Audrey Payne, SOC/MA ’12

It’s easy to forget that we are part of nature—not separate from it. I am reminded of that as I hike the Appalachian Trail from Georgia to Maine this summer. I’ve already hiked 800 miles through East Coast wilderness and have forgone many modern conveniences in order to return to a more primal state. And it has been one of the best decisions of my life.

We are barraged by a ridiculous amount of information: 24-hour news, social media, advertisements. It’s exhausting and it’s making us depressed. But studies have shown that even a short walk in the woods can lower stress levels significantly.

The difference I see within myself since beginning my journey in March has been profound. I’m more confident, patient, open-hearted, and happy. I feel more alive and awake than I have in years. Many of the people I’ve met along the trail are among the kindest and happiest that I know, and I believe exposure to nature plays a significant role in that.

My recommendation? Get outside this summer. Take a hike with a friend, go kayaking, read a book under a tree. Your mind—and body—will thank you.

Follow Payne’s journey at thetrek.co.

Paul Wapner, SIS Professor

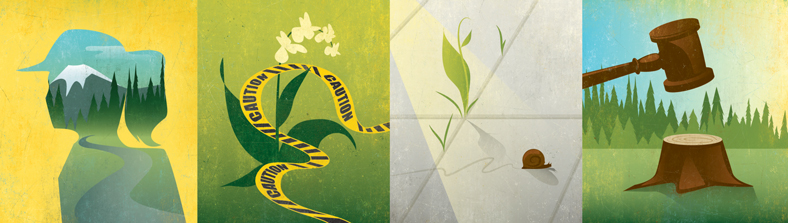

Environmentalists have always worked to protect nature. They have long expressed a love of mountains, rivers, orchids, and redwoods, and fought on behalf of the more-than-human world. But over the past century, people have so tamed, colonized, and contaminated the natural world that safeguarding it from humans is no longer an option. The human signature now imprints itself everywhere. Indeed, our impact is so extensive that we now live in a new geological era, the Anthropocene—the Age of Humans.

The “end of nature” challenges the environmental movement to find new objects of devotion. Without nature, what should environmentalists think and care about? How should they act politically? What is their raison d’être? As the Anthropocene deepens, environmentalists have been asking these questions and arriving at insightful answers. For instance, environmentalists now recognize the intersectionality of environmental harm and other injustices; they also see how every human action need not be a blight on the Earth, but can contribute to biodiversity, ecological exuberance, and planetary well-being. Environmentalists are growing new identities in the Anthropocene. Environmentalism is very much alive after nature.

Wapner teaches global environmental politics.

Sara Ghebremichael, SPA/MPA ’13

I believe nature is the source and the surrounding for all of life—that green and brown stuff that calms our senses and brings them into focus. I remember as a child being so much closer to the ground and being aware of the pavement and the grass growing through it. I knew every sight and smell, every crack and snail trail.

Nature is the only thing complex enough to keep young minds engaged. In my work at City Kids Wilderness Project, which provides enriching and challenging outdoor experiences for DC youth, I encounter brilliant young people hungry to be stretched in positive ways, to have their intellect nurtured, to build bonds with one another, and to test their physical limits in nature.

A friend of mine posts photos to a series called “concrete plants,” where she shows incredible bits of plant life that have worked their way through a built environment that attempts to suppress them. I see City Kids participants this way: resilient in the face of life’s challenges, sprouts of life finding a way.

Ghebremichael is director of administration and special projects at City Kids Wilderness Project.

Shane Levy, Graduate Gateway Program, ’11

One of my formative experiences growing up was climbing Mt. Katahdin in Maine’s North Woods. I vividly remember trekking through pristine nature and peering out at the summit, across a sea of rolling peaks dotting Maine’s landscape.

It was clear to me then, just as it is now, that these public lands belong to all of us. They are part of our country’s history, culture, and economy. And we must conserve them to ensure they’re part of our future.

In one of President Obama’s final acts, he proclaimed the land just east of Mt. Katahdin as the new Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument, guaranteeing public access and protecting 87,000 acres from destructive practices. However, just two years later, our country’s parks and public lands—including Katahdin Woods and Waters—face unprecedented threats from an administration determined to roll back safeguards for people, places, and wildlife.

We have a responsibility to forge a more inclusive outdoor legacy and to not sacrifice these special places in nature. Now more than ever, we need to rebalance the scales of development and conservation so that everyone can enjoy access to nature for generations to come.

Levy is communications manager for the Sierra Club’s Ready For 100 campaign.