Research

Oral History and Homelessness

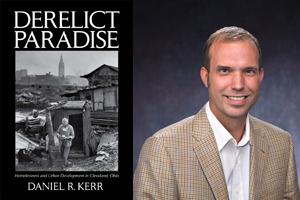

Professor Daniel Kerr has spent two decades uncovering American homelessness. The history professor, who joined AU’s faculty this fall from James Madison University, has turned to oral history to gain a greater understanding of the underlying circumstances surrounding homelessness in America and to give a voice to the homeless. This dedication has manifested itself in Kerr’s new book, Derelict Paradise: Homelessness and Urban Development in Cleveland, Ohio.

Kerr, who grew up in the Cleveland suburbs, remembers witnessing poverty as a child in his very own city. “We would drive down this street lined with mansions as we drove downtown,” says Kerr, “and then all of a sudden, we’d be in a completely different part of town.,” Kerr recounts the neighborhood differences he noticed as he would drive from the wealthier suburbs to the more impoverished neighborhoods in Cleveland where he observed many people living on the streets or in less than ideal conditions. “The hardest thing to believe as a child,” says Kerr, “was that these neighborhoods were in the same city. They weren’t even all that far from each other.”

These experiences sparked Kerr’s interest in helping to alleviate issues of homelessness, and in the summer of 1993, after completing his undergraduate work at Carleton College, he moved to New York City to join the squatters movement. “After college, I was really running away from academia,” says Kerr. “I was looking to do something that would make a tangible impact.”

Shortly after he arrived, Rudy Giuliani became mayor and escalated the city’s efforts to evict the homeless and the squatters as a part of his “quality of life” initiative. Kerr moved into a squat, helped run a free kitchen, did street theater, and organized to prevent evictions. In May 1995, he and other squatters barricaded 13th Street to prevent the eviction of five buildings. For a short time, the squatters held off thousands of riot police who were armed with helicopters, snipers, and a tank. “As I lived in the squats, I started to understand the power of storytelling,” says Kerr. “People would sit around at night and tell stories, and I began to wonder how these stories, and oral history in general, could be used to build social movements.”

That fall, Kerr moved back home to Cleveland to pursue graduate work at Case Western Reserve University. He began to take an even closer look at the problems of homelessness occurring in his own hometown. Kerr organized a free weekly picnic on Public Square, a central plaza in downtown Cleveland, where he set up a video camera and television and invited homeless community members to share their own stories. “We created a space in Cleveland where people could talk, define issues in their own lives and in society, understand the complexities of these issues, and move forward,” says Kerr. “We invited people to tell us their understanding of the history and causes of homelessness.”

Throughout this process, Kerr interviewed nearly 200 homeless Clevelanders and showed videos of many of these interviews at shelters and community centers throughout Cleveland. “People were able to hear each other’s stories and analyze them,” says Kerr. “We were able to look at these people’s stories and ask why homelessness had become such an entrenched part of life in Cleveland.”

As Kerr continued his work of understanding homelessness as a modern issue, he began to look into homelessness in its historical context. “I wanted to understand how homelessness became something that was expected,” says Kerr. “How did it become a way of life?”

Kerr spent the next several years combing through local archives and continuing to talk to homeless individuals. As his research progressed, the picture of homelessness in Cleveland and in America became clearer. He identified the roots of the modern shelter system in the period that followed the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. The shelter played a clear role containing and monitoring the city’s homeless – the population blamed for prompting the disorder. While the shelter receded in importance following World War II, it reemerged as a key institution in the 1980s when wages melted down and people could not access housing, and urban leaders sought to contain and control the people sleeping on the streets as they promoted Cleveland’s renaissance.

Kerr says he hopes Derelict Paradise will show that “homelessness has deep roots in the shifting ground of urban labor markets, social policy, downtown development, the criminal justice system, and corporate power, rather than being attributable to the illnesses and inadequacies of the unhoused themselves.” Derelict Paradise is the first book in Kerr’s two-book series. Kerr plans to release a second book about the practice of oral history based on his experiences with Cleveland’s homeless.

“The problems I observed in Cleveland are problems that exist around the country,” says Kerr. “Understanding the history of homelessness can help us figure out how to change this part of our society on a systematic level and move forward.”