How AU Aided Refugee Scholars from Nazi Germany

New research by American University graduate students Emma Todd (MA history, concentration in public history ’23) and Benjamin Holt (PhD Western European history ’27) has shed light on an unknown chapter of AU history: the stories of three German scholars with Jewish backgrounds who escaped Nazi Germany in the 1930s and were given safe haven by American University.

Ernst Posner was a professor of archival science (in both Germany and the United States) who held several positions at AU and revolutionized archival administration in the US federal government. Ludwig M. Homberger (former vice president of the German National Railroad Company) became an AU professor and helped rehabilitate the German Transportation system after the war. Fritz Karl Mann (former chair of economics at the University of Cologne) became an AU professor of political economy and chair of the AU Department of Economics from 1936-1954.

Documenting Lives of Those Who Were Saved

Todd and Holt conducted the research for AU’s HIST 412/612 “Germany’s Jews” graduate class, taught by Distinguished Professor of History Michael Brenner, who is AU’s Seymour and Lillian Abensohn Chair in Israel Studies and director of the Meltzer Schwartzberg Center for Israel Studies. The project began when Brenner was researching German-Jewish emigrants in the United States. “It occurred to me to look at the AU archives, and to my surprise I found the records of three refugee scholars AU took in,” he says. “It is a remarkable episode that should be told, and my students did an amazing job in recovering their stories.”

In all, Todd and Holt spent more than three months examining documents from the American University Archives and Special Collections, along with secondary sources such as Ancestry.com. Holt’s paper begins with the origins of German antisemitism and emphasizes the challenges faced by Jewish refugee scholars. Todd’s paper traces the history of immigration immediately before and during WWII, beginning with the 1924 passage of the Johnson-Reed Act, which introduced immigration quotas based on nationality and dramatically impacted European Jews trying to escape the Nazis and immigrate to the United States. Thousands of Jewish refugee scholars sought access to the US, but only hundreds were eventually offered asylum. At the same time, although American universities knew that hiring a refugee scholar could save the scholar’s life, most schools were challenged by lack of funds, antisemitic sentiments, and bureaucratic hurdles at both federal and university levels.

Despite these challenges, Posner, Homberger, and Mann were offered safety and new careers at American University. “AU was still a young and small university in the 1930s,” writes Todd. “This makes it even more surprising that AU hired three refugee scholars in the late 1930s. AU did not have the resources or reach as other major institutions like Harvard and Columbia were able to hire and fight for more refugee scholars due to their prominence and financial ability. AU did not have the endowment that some older private institutions had, and yet were able to organize and secure funds for three new professors.”

Ernst Posner, Archivist on Both Sides of the Atlantic

The American University Archives and Special Collections is home to “about six inches of materials on Poser” including his personnel files and correspondence with colleagues. Holt used these materials plus secondary sources to pull together the story of Posner’s extraordinary life.

Posner was working towards university degrees in history and Germanic languages when his studies were interrupted by the First World War, during which he fought for Germany on both fronts and received two Iron Crosses. After the war ended, he returned to the University of Berlin, earned his PhD, and went on to serve as an instructor at the Institute of Archival Sciences and Advanced Historical Studies, Berlin-Dahlem, as a state archivist for the Privy State Archives of Prussia, and as a collaborator of the Prussian Academy of Sciences. In 1935, the Nuremberg Laws were passed in Germany, and within a few months all professors of Jewish ancestry, including Posner, were forced to resign. After the November Pogrom, around 30,000 prominent Jewish men were arrested and sent to concentration camps, Posner among them.

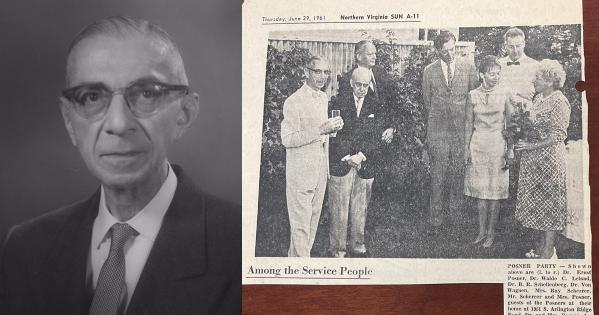

In his paper, Holt documents how Posner’s wife used her influence to get Posner released from the concentration camp: “His wife, Katharine, worked tirelessly for Posner’s release, and eventually succeeded after stressing his war decorations and presenting plans to leave the country to guards.” The Posners, writes Holt, ultimately escaped to the United States. Ernst began work at American University, where he became known as the founding father of academic archival sciences in the United States, creating the first program in American history alongside his good friend, Dr. Solon J. Buck.

“As a result of the psychological trauma that Posner suffered during the Holocaust, he admitted in 1951 that he could never ‘become a Ger[man] civil servant again without breaking my soul,’” Holt writes. “Posner was offered the job as the head of the Bundesarchiv, the German national archives, but declined the offer. This stark admission shows that Posner had both a Jewish consciousness and no intention of ever relocating back to his country of birth. Ernst Posner is an example of a Jewish refugee scholar who had an unimaginably large impact on his field and those in his life.”

Ludwig Homberger

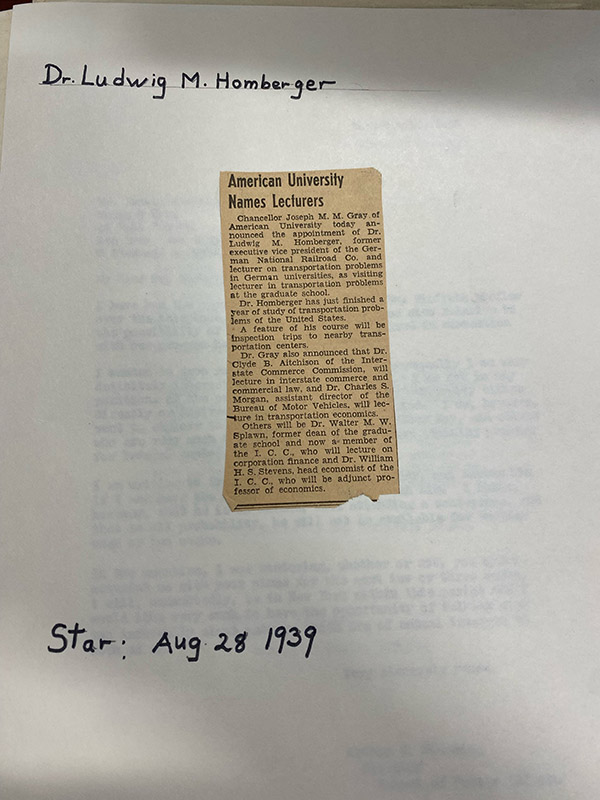

Todd focused her research on Ludwig Homberger, born in Germany in 1882 to Jewish parents. There is very little written about Homberger’s life, but Todd pieced together his story by using material from the American University Archive, along with immigration documents. Homberger’s immigration documents show that Homberger married “a Miss Wagner, an Aryan German, and daughter of a Lutheran minister” in 1913. Interestingly, the document also notes that “Dr. Homberger became a Protestant” after his marriage.

Homberger went on to become a successful German National Railroad executive, completely reorganizing and revamping the railroad’s finances, Todd writes. He was so valuable to the railroad that several prominent Nazis pushed to keep him working there even after Jews were forced to retire from similar positions. But ultimately, Homberger was forced to step down, despite his support and despite the fact that he had converted to Protestantism.

His road to American University, filled with back-and-forth letters and negotiations and visa and funding challenges, was not an easy one. But in 1939, Arthur Flemming, director of AU’s School of Public Affairs at American University, officially offered Homberger a position as a lecturer at AU with financial assistance from the Rockefeller Foundation and the Oberlaender Trust.

Homberger held many titles during his tenure at AU, and from 1945-46, he took a leave of absence to return to Germany at the request of the US government and the new German government to survey and help rehabilitate the German Transportation system, Todd writes. Homberger reported his findings to both governments. In 1946, he returned to American University as a professor of transportation. From 1948-53 he was the director of the Division of Professional Institutes, and in 1953 he retired as a professor emeritus.

In her conclusion, Todd writes about Homberger’s contributions to his scholarly field, but also about American University living up to its ideals. “Homberger is an example of a scholar who made an impact because he was lucky enough to escape the Nazi regime. AU was also an example of a progressive university dedicated to internationalism and fostering interdisciplinary studies despite its size and youth.”