Research

Curious Minds: Perry Zurn is a Scholar and Proponent of Curiosity Studies

College campuses are like laboratories of intellectual curiosity. But if you think curiosity—or the desire to know—is a fixture of university curriculums, you would be wrong. While curiosity feeds into every academic subject, there’s been surprisingly little study of curiosity itself.

Curious college professors abound, so perhaps it just seemed a little too obvious? “This is like when you’re in the water, you don’t ask, ‘What is water?’ That’s precisely what’s happening here with curiosity,” says American University’s Perry Zurn. “People just assume they are being curious, and they know what it is. But they don’t.”

Zurn is trying to give curiosity the extensive treatment it deserves. He currently has three books on the subject in development: He’s a primary editor for an upcoming book titled Curiosity Studies; Zurn is working with his twin sister, University of Pennsylvania neuroscientist Danielle Bassett, on Curious Minds, which will look at the philosophy and neuroscience of education; and he’s writing a timely book called The Politics of Curiosity.

Zurn is an assistant professor of philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences.

Politics and Resistance

The Politics of Curiosity will examine how political commitments inform the questions we think are worth asking. Zurn believes this points to fundamental divisions in the country. He says that no political party or ideological cohort has a monopoly on curiosity; people just happen to be curious about different things.

“Liberals only see their kind of content, and they get curious about that. And conservatives only see their own content, and they’re curious about that. We need to start practicing the kind of curiosity that doesn’t just extend my current interests, but rather that opens me up to changing my current interests. I think that’s the only way we’ll be able to talk across these differences today,” Zurn says.

He will explore the role of curiosity in political protest. These ideas almost echo a George Bernard Shaw line, famously deployed by the Kennedy brothers: “You see things; you say, ‘Why?’ But I dream of things that never were, and ask ‘Why not?’”

Zurn explains, “Especially after Barack Obama, we think a lot about hope as being one of those things that fuels political resistance movements. But I’d argue curiosity is another really important one. It’s people asking, ‘How can we do things differently? What would it look like if we did?’”

Academic Passion and Neuro-Diverse Learners

The curiosity debate is particularly relevant to education. He says people who study this issue feel that the K-12 educational system is stifling curiosity among kids. Zurn worries that by the time students reach college, they’re prioritizing “job interests” over searching for their true academic passion. He also says taking courses outside of your major, and exploring a wider array of subjects, can bolster a student’s career growth.

“Our world is changing so fast. We can’t prepare someone this year to do the things that are going to be necessary in five years. So, we need to give them the skills that enable them to show up for those new challenges five years from now,” Zurn says. “And curiosity has got to be one of those skills.”

In everyday parlance, people are often described as naturally curious, while others are disparaged for their lack of curiosity. Zurn says it’s unclear how much you can label someone inherently curious or incurious. But he says studies of curiosity and education have, to their detriment, focused too much on conventional learners.

“They don’t look at students with learning differences, learning difficulties, or neuro-diverse students. There’s a whole realm of erasing the curiosity of people who don’t learn in an expected fashion,” Zurn explains. “I want to push against that and say, ‘You can’t just assume students with learning differences aren’t curious.’”

And while people generally aspire to be curious, Zurn argues that curiosity isn’t always beneficial for society. European colonizers collected indigenous artifacts as trophies, often bringing them back to celebrate as “curiosities.” And there’s the sometimes-exploitative history of circus “freak shows,” where spectators paid to see people deemed unusual or odd.

Encouraging Student Curiosity

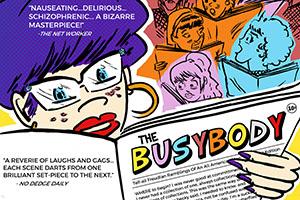

For his curiosity work, Zurn has gotten significant student participation. He’s worked with graduate student Stephen Masson on analyzing and identifying major practices of curiosity. One is the “Busybody,” for those who constantly scroll news feeds or Facebook; the second is the “Hunter,” with a college professor-like focus on learning something deep and specific; and the third is the “Dancer,” showing creative and imaginative curiosity. An artist Zurn met painted images based on these three practices, and Masson now believes they’re close to identifying a fourth type of curiosity.

Caroline Kish, an undergraduate double majoring in philosophy and American studies, got to know Zurn from his western philosophy class. Zurn has worked with Choose to be Curious podcaster Lynn Borton, and Zurn helped Kish secure an internship with Borton’s podcast this semester.

In preparation for podcast episodes, Kish does extensive research about each guest’s work. “The greatest thing I’m getting out of this internship is experiencing and listening to these different perspectives relating to curiosity. I was able to meet with the Arlington County board chair one week, and then a neuroscientist the next week. And they’re related through their interest in curiosity,” she says. “I think by learning more about curiosity in other people’s lives, it really is teaching me how to stay curious throughout my life.”

A podcasting internship was an unexpected turn for Kish, who plans to attend law school after graduation. But, like Zurn, she also believes that engaging with different mediums and ideas will help her long-term educational development. And she already feels indebted to Zurn and other professor-mentors on campus.

“Professor Zurn is always willing to help me with any questions I might have. I have gone to his office hours to talk about a different philosophy class,” Kish says. “He’s incredible.”

The Choose to be Curious podcast will also be a digital platform for the Zurn-edited Curiosity Studies, as authors/contributors to that book will soon appear on Borton’s show.

What the Future Holds

Zurn himself first started reading philosophy in high school. While seriously pursuing this work, he noticed that few people were studying curiosity—there wasn’t even a philosophy-based book on the subject until 2011.

He’s now excited to be promoting curiosity as an interdisciplinary field. He says neuroscientific breakthroughs could lead to a greater understanding of it, and like learning itself, there will be discoveries no one can foresee.

“With what’s happened in the 30-some-odd years I’ve been alive, I just think about what another 30 years will bring,” he says. “If curiosity is anything, it will lead us beyond what’s recognizable to ourselves and to the world.”