap in the physics and audio technology programs. That interplay, she says, is part of a solid liberal arts education.

“It’s not saying, ‘I’m an art person versus I’m a science person.’ I mean, all of us are kind of hybrids. And I think American University actually attracts a lot of people who have a lot of both scientific talent and artistic talent.”

Students can hone their creative and technological acumen through a variety of university programs. For instance, audio technology alum Matt Fagan also used game design classes and the Incubator to develop LightSignature, a piano playing app.

And Walters-Conte says CAS professors are passionate about showing these intersections. “Scientists have this reputation for being very rigid, and we kind of want to show that, ‘Actually, we’re pretty cool and creative as well.’”

The Aesthetic Component

In the Physics Department, Jonathan Newport is one of those creative scientists. Inside his office you can find complex gadgets, which he’s personally designed to enhance scientific understanding. Newport also believes in artistic presentation, and he’s devised visually appealing devices that produce unique sounds.

Among the demonstrations Newport has constructed is one that allows people to 'hear' electronic noise. The device picks up signals from nearby electronic devices, such as cell phones, then amplifies the signals so they can be heard. "Electronic noise is everywhere. For example, our power grid oscillates at 60Hz. If you touch the input to an amplified speaker your body acts as an antenna and you can hear this 60Hz ‘hum’ through the audio system.”

Newport was heavily influenced by San Francisco’s Exploratorium, a museum founded by physicist Frank Oppenheimer (brother of atomic bomb pioneer Robert). “Frank Oppenheimer took a different tack than most scientists, as he was brought up in a family that appreciated the arts,” Newport explains. “The Exploratorium illustrates all the same sorts of physical phenomena that most science museums demonstrate, but they are presented in aesthetically pleasing and creative ways. This approach influences my curricular design and serves as inspiration for the demonstrations I construct.”

Newport strongly supports adding art to STEM. “Is engineering anything without an aesthetic component? You could have something that is very practical, but maybe no one would use because it doesn’t have a good user interface, or it wasn’t interesting to humans,” he says. Newport opines that, “Two of the most interesting features of humans are our ability to understand the universe and our capacity for creativity, and these features are embodied in science and art.”

CAS professors think design projects will make science classes more attractive to non-science majors. When student enrollment in Physics 100 started dropping, Newport revised the curriculum and included puzzle solving, measurement tool creation, and pneumatic rocket testing. “Students have approached me and said, ‘This is the reason I took this class, because I heard we get to build rockets.’”

Exploring the Makerspace

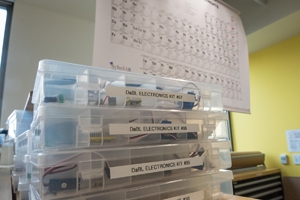

Advances in modern technology sometimes obviate the need for humans. Decades ago, a lot more people could probably build a table or install a light fixture. The Design and Build Lab, also known as DaBL, or colloquially just “the makerspace,” is part of a nationwide movement to get people working with their hands again. That’s why you can find a sewing machine there—a fixture from early 20th century American households. DaBL manager Kristof Aldenderfer describes a place where you not only design things, but get involved in the entire development process.

“We’re finding students who are excited about working for the space. We’re training them on the equipment so they can assist users with their projects, and we’re building out the educational materials for the space as well,” says Aldenderfer, a physics and computer science instructor who’s also an AU alum. “You can buy all the 3-D printers you want, but if no one understands how to design for them, or how to actually use them, then what’s the point?”

Despite that back-to-basics philosophy, Aldenderfer says the makerspace’s technology increases accessibility. While old machine shops often required lengthy apprenticeships, a digital fabrication machine has a much lower barrier to entry.

“You could go into this space, and in three hours, I could have you creating your own digital model of something three dimensional and then printing it out on a 3-D printer,” Aldenderfer says, noting how someone recently printed a giant dragon. “Advances in technology inform aesthetics and inform art here.”

Along with current features, DaBL will soon get a laser cutter, where users can cut through wood or plastic material to create something new. The makerspace has student specialists on duty during open hours, and professors outside AU sciences are using it. Andy Holtin, in the Department of Art, is teaching an Honors course there called Creativity and Innovation.

Ultimately, Aldenderfer believes the STEAM versus STEM debate is a false one. STEM disciplines are about how things work, art is about how things feel, and these concepts are interconnected.

“In biology you’re creating vaccines. In engineering you’re creating gearing systems. In art you’re creating paintings and sculptures,” he says. “All of these disciplines are tied together by the idea of creating, because that’s what humans enjoy.”