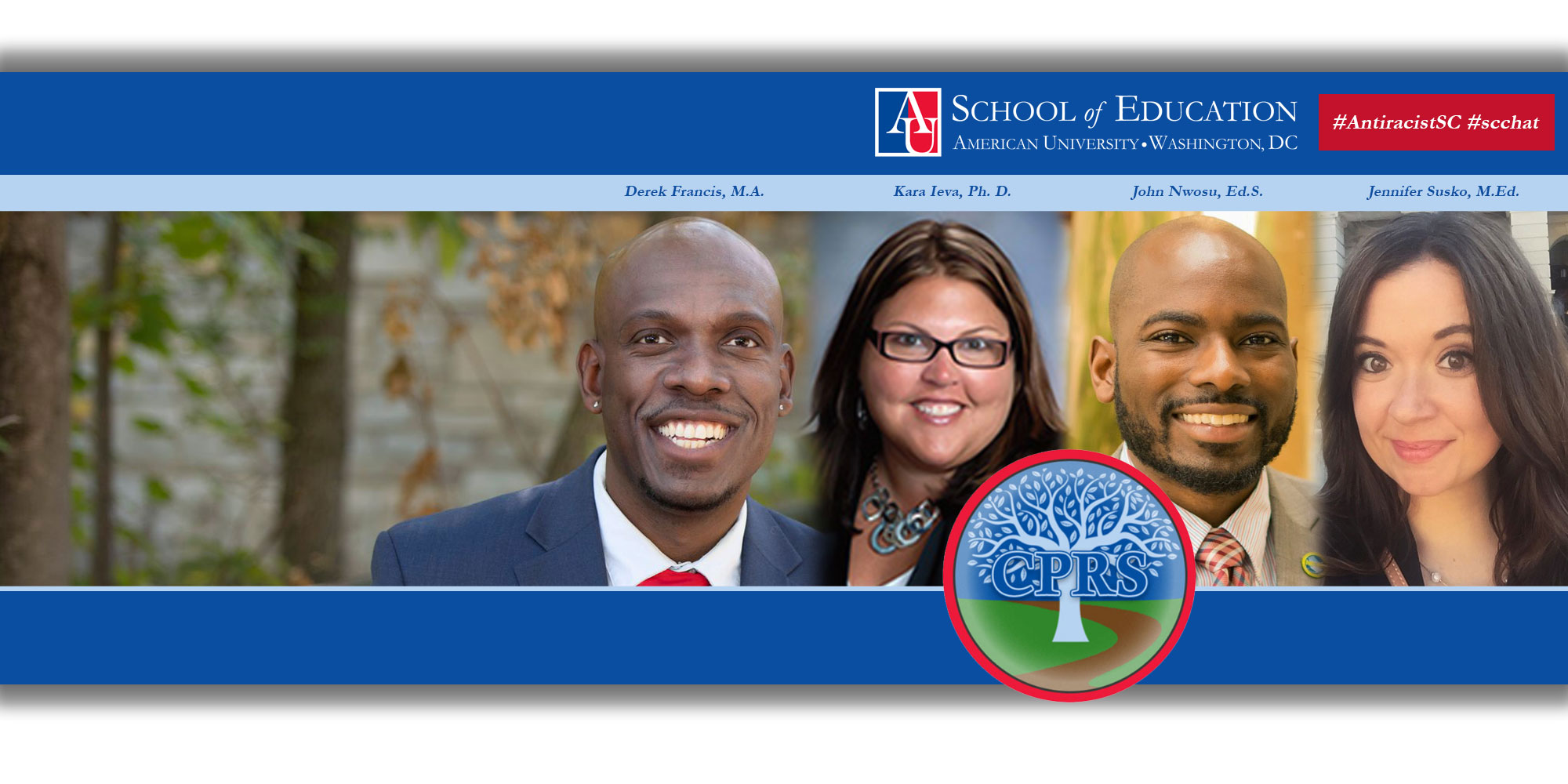

Antiracist School Counseling: A Call to Action

The Center for Postsecondary Readiness and Success is dedicated to partnering with school counselors, counselor educators, college advisors, and any career/college advisors to increase institutional responsibility for improving postsecondary outcomes through the use of counseling, advising, mentoring, and/or coaching. Through its efforts, the Center strives to advance antiracist school counseling and college/career advising practices, pedagogy and policies.

School counselors recognize and affirm the wholeness and humanness of students, families, and their communities through their work with students and the systems in which they learn and develop. Yet, many school counselors recognize that schools continue to operate in ways that harm Black and Brown students, thereby calling for a change in the profession to not only create antiracist school settings, but also to eradicate anti-blackness in the school counseling profession.

What does an antiracist school counselor do differently?

What does an antiracist school counselor do differently?  How would you define antiracism?

How would you define antiracism?