To the Point: Why Is Michelangelo’s "David" Controversial?

To the Point provides insights from AU faculty experts on timely questions covering current events, politics, business, culture, science, health, sports, and more. Each week we ask one professor just one critical question about what’s on our minds.

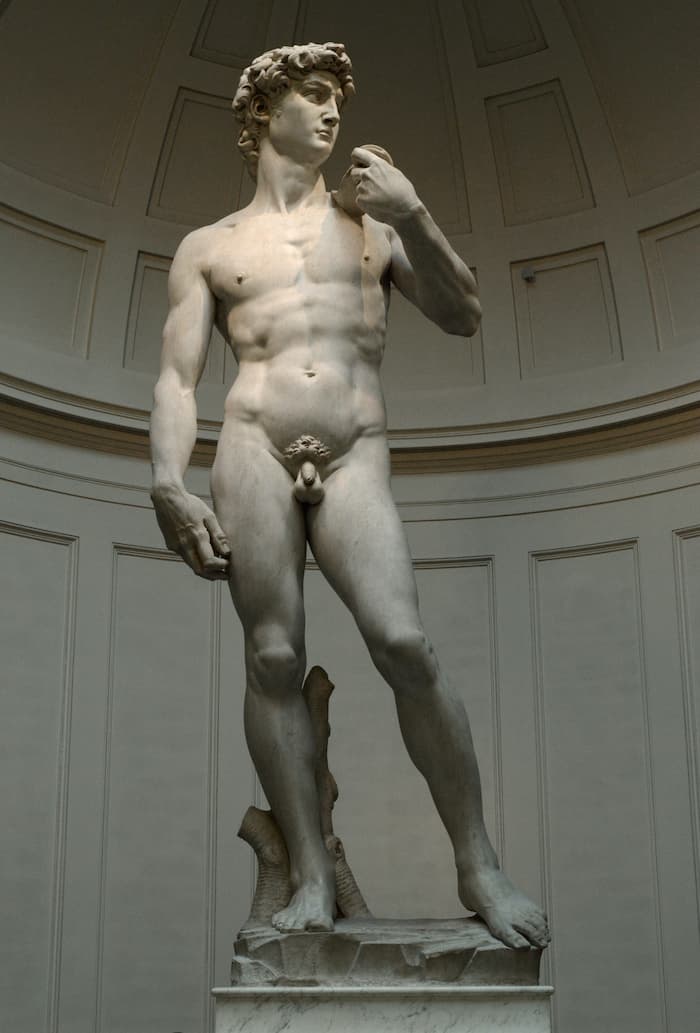

In March, a Florida principal resigned after a photo of Michelangelo’s sculpture David was shown in a sixth-grade art history class at a Christian charter school in Florida. Some parents complained that the work was too pornographic to be shown to children, and that they were not given the opportunity to refuse their children’s participation in the lesson. The school’s board told the principal to either resign or be fired. A famous Renaissance marble sculpture, the 17-foot-tall David depicts the biblical figure just prior to slaying Goliath. Created between 1501 and 1504 in Florence, Italy, David is seen by over 1.4 million visitors annually at the Galleria dell'Accademia.

Given the importance of the work in art history and its depiction of a biblical subject, we asked professor and art historian Kim Butler Wingfield why David's nudity is so controversial:

Concerns about David's full nudity are not new. A document published in 2000 revealed that a metal garland covering for David was commissioned in 1504, the year the sculpture was completed, and replaced with a new one in 1508, which we know was gilded.

Michelangelo was competing with the idealized heroic nude male bodies in ancient Greco-Roman sculptures, together with ancient literary descriptions of colossi, but the David had important religious significance as well. Michelangelo likely intended the nudity of his idealized body to symbolize the prophet's state of grace and elevated humanity; after all, his fleshly lineage was Mary's and Christ's. This religious signification was appropriate to its original planned location on top of a buttress of the Florentine cathedral dedicated to Mary. It was also consistent with the currency of Incarnationist theology, glorifying the moment Christ assumed perfected human flesh, in the period, which spurred an interest in representing ideally beautiful bodies—sometimes nude—in sacred contexts.

This was evidently at odds with more conservative elements in Florentine society. The Medici had been expelled from Florence in 1494, after which the radical Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola assumed control. Holding deeply conservative views, he rejected the all’antica cultural renewal sponsored by the Medici, which he characterized as sinful and corrupting. Although Savonarola was executed in 1498, he retained an ardent following who perpetuated a strain of cultural conservatism that lingered well after his death. Public displays of genitalia in art were eschewed—hence the modification. A contributing factor may have been a shift in meaning, from religious to more emphatically political, when its location was changed to the front of the civic palace. The site shift enabled viewers to engage with the sculpture more directly; no longer 80 meters above ground level as designed, the exposed genitals may have been deemed too proximate. At any rate, this debate is rooted in history, even if the politics of the current day are distinct. I would characterize it as progressive vs. conservative religious views in the Renaissance, and secular views on art vs. conservative religious views today.

The Florida controversy revives a religious conservatism about art similar to that with which Michelangelo had to contend. Perhaps a better understanding of the original theological rationale for the sculpture’s nudity—reflecting the sincere belief that bodies were divinely created in God’s image—would ameliorate concerns and mitigate accusations of “pornography.” The larger debate about parental rights concerning the material educators choose to show their children at school is a complicated, and unfortunately highly politicized, one. A fuller historical understanding of Michelangelo’s objectives in the David could prompt fewer parents to “opt out.”

About Professor Butler Wingfield

Professor Butler Wingfield (PhD with distinction Johns Hopkins University, BA with honors Harvard University) is Associate Professor of Renaissance and Baroque Art History in the Art Department at American University. She researches humanism and efforts to reconcile all’antica and sacred culture in Italian Renaissance art. She has special expertise on the High Renaissance, having published a number of studies on topics including: the Madonna images of Raphael and Michelangelo, the Vatican “Rooms,” and the Sistine Chapel.