A Pre-Med Student’s Reflects on Multicultural Health & Health Equity

Just over two years ago, COVID was seen as the great equalizer. Celebrities, world leaders, and even next-door neighbors were contracting the virus. As a result, the idea of solidarity when tackling COVID was widely disseminated. But in reality, people’s pandemic experiences were not the same or unified at all. Instead, entrenched factors such as socioeconomic status and race shaped a person’s pandemic experience. All in all, the pandemic highlighted health disparities in a way that has never been seen before, and people of color (POC) and at-risk communities were at the forefront.

It’s no secret that POC are more subject to health disparities than their white counterparts. The pandemic has simply highlighted these existing inequities and placed them in the limelight. Think about the single mothers who can’t afford childcare while they get vaccinated, the people of color who can’t trust the US healthcare system because of their historical mistreatment, or the 25 million people in the United States who have a language barrier that prevents them from understanding their doctors’ explanations about coronavirus variants (Connecticut, 2015).

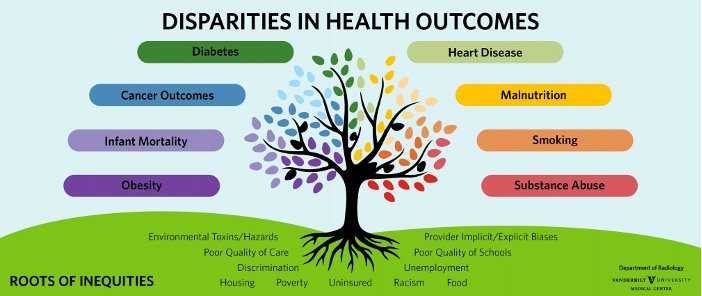

These disparities worsen health outcomes. Along with COVID, POC have disproportionately high rates of HIV, depression, diabetes, heart disease, and more. In response, health professionals are rethinking if the current medical system truly serves all demographics, and how it can be reevaluated to be more equitable for all.

Image credit: Vanderbilt University Medical Center

Image credit: Vanderbilt University Medical Center

So, how do we combat these issues? Understanding health equity — such a vast, complex area of study — might be a daunting task, but learning about multicultural health is a great place to start.

Multicultural health is a term that reflects the need of culturally sensitive, knowledgeable, and non-judgmental healthcare services with respect to people’s health beliefs, behaviors, and practices. This can be achieved through solutions that accommodate the religious, linguistic, and cultural needs of communities.

The university can play a role in expanding our understanding of multicultural health. In fact, there’s an entire course dedicated to it. Multicultural health (HLTH-245), taught by Professor Alexander-Troupe and Professor Callendar in the public health department, offers students a “greater understanding of the social determinants that contribute to health disparities experienced by cultural groups.” I am an aspiring physician, and the class has given my pre-med education a profound sense of context and meaning, deeply impacting my outlook on health.

Discussions in the class covered topics such as cultural competence, implicit bias, racism and colorism, alternative medicine, and health communication. My favorite part was hearing how each of my peers' cultural identities uniquely influenced their perspectives. It was eye-opening to hear personal accounts of acculturation, intersectionality, and medical racism.

Coupled with these impactful discussions were practical skills that are useful in a health-related career. For instance, we wrote a literature review of the National CLAS Standards — a national guide to offering effective and equitable services, which is written for healthcare organizations and providers . By analyzing the standards, I learned both about the importance of health equity and the practical steps needed to get there. For another assignment, we developed public health initiatives to address the health needs of a specific cultural group and created logic models to map its intended outcomes. It made me think critically about addressing health issues at their root cause, which is an essential framework in public health. Additionally, logic models are a standard program planning tool used in public health organizations, business planning, and nonprofits, so learning how to create one is an asset I can carry forward in my career. My favorite assignment was interviewing the program manager of a multicultural health organization of our choice. With this assignment, I witnessed multicultural health in action, almost as if the concepts I learned in class came to life before my eyes.

I left the class not only with a nuanced understanding of multicultural health, but an applied set of skills I can use to make meaningful changes in our healthcare system. Now I have a solid foundation in topics such as health equity, cultural competence, and intersectionality, which will certainly come into play during my pursuit of medicine.

Beyond course offerings, AU addresses health disparities through dialogue, research, scholarships, and more. The Antiracist Research & Policy Center and the Center of Diversity and Inclusion are two campus engagements leading these ongoing discussions. It must be acknowledged that health inequities are woven into the structures that govern our healthcare system, and they cannot be dismantled overnight. However, these initiatives are a robust start in creating a culturally competent and actively antiracist healthcare system.

Pre-meds, public health students, aspiring healthcare professionals — how are we supposed to effectively serve a system without understanding its demographics and inequities? The healthcare system needs to be equipped with practical skills and a comprehensive understanding of multicultural health, and it begins with us. We can eradicate the inequities that disproportionately affect cultural groups and POC. I challenge you to take ownership of your learning experience. Take a public health class, read about multicultural health, and learn about the system you’ll be a part of. The chasm between healthcare systems and the communities they serve is growing wider with time. There has never been a time more primed for change than now.

Works Cited

Alexander-Troupe, S. (2022, January). Multicultural Health Course [PowerPoint Slides]. Department of Public Health, American University.

Connecticut State Department of Public Health. (2015). Individuals with Limited English Proficiency and Literacy. Retrieved from https://portal.ct.gov/DPH/Public-Health-Preparedness/Access-and-Functional-Needs/Individuals-with-Limited-English-Proficiency-and-Literacy

This story was originally written in spring 2022 for AU's Science Writing class.